Eyewitnesses

Olha Vakalo: An experienced journalist, Olha reflects on her life under Soviet rule and her engagement in youth movements from [year] to [year]. Her narrative intertwines personal experiences with the national transition, highlighting the mixed emotions brought by Gorbachev’s reforms and the challenging shift from a Soviet to an independent Ukrainian identity.

Olha began her career as a kindergarten teacher, idealizing everything associated with communism, especially Lenin. However, as the party’s direction shifted, new winds blew into her hometown of Zaporizhzhia, prompting her journey of self-realization. Her experience as a schoolgirl, for whom the Ukrainian language was an optional subject that could be dropped to avoid additional study, is particularly interesting. Despite this, her parents insisted that she learn it, fostering a resistance to cultural colonization.

This resistance and her subsequent re-evaluation of her identity in adulthood ultimately paved the way for Olha to become a well-known journalist in her town. Through her reporting, she explored and highlighted the complexities faced by individuals amidst social challenges. Interestingly, through her process of self-awareness and professional development, Olha transformed from being a small cog in the system to an influential individual with freedoms and rights, making significant contributions to her community’s decolonization discourse.

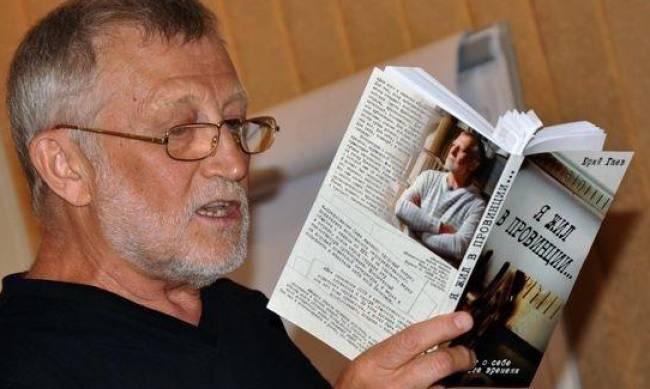

Yuriy Haiev: As a journalist and author from Zaporizhzhia, Yuriy provides a unique perspective on the media landscape during and after the Soviet era. His accounts offer insights into the challenges of working under a repressive regime and the transformative societal shifts during perestroika. His experiences during significant political movements, like the Maidan protests, underscore the evolving dynamics of Ukraine’s political and media environments.

Yuriy is a veteran journalist with 40 years of experience, including working under the challenging conditions of the Soviet era. During that time, he faced significant restrictions, explaining, “We were forced to find the good where it did not exist and to find faults where it suited the authorities. All materials had to pass through strict censorship before publication.” Yuriy’s work also involved interactions with the KGB, adding another layer of complexity to his journalism career. He kept a personal journal detailing his emotions and impressions of the journalistic climate and reality of those times. After the Soviet regime, Yuriy published a book titled “I Lived in the Province,” which he developed over ten years. In this book, he shares his uncensored experiences and insights. For him, freedom of speech in journalism is essential for democracy, as it allows for the unimpeded flow of information and holds power accountable, ensuring a well-informed public.

Iryna Podolyak: Serving as a former First Deputy Minister of Culture, Youth, and Sports, Iryna Podolyak played a pivotal role in Ukraine’s cultural and political spheres, especially from 2014 to 2020. Her legislative work significantly shaped the cultural policies of post-Soviet Ukraine, promoting the Ukrainian language and modernizing cultural institutions. In her discussions, Iryna emphasized the critical transitions from Soviet influence to a rejuvenated national identity, illustrating the complexities of Ukraine’s evolution in governance and cultural autonomy.

Iryna’s experience illustrates the profound impact that cultural engagement can have on democratic processes. By participating in cultural initiatives that revived and celebrated Ukrainian heritage, she and others like her played a crucial role in fostering a sense of national identity and unity. This strengthened collective identity was vital for mobilizing the public, especially the youth, towards democratic ideals and participation. Her story underscores how cultural resurgence can act as a catalyst for political awareness and action, culminating in significant democratic milestones such as Ukraine’s 1991 independence referendum. Thus, Iryna’s experiences from the 1980s not only enriched her personally but also contributed to shaping the democratic landscape of Ukraine.

