Georgia – Eyewitnesses

Giorgi Meladze is an Associate Professor at the School of Law at Ilia State University in Tbilisi, Georgia. A former activist in the KMARA movement, a youth-led civic initiative opposing Shevardnadze’s regime in the early 2000s, he brings years of experience in training grassroots organizations and human rights activists both in Georgia and internationally. Giorgi is also one of the organizers of the ჯიუტი/GEUT (“Stubborn Resistance”) movement in Georgia.

In 1986, Rusudan Kobakhidze graduated from the Department of Classical Philology at Tbilisi State University. She later pursued a Doctoral Program in Byzantine Philology at the same university, earning her PhD in 2017. Since 2014, she has been a researcher at the Soviet Past Research Laboratory, and since 2018, she has taught Georgian Language and Literature at the Green School. Starting in 2020, Rusudan has been teaching an academic writing course for ISU Master’s students specializing in Modern Georgian History.

Tasks

Giorgi Meladze

Introduction: Understanding the Context of the Interview

On March 7, 1992, Eduard Shevardnadze, the former Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, arrived in Georgia. His arrival followed an armed coup d’état that had overthrown the government of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the previously elected president. Shevardnadze took control of the government from the leaders of the coup and gradually began consolidating power.

Shevardnadze’s presence in the country was soon followed by international recognition for Georgia. Over time, despite being engulfed in civil strife and war, the situation in the country stabilized. State institutions were developed step by step, and on August 24, 1995, the first Georgian constitution after the collapse of the Soviet Union was adopted.

Despite this relative stability, the state faced severe economic instability exacerbated by an energy crisis and widespread corruption. During this period, discontent with Shevardnadze’s government grew. Youth protest movements appeared, with university students taking an active role. Their primary target was corruption within universities.

In 2001, students at Tbilisi State University established the youth political movement “Kmara.” The emergence of such movements encouraged student protests to extend beyond university campuses, taking on a broader anti-government character.

A turning point that sparked widespread public protests, eventually culminating in the Rose Revolution, was the November 2, 2003, parliamentary elections. The government’s mass falsification of these elections triggered protests in the capital and other regions. Ultimately, on November 23, 2003, President Shevardnadze resigned and new elections were called.

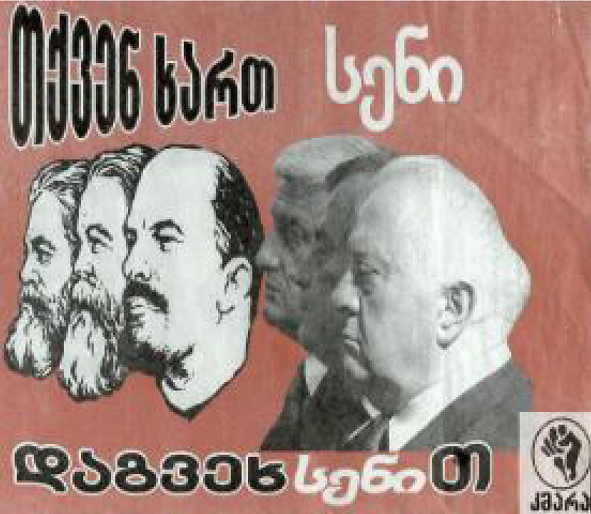

Kmara anti-government poster

Kmara activists of “Kmara”, 2003

Student Movements and the Rose Revolution: The Story of Giorgi Meladze

Giorgi Meladze is an associate professor of law at Ilia State University. Since the late 1990s, starting from the age of 19-20, he has been actively involved in student protest movements. This included being a member of Kmara, which significantly contributed to mobilizing young people during the Rose Revolution.

Meladze shares his perspective on the Rose Revolution as well as what happened after the peaceful regime change on November 23, 2003. He discusses the processes that preceded the revolution, the prevailing sentiments within society, and the willingness to bring about change that facilitated both resistance and inevitable transformation. Giorgi emphasizes that, despite this readiness for change, the Rose Revolution exhibited a spontaneous character.

To thoroughly understand the Rose Revolution and its aftermath, it is crucial to consider events from various perspectives. In this regard, Giorgi Meladze’s account is valuable as it highlights the role of a young civil activist and the risks faced by participants in mass protests.

