Dissident and Informal Cultures and the Collapse of the USSR

Exploring the Hidden Resistance in Soviet Society

On the surface, the Soviet Union appeared to be a monolithic society where the Communist Party completely dominated all spheres of society, exercising successful ideological control.

In fact, this uniformity of the ideological and political landscape hid quite a few areas where the Party had failed to achieve full control over people’s minds, where certain loopholes existed for “dissent”. Dissidents were an extremely vulnerable group in the Soviet Union. Various youth movements, but also intellectuals and dissidents can be included in this category.

The study of informal movements in the Soviet state is still dominated by the Moscow-centric paradigm, which focuses on the actions of the Moscow and Leningrad intelligentsia. At the same time, the opposition between the “center”, where the universalist agenda of human rights was developed and supported, and the “periphery” (union republics), where national demands were more important, is constantly emphasized.

The Emergence and Impact of National-Cultural Movements

Naturally, it was fraught and dangerous to enter into a full-fledged confrontation with the Soviet state. The latter had a powerful suppression apparatus: dissidents were watched over by the almighty State Security Committee, the justice system was able to easily fabricate prison terms, even psychiatric hospitals were used to isolate dissidents.

For this reason, those who disagreed with the Communist system had no choice but to play on the same field. The most prominent part of the dissident movement, the human rights activists, appealed to the official documents enshrined in the Soviet state – the USSR Constitution or the ratified Helsinki Declaration of Human Rights. The reference to the original Bolshevism was also used to criticize the existing system, and then the late Soviet USSR was seen as a deviation from the ideals of Leninism, which allowed critics to also shy away from direct repression.

Figure 1: Dissidents at a rally in Belarus, 1990. Mikhas Kukabaka pictured speaking.

Indeed, such a division existed, but we note that national demands also allowed us to appeal to the Leninist ideal of the Soviet Union, which declared the emancipation of national cultures that had been suppressed under the tsarist regime. Already in the early 1980s, i.e. even before perestroika began, one could note the growth of national-cultural movements, which grew like mushrooms in all the Soviet republics. Their agenda was similar in many respects, they demanded a better social status for the national language, which was under threat due to the all-Soviet privileged position of the Russian language. Also popular were demands for the protection of cultural and historical heritage, especially architectural monuments, which were often interpreted by the communist authorities as symbols of a bygone era, feudal oppression and religious blight. These movements often brought together young people who actively used their native language in communication, were interested in history, traveled the country, and actively revived folklore traditions and holidays, which for young people became a real basis of national culture.

Western Influence and the Rise of Soviet Youth Subcultures

By the 1980s, it was clear that the Soviet Union had lost the Cold War to the West in terms of fighting for the minds of young people. To control the younger generation, the Communist Party used the tools of the Pioneer and Komsomol, which were supposed to provide unified ideological training. But it was this unification with the regulation not only of ideological views, but even of appearance (a Pioneer must wear a school uniform and tie! A Komsomol member cannot wear clothes that stand out, even the length of his hair must conform to the norm!) was most irritating to young people. The West was the realm of freedom, where you could choose any lifestyle that suited you, and rock music became a symbol of protest against endless and boring regulations.

Figure 2: Children receiving their Komsomol memberships in Moscow’s Red Square, dressed in the typical uniform.

The beginning of perestroika, with its slogans of glasnost and revision of outdated dogma, effectively blew up the previous balance of power. Informal movements gained access to the press, and publications that criticized the Soviet system or promoted new youth values were the ones that began to appear in huge numbers.

The Demise of Communist Control and the Rise of Informal Movements

The other half of the 1980s and early 1990s was also the “golden age” of youth subcultures. The main source of cultural borrowings were Western countries, from where the youth styles formed: hippies, punks, skinheads, and metalheads. Each of these subcultures was based on a particular musical style, and an emotional community was formed around listening to music together, allowing for interpersonal relationships. Each subculture also created an easily recognizable visual style (clothing, hairstyles, stripes), by which you could tell who you were meeting on the street (and whether you needed to fight with them); for example, by the color of the laces (red or white), you could determine what ideological orientation the skinhead you met adhered to. Knowledge of these codes was extremely important.

The controlling bodies began to lose out cleanly to this subcultural boom that was sweeping Soviet youth. Joining the Komsomol no longer seemed like an attractive magnet and a promise of successful integration into adult life. On the contrary, it began to be perceived as a burden, whereas free life was out there. Stable places of communication were forming, where one could chat informally with peers, consume alcohol, and listen to music.

Figure 3: Antis, a postmodernist rock band, on stage in Vilnius, 1987. Their name, meaning “duck” in Lithuanian, refers to false reports and is a play on the Soviet-era newspaper, Tiesa. It is also interpreted as “Anti-S” for “Anti-Soviet.”

Changes in economic regulation led to the birth of a new industry, which allowed for making money from youth hobbies. Huge print runs of youth magazines featured obligatory posters of rock musicians, rock concerts moved from garages to stadiums, to the concert “Monsters of Rock” in Moscow in 1991, which gathered about 700 thousand spectators, who flocked there from all over the Soviet Union.