Pavlo Gudimov, born on October 12, 1973, in Lviv, Ukraine, is a multifaceted musician, former guitarist of the renowned band “Okean Elzy,” and an art manager. After studying at the Ukrainian State Forestry University, he pursued a music career starting in 1991. Gudimov founded the band “Gudimov” and later established a cultural holding that includes an art gallery, an architectural workshop, and a publishing house. He has been actively involved in curating Ukrainian and international art projects.

During Ukraine’s transition period, Pavlo Gudimov played a pivotal role through his artistic and cultural contributions. He was involved in founding several artistic and cultural initiatives, including an art gallery and an architectural workshop. His efforts helped foster a vibrant art scene in Ukraine, supporting the country’s cultural resurgence during a time of significant political and social change. Gudimov’s work in the arts has been integral in promoting Ukrainian identity and heritage both nationally and internationally.

Tasks

Task 1 Olha Vakalo

Topic: The evolution of Belarus’ youth movement in the 1980s: From cultural and educational to political

Duration: 45 minutes

Materials:

- Computer and projector for displaying digital content;

- Internet access for viewing an interview excerpt;

- Markers and sheets of paper for group work.

Audience: High school students.

Objective:

To explore the personal experiences of Olha Vakalo, a Zaporizhzhia journalist and civil activist, during Ukraine’s transition from the Soviet Union to an independent state. The task will examine how personal narratives reflect and influence broader societal changes related to democratization and decolonization.

Task Outline

1. Introduction (5 minutes)

Introduce the context of the interview with Olha Vakalo, focusing on her experiences during the late Soviet period and the early years of Ukraine’s independence.

Explain the concepts of democratization and decolonization, particularly how personal experiences during transitional periods can illuminate broader societal changes.

2.Video (10 minutes)

Show an excerpt from the interview with Olha Vakalo discussing her life and the societal atmosphere during the late 1980s and early 1990s in Ukraine (suggested clip: from the beginning to 5:33).

Students should focus on her reflections on the changing political landscape and her emotional responses to these changes.

3.Group Discussion (10 minutes)

Divide the students into small groups.

Ask each group to discuss how Olha’s personal experiences reflect broader processes of democratization and decolonization in Ukraine. Questions for consideration include:

How do Olha’s experiences during the Soviet era and her initial fears about independence reflect the challenges of decolonization?

How does Olha’s change in perspective over time illustrate the process of democratization?

4. Group Presentation and Class Discussion (15 minutes)

Have each group present their analysis of how individual narratives like Olha’s can shed light on societal transformations.

Facilitate a class discussion to draw parallels between personal and national transformations, exploring how individual stories contribute to our understanding of historical events.

5. Reflection and Critical Thinking (5 minutes)

Encourage students to reflect on the following questions:

How do personal stories enhance our understanding of historical events like the fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of independent nations?

What role do individual citizens play in the processes of democratization and decolonization?

6. Conclusion (5 minutes)

Summarize the key insights discussed in the class regarding the interplay between personal experiences and broad societal changes.

Highlight the importance of personal narratives in understanding and teaching history, particularly in contexts of political and cultural transitions.

Supplementary quote from the interview with Olha Vakalo to facilitate student discussion:

“I was forced to live in the Soviet space, where deception and fear were constantly felt. One day, we realized that Ukraine exists, and it seemed that everything that had come before had nothing to do with us. These events made me believe that we were the chosen ones, extraordinarily fortunate, as previous generations had to endure a rotten, insincere, and terrible Union. Finally, we felt the mustiness of lies and mothballs, and now everything will change — there will be a new Soviet era with a human face.”

Extra questions with visual material:

Picture 1. Lenin in childhood.

How did Olha change her mind about a Lenin statue in kindergarten? How does propaganda work with emotions in Olha’s example?