The narrator notes that the government resulting from the revolution initiated various reforms. While he acknowledges that the changes created an environment that allowed him to grow as an activist, he believes this may have been a unique privilege for him personally.

In the second part of the interview, Meladze discusses both the successful and unsuccessful reforms implemented by the new government, including police reform.

As with all oral histories, this narrative reflects the subjective experience and memories of the narrator. The information gathered in the interview is not necessarily generalizable to all activists who were in a similar position.

Timeline and Terms

- March 7, 1992: Eduard Shevardnadze returned to Georgia.

- August 24, 1995: The first post-independence constitution is adopted.

- 2001: Theformation of the student movement Kmara.

- September 17, 2003: Special forces raid the homes of Kmara activists several times.

- November 2, 2003: Parliamentary elections are held; the results are not recognized by opposition parties.

- November 14, 2003: Protesters surround parliament and the Chancellery with a living chain, demanding the resignation of President Shevardnadze.

- November 22, 2003: The first session of the newly elected parliament is disrupted by mass protests.

- November 23, 2003: President Shevardnadze announces his resignation.

- March 28, 2004: Parliamentary re-elections are held.

Assignment: Discussion and Role-Play (25 minutes) (IX-XI CLASSES)

Objective: To help students understand the events of the “Rose Revolution” from different perspectives, encourage critical thinking, and develop teamwork skills through role play.

Necessary Materials:

Interview (oral history) with Giorgi Meladze

Timecodes:

- 1:16-4:44 (Goals and Expectations)

- 4:45-8:02 (The Motivations of a Civil Activist)

- 8:32-11:51 (Citizens’ Expectations Before the Revolution and the Post-Revolution Reality).

- Flipchart (for writing down the main points)

- Papers and writing materials

- Role-play instructions

Preparation:

1. Introduction and Context Setting(5 minutes)

- Provide a brief introduction and description of the Rose Revolution and its significance to Georgia’s recent history.

- Contextualize the interview by analyzing the motives and experiences of the civil activist, highlighting that this is a personal, subjective story.

2. Divide into Groups and Distribute Roles (5 minutes)

Divide students into groups of 4-5 members.

Assign each group a different role related to the Rose Revolution:

- Group 1: Civil activists (protest participants)

- Group 2: Government representatives

- Group 3: Ordinary citizens

- Group 4: International observers (foreign journalists, diplomats)

3. Prepare for Discussion (10 minutes)

Provide orientation questions for each group:

- For Civil Activists: Why did you participate in the Rose Revolution? What future expectations did you have?

- For Government Officials: How did you perceive the protests? How did you plan to maintain order?

- For Ordinary Citizens: How did the protests affect your daily life? Did you hope for change?

For International - Observers: What was your position regarding the events in Georgia? What international significance could the peaceful revolution in Georgia have?

Ask students to note the main arguments and interesting points to use during the role play.

4. Prepare the Role-Play

Each group should prepare a short role-play plan from their perspective (2-3 minutes) to represent their position or action during the events of the Rose Revolution. They can choose from:

- A public assembly/protest

- A meeting between government officials discussing how to respond to the protests

- An everyday conversation between ordinary citizens expressing their hopes, fears, and anxieties

5. Present the Role-Play Performance

Each group has 2-3 minutes to present their position to the class through their role-play.

6. Summary Discussion (2-3 minutes)

After all groups have presented, summarize the task with a short class discussion. Reflection questions may include:

- Do all parties perceive large protest movements in the same way? What common and distinguishing features did you observe in the positions of the different groups?

- How did the role play help you understand the complex events of the Rose Revolution?

- Did you learn something new and interesting from this assignment?

Alternative Assignment: Understanding the Rose Revolution Through Role-Play (40 minutes total) (IX-XI Classes)

Objective: To explore the events of the Rose Revolution from multiple perspectives, enhancing critical thinking and developing collaboration skills through role play.

Materials Needed:

- Excerpts from the interview with Giorgi Meladze

- Flipchart for notes

- Papers and writing tools

- Role-play instructions

Assignment Steps:

1. Introduction and Context Setting (5 minutes)

Begin with a brief, engaging introduction to the Rose Revolution, emphasizing its impact on Georgian society.

Introduce the civil activist Giorgi Meladze and highlight why his personal story is valuable for understanding these events.