The Rise of Criminal Culture: Struggles for Territory and Conflicts with Informals

But not everyone became “informals,” there was also the flowering of a criminal culture based on the cult of strength and hypertrophied masculinity (the so-called Gopniks). In the late Soviet Union, numerous youth associations were created with the goal of “fighting for their territory”. Going to another district of a major city becomes a dangerous adventure, as it implies entering a zone jealously guarded by local gopniks. In addition to the struggle for zones of influence, which becomes the basis for the formation of criminal groups, a particularly acute conflict unfolds with the informals. Komsomol bosses watch with horror the waves of violence that seize the streets of large cities, with clashes between gopniks from different neighborhoods, or between gopniks and informals. In turn, there are violent clashes between musical subcultures as well, only hippies try to hold on to their peaceful philosophy. Freedom also has its dark side.

Figure 4: Typical Russian youths from the city of Tyumen.

The Path to Political Protest and the Collapse of the USSR

But it is not just a question of lifestyle; the rejection of the communist worldview is a direct path to political protest. The informal youth organizations that defended monuments and organized folklore festivals suddenly became a serious political force, with which the previously all-powerful Communist Party was already forced to reckon.

The former dissident movements were institutionalized, gaining legal status and becoming involved in the political struggle, and a wave of People’s Fronts was sweeping through the Soviet republics. These fronts were in some ways united, all initially critical of the current government from the perspective of a return to the true ideals of communism, but gradually moving toward increasingly harsh criticism with demands for greater democratic rights and national autonomy.

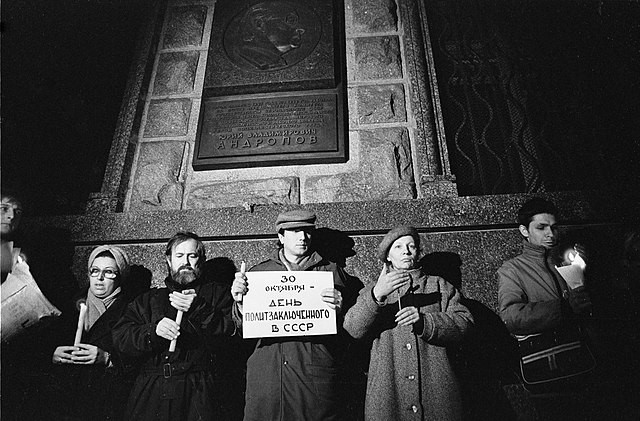

To a large extent, the policy of glasnost initiated by the Soviet leadership provided a powerful tool to discredit the entire communist system. This refers to the truth about the scale of Stalinist repressions, a wave of publications about victims of repression (in Ukraine, the silenced truth about the scale of the Holodomor is also revealed), places of executions become “memory sites” where movements opposed to the communist authorities hold rallies. In Ukraine and especially in Belarus, the Chernobyl disaster was an additional trigger for politicization of the informal opposition, and accusations of local authorities’ detrimental and passive response to this tragedy became an additional serious accusation against the Communist authorities.

Figure 5: Protestors forming a ring around the KGB building in Moscow on Political Prisoner Day, 1989, in memory of the victims of Stalinism.

The Soviet Union began to rapidly disintegrate at the national seams and also uncovered numerous ethnic conflicts. Speakers from the dissident national intelligentsia circles, who believe that this is the best time to implement their demands, to make demands for independence rather than autonomy, are seizing the microphones. Slogans that used to be a reason for repression are spreading from the pages of newspapers (and newspaper circulation is higher than ever) and television.

The transition of the former Soviet republics to independence has given extraordinary opportunities to former dissidents. Some of the former dissidents broke into the power elite, Zviad Gamsakhurdia even became president of Georgia. But success was not found everywhere; in many countries, the former party elite was able to retain some control by taking the upper hand during the transition (as happened in Belarus and Ukraine). But by no means always those people who demanded democratic reforms, having climbed to the top of power, were able to adhere to their declared principles.

The new rules gave many people a chance: politicians and rock musicians alike. But it was hard for most young people to take advantage of these chances, as material insecurity, poverty, and street violence were the main hallmarks of the new era. But their newfound sense of freedom gave them hope for a change for the better.

Eyewitnesses

Tasks

Duration: 90 minutes

Target audience: Students 14+

Needed materials: Internet, projector, flipchart/board, markers

Watch both interviews (Vladislav and Roby) – split into two groups, each watching a different video, then discussing and comparing together. (30 minutes)

Vladislav: https://youtu.be/qcC70s5Mh5w

Robi: https://youtu.be/tWX5ZeqnEhA

Discuss the following questions with the group:

- What niches in the Soviet system did young people find to form their own rock bands that clearly did not meet the normative expectations of cultural functionaries? (20 minutes)

- How did the lives and working conditions of rock musicians change after the collapse of the Soviet Union? (general question, 10 minutes)

- Search the Internet for videos and lyrics by Gods Tower and Outsider. Think back to your favorite musicians, do you see any differences, what and how these bands sing about? (general question, 15 minutes)

- Are any of your friends punk or metal or other subcultures? Are these musical trends a thing of the past, or do they have their place with current youth? (general question, 15 minutes)