Task 2 Yuriy Haiev

Objectives:

- Understand the personal experiences of individuals during significant historical periods in Ukraine.

- Learn about the role of journalism and media under Soviet rule and during the transition to independence.

- Discuss the impact of historical changes on personal identities and societal structures.

Materials:

- Video interview with Yuriy Haiev;

- Projector or smartboard to show video content;

- Handouts with key excerpts from the interview for reference;

- Discussion questions prepared in advance.

Lesson Duration: 45 minutes

Lesson Procedure:

Introduction (5 minutes)

- Begin with a brief introduction of Yuriy Haiev, highlighting his background as a journalist during the Soviet era and his witness to Ukraine’s transition to independence.

- Explain the importance of personal testimonies in understanding history.

Video Viewing (15 minutes)

- Show selected clips from Yuriy Haiev’s interview where he discusses:

- His experience as a journalist in Soviet Ukraine;

- His observations of societal changes during Perestroika and Ukraine’s move toward independence;

- His personal transformation and acceptance of Ukrainian independence.

Class Discussion (15 minutes)

- Discuss the video using guided questions:

- How did the historical events Yuriy describes compare to official historical narratives?

- What challenges did journalists face in the Soviet era when trying to report truthfully?

- How did Yuriy’s personal identity and perceptions change with Ukraine’s transition?

- What can we learn about the power of media and information from Yuriy’s experiences?

- What did you learn from Yuriy’s story about life in the Soviet Union?

Group Activity (5 minutes)

- Divide students into small groups and have them list ways in which personal histories like Yuriy’s can contribute to our understanding of national histories. Each group shares their list with the class.

Wrap-up and Homework (5 minutes)

- Summarize the key points discussed in class.

- For homework, assign students to write a short essay on how individual stories like Yuriy’s can influence our understanding of historical events, using examples from the interview.

Supplementary quote from the interview with Yuriy Haiev to facilitate student discussion:

“I once told them I knew I wanted to end our relationship. He understood everything clearly, and that was the end of it, because those were my dealings with the KGB. But this is my experience, you understand? My personal experience, and I don’t see it as a mistake. In a similar transformation, as I began reading more Ukrainian books, I felt a profound shift in my identity. My perspective changed so deeply that I named my mindset ‘My Ukraine.’ This change wasn’t just about the place where I live; it was a shift in my mental framework. Reflecting on this, I realized I had become Ukrainian not merely by geography but through a fundamental change in my consciousness, like the character Rozov in the book I wrote.”

Task 3 Iryna Podolyak

Cultural renaissance as a catalyst for decolonization and democratization in Ukraine

Duration: 45 minutes

Materials:

- Computer and projector for displaying digital content

- Internet access for viewing an interview excerpt

- Markers and sheets of paper for group work

Audience: High school students (age 14-17)

Objective:

To explore the dual role of cultural renaissance in both the decolonization process and the democratization efforts in Ukraine, using the personal and professional experiences of Iryna Podolyak during the country’s transitional period as a case study.

Task Outline

- Introduction (5 minutes)

- Introduce Iryna Podolyak, highlighting her roles in cultural development and legislative work during Ukraine’s transition from Soviet rule.

- Define decolonization and democratization, emphasizing how cultural renaissance interlinks both processes by fostering national identity and supporting democratic governance.

- Video (10 minutes)

- Show an excerpt from the interview with Iryna Podolyak focusing on her participation in cultural and political reforms during the late 1980s and early 1990s (suggested clip: 2:15 – 5:30).

- Instruct students to note how Podolyak describes the impact of cultural movements on public engagement and political changes.

- Group Discussion (10 minutes)

- Divide students into small groups.

- Assign each group to discuss the influence of cultural renaissance on both decolonizing Ukraine from Soviet legacies and laying the groundwork for democratic practices. Encourage them to consider how cultural initiatives can empower individuals and mobilize them towards political participation and advocacy.