Timecodes:

- 1:16-4:44 (Goals and Expectations)

- 4:45-8:02 (The motivations of a Civil Activist)

- 8:32-11:51 (Citizens’ Expectations Before the Revolution and the Post-Revolution Reality).

2. Watch Interview Excerpts (10 minutes)

- Play the selected excerpts from Giorgi Meladze’s interview that capture his experiences and insights.

- Ask students to note down key words, emotions, or events that resonate with them.

Group Formation and Role Assignment (5 minutes)

Divide students into three groups:

- Group 1: Civil activists (protest participants)

- Group 2: Government representatives

- Group 3: Ordinary citizens

Clearly outline each group’s perspective relating to Giorgi’s experiences.

Group Discussion and Role-play Preparation (10 minutes)

Provide each group with tailored discussion prompts:

- Civil Activists: Highlight what motivated Giorgi and others to protest. What were they hoping to change?

- Government Representatives: Consider how the government might have reacted to the protests. What challenges were they concerned with?

- Ordinary Citizens: Discuss how the protests might have affected daily life, as described by Giorgi. What were the public’s hopes or worries?

Instruct them to create a short (2-3 minute) role-play script, incorporating insights from the video.

Role-play Presentations (9 minutes; 3 minutes per group)

- Each group acts out their scenario, utilizing direct references and emotions highlighted in Giorgi’s narrative.

- Encourage creativity and emphasize emotional aspects to enhance understanding.

Reflection and Summary Discussion (6 minutes)

Lead a class discussion with questions like:

- What were some of the different perspectives you noticed?

- How did Giorgi’s personal story enrich your understanding of these events?

- What new insights do you have about the complexities of such a historical moment?

Rusudan Kobakhidze

Introduction to the Context

In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia underwent significant social, political, and economic changes. One of the most notable transformations was the resurgence of religion and the growing influence of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Church began to reclaim its role in society, politics, and culture, becoming a central player in post-Soviet Georgia. This religious revival has profoundly impacted community life, social values, and the political landscape.

This was not always the case. The state was officially atheistic during the Soviet era, a stance supported by the Communist Party. The Party systematically suppressed all religious groups as the belief in God was fundamentally at odds with materialism and socialism.

Although the Constitution of the Soviet Union enshrined freedom of belief and conscience (as stated in Article 124 of the 1936 “Stalin Constitution”) and claimed to separate church and state, the totalitarian regime brutally persecuted various faiths. The clergymen were targeted en masse during the Red Terror (1936-1937). Churches and monasteries were closed or destroyed and Soviet propaganda actively opposed all expressions of religion and faith. To facilitate this agenda, propaganda magazines were created, like “Saqartvelos Ugmerto/Mebrdzoli Ugmerto,” which was published in Georgia from 1933-1934 and laid the groundwork for subsequent mass clerical repression.

The totalitarian regime successfully subdued all religious groups, including the Orthodox Church. Following the Red Terror, all elected patriarchs were required to report to the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Furthermore, the Soviet state played an active role in the election of church leaders, a fact confirmed by Eduard Shevardnadze, who served as the first secretary of the Central Committee of Georgia from 1972 to 1985 (see video).

Religion and Faith in Transition: The History of Rusudan Kobakhidze

Rusudan (Rusiko) Kobakhidze-Aroshvili was born in 1964 in Tbilisi. She holds a doctorate in philology and is a teacher of Georgian language and literature. For the past 10 years, she has worked as a researcher at the Soviet Past Research Laboratory. Her research interests focus on the social and political processes in Georgia during the late Soviet period, with a particular emphasis on religion.

Rusudan’s memories begin in the 1970s but this interview specifically addresses Georgian society’s attitudes toward religion and faith during the late perestroika (restructuring) period. Kobakhidze reflects on prevailing attitudes towards the Orthodox Church in the 1980s and how these perspectives evolved alongside political and social changes.

She notes that as the movement for national independence gained momentum, society became increasingly religious. In the early 1980s, young people’s participation in Orthodox rituals emerged as a form of rebellion against the atheistic Soviet state.

Over time, the authority of the Georgian Orthodox Church has grown significantly. Public attitudes toward religion shifted notably after the collapse of the Soviet Union, largely driven by the national movement. The movement’s leaders frequently utilized Christian symbols, including the “Cross of Saint Nino.” Following the tragic events of April 9, 1989, where 21 people died after protesting the Soviet government, candles and crosses began to appear increasingly in public spaces, a phenomenon documented in the photo and video archives of that era.