- Group Presentation and Class Discussion (15 minutes)

- Have each group present their findings on how cultural renaissance has contributed to decolonization and democratization in Ukraine.

- Lead a class discussion to compare these findings, exploring the effectiveness and limits of cultural movements in changing political and social landscapes.

- Reflection and Critical Thinking (5 minutes)

- Ask students to reflect on the following questions:

- Can cultural renaissance alone drive significant political change? Why or why not?

- What other elements are necessary to ensure that cultural movements contribute effectively to democratization and decolonization?

- Ask students to reflect on the following questions:

- Conclusion (5 minutes)

- Recap the key insights discussed in the class regarding the interplay between culture, decolonization, and democratization.

- Emphasize the importance of cultural identity and heritage in shaping democratic societies and breaking away from colonial legacies.

Supplementary quote from the interview with Iryna Podolyak to facilitate student discussion:

“We’re generally not trained to discuss things, and this is a remnant of the Soviet period. We haven’t discussed the 1930s, we haven’t discussed 1918-1920; in our narrative, people are either heroes or criminals. Even our public space, how and to whom we erect monuments — it’s not about discussion, it’s about indoctrination. We have time to establish a process of remembrance, but I’m not sure we have the people for it.

I thought my generation, the generation that was 20 in the 1990s, would turn the world upside down. But it seems we blew it in both the 1990s and the 2000s. Although I was never indifferent and did everything that depended on me.”

Extra task about the Chervona Ruta festival, based on Iryna’s story.

Use the words of Sister Vika from the Chervona Ruta’89 festival and ask the students to answer the following questions.

The original song at the event https://youtu.be/M43TqqBUDLQ?si=RGQCMuDLmjM47h68

Sestrychka Vika, real name Viktoria Vradiy, gained fame by winning the first “Chervona Ruta” festival in 1989, captivating audiences with her rock and electronic music. After the festival, she released several albums and went to the USA in 1993 to continue her music career. Vika worked in US music clubs, got married three times, and briefly returned to Ukraine in 2004. Currently, she resides in California, working as a manager. You can find more detailed information about her journey here.

Song lyrics:

How does the song reflect the challenges of national identity and cultural transition in Ukraine?

- What emotions does the song convey about Ukraine’s transformation after the Soviet era?

- The lyrics mention “shame,” “forgotten language,” and “youth shouting ‘hurrah’”—what do these phrases suggest about the impact of Soviet influence on Ukrainian identity?

- The chorus states: “Who does not live, does not die; Who does not open their eyes, sees nothing.” What do you think this means in the context of political and social awakening?

- How does the mention of language (kovbasa vs. kolbasa) highlight cultural and historical tensions in Ukraine?

- The song refers to Morozenko — a historical Cossack figure. Why do you think the songwriter uses this symbol, and how does it connect to Ukraine’s search for identity during its transition?

- Based on this song, do you think transition is more about breaking from the past or preserving cultural memory? Why?

This discussion will help students analyze personal and collective struggles in a transitioning society and connect them to broader historical shifts in Ukraine.

Task 4 Pavlo Gudimov

Art, Music, and Political Resistance in Ukraine’s Transition

Duration: 45 minutes

Materials:

- Computer and projector for displaying digital content;

- Internet access for viewing an interview excerpt;

- Handouts with key excerpts from the interview for reference.

Objective:

To explore the role of art and music in political resistance and societal change, using Pavlo Gudimov’s experiences with the Vyvykh Festival, Ukrainian rock music, and cultural independence.

Task Outline:

- Introduction (5 minutes)

- Discuss how art and music can serve as forms of protest and identity-building.