According to Rusudan, since the 1990s, the Georgian Orthodox Church has established a strong connection between church and state. This relationship often attracts criticism as democratic governance models typically ensure that state and religious institutions remain separate. The narrator emphasizes that the constitutional agreement signed in 2002 between the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Georgian state discriminated against other religious groups.

It is crucial to recognize that each individual’s narrative is personal and subjective. Many factors influence their memories and perceptions. These include the surrounding environment, family background, education, and a person’s close friends and acquaintances.

Timeline and Terms:

- 1977: The consecration of Ilia II as Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia.

- 1987-1988: Georgia’s nationalist movement gains significant strength.

- April 9, 1989: The violent breakup of a peaceful rally by Soviet troops, resulting in the deaths of 21 people, including young women.

- October 22, 2002: A constitutional agreement (the so-called “concordat”) between the Georgian Orthodox Church and the state, granting special privileges to the Church.

- November 23, 2003: The Rose Revolution, leading to the ousting of Eduard Shevardnadze and a change of government.

- Enthronement: The ceremonial installation of a newly elected patriarch or pope.

- Military Council: The de facto government that took control after the 1992 coup d’état which led to the overthrow of the legitimate government.

Assignment: Small Group Discussion on Religion and Belief (9th-11th Grade)

- Total Duration: 45 minutes

- Preparation Time: 10 minutes

- Group Discussion: 25 minutes

- Presentation of Results: 10 minutes

Timecodes

- 0:51-3:23, 5:00-5:58 (Attitudes towards religion and religious holidays in the Soviet Union);

- 6:46-10:00 (The growth of the role of religion in the 1980s-1990s);

- 11:23-14:20 (The Orthodox Church in independent Georgia);

Instructions

Divide the Class: Organize students into groups of 4-5.

Assign Issues: Each group will focus on one of the following topics:

- Group 1: Repression Against Faith and Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda

- Group 2: The Collapse of the Soviet Union and the Growing Role of Religion

- Group 3: Religion and the State in Modern Georgia

Discussion Questions (Print and Distribute to Groups)

For the First Group: Repression Against Faith and Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda

Reflection Question: Think about the difference between faith and religion.

- What methods did the Soviet Union employ against religion, faith, and religious leaders (recall the material learned in the history lessons)?

- How did Soviet anti-religious propaganda portray the Church and its believers?

- How do you think people resisted a totalitarian regime that restricted their faith and religious life?

- In what ways did the Soviet state’s restrictions on faith and religious life impact people’s daily lives?

For the Second Group: The Collapse of the Soviet Union and the Growing Role of Religion

Reflection Question: Think about the difference between faith and religion.

- How did the collapse of the Soviet Union affect freedom of religion and belief?

- What role did the Orthodox Church play, and how did it support people during the transition period (during the collapse of the Soviet Union and the restoration of Georgia’s independence)?

- Do you think holidays like Christmas and Easter were celebrated in the Soviet Union? What has changed in this regard since the collapse of the Soviet Union?

For the Third Group: Religion and the State in Modern Georgia

Reflection Question: Think about the difference between faith and religion.

- Do you think society’s attitude toward religion has changed since the collapse of the Soviet Union?

- What attitudes do older generations have compared to younger generations towards religion in modern Georgia?

- According to the Constitution of the First Democratic Republic of Georgia (1921), no religion has priority. How important is it for the state to treat all religions equally?

- What role do major religions play in addressing poverty, social issues, and education in Georgia? Can you provide examples?

Group Discussion (25 minutes)

- Allow Discussion: Allow students to freely express their opinions regarding their group’s assigned issue.

- Brainstorming: Encourage students to share ideas, opinions, and associations related to the discussion topic on a presentation sheet.

- Teacher Facilitation: The teacher should circulate among the groups, providing guidance and support as needed, and introduce new perspectives to enhance the discussions.

Presenting Results (10 minutes)

Each group has one minute to summarize and present the key points of their discussion. Summaries can be delivered by selected speakers from each group.

Final Words (2-3 minutes)

The teacher summarizes key issues raised during the discussions and reflects on important insights from each group, emphasizing the overall themes related to religion, society, and national identity.