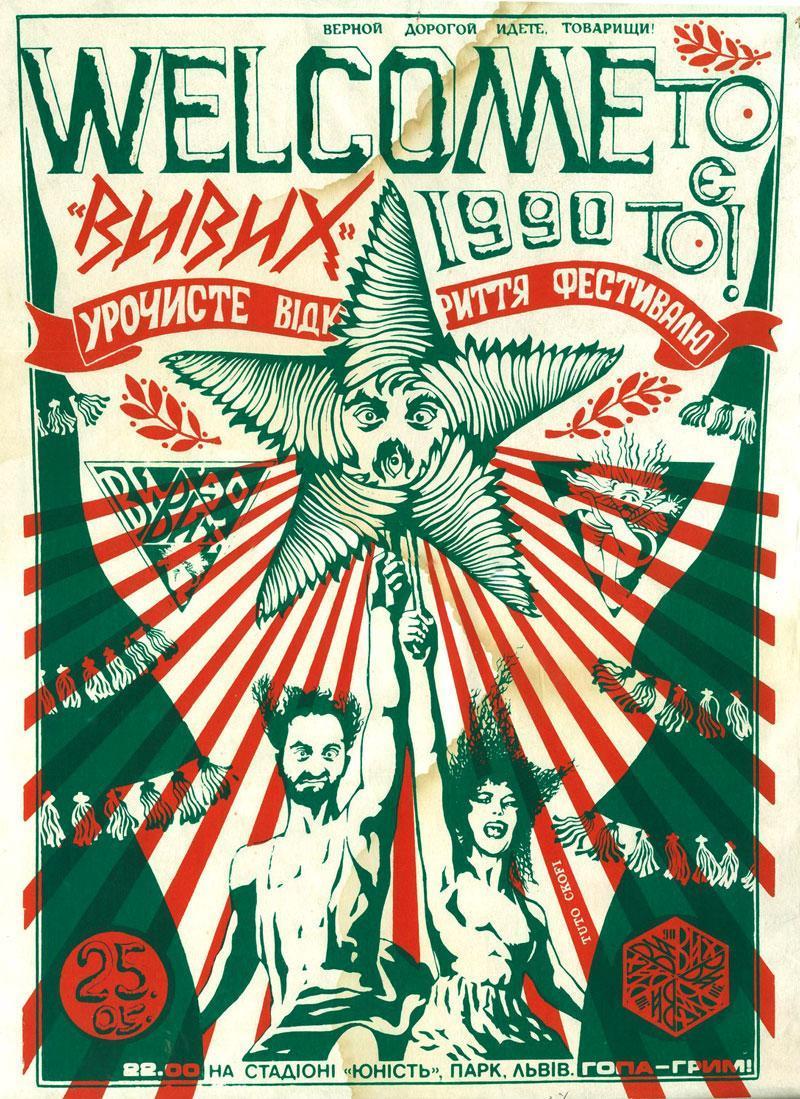

- Introduce the Vyvykh Festival (1990), the Chervona Ruta Festival, and the emergence of Ukrainian rock music as symbols of Ukraine’s cultural independence.

- Video Viewing (10 minutes)

- Show an excerpt where Gudimov describes his experience attending Vyvykh and his realization that the Soviet Union no longer existed for him (suggested clip: 00:22:28 – 00:26:00).

- Ask students to listen for how music and art helped create a national identity separate from Soviet culture.

- Class Discussion (15 minutes)

- Guide students through questions such as:

- What does Gudimov mean when he says: “We were already different. For us, the Soviet Union did not exist at all”?

- How did festivals like Vyvykh and rock music contribute to Ukraine’s cultural separation from Russia?

- How can music and festivals influence political and social change?

- Are there modern examples of music and art being used as political tools?

- Guide students through questions such as:

- Group Activity (5 minutes)

- Divide students into small groups. Each group should create a short social media campaign (a poster, slogan, or playlist) that highlights the power of music in social movements.

- Wrap-up and Homework (5 minutes)

- Summarize the discussion and assign students to write a short essay on how music and art can be used as tools of political expression.

Supplementary quote from the interview to facilitate discussion:

“After the Vyvykh concert in 1990, it was clear to me that I was going into music. We saw a huge layer of independent culture, and we realized we didn’t need the Soviet Union at all anymore.”

Poster for the 1990 Vyvykh festival.

Call to walk the streets before the festival’s closing concert.