Belarus at the crossroads of an era

The years 1990-1991 were a crossroads of historical epochs for Belarus. During this historically very short period, Belarus experienced several cardinal changes – the collapse of the socialist economy, social and political awakening, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the emergence of an independent Belarus, and the start of profound socio-economic and political reforms.

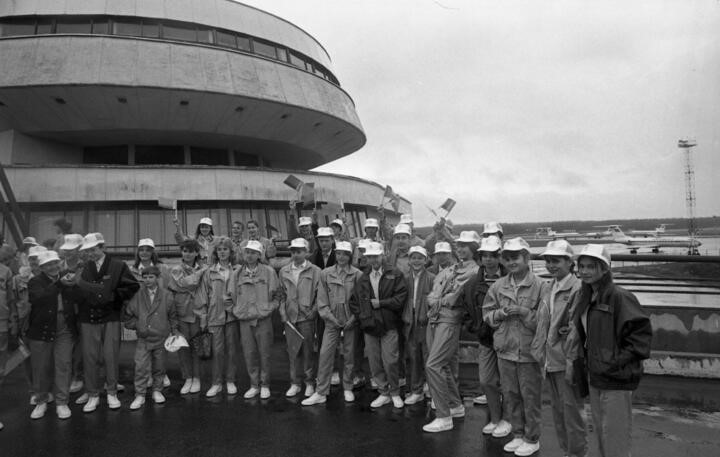

Participants in the Belarusian Popular Front movement under the leadership of Zenon Pazniak in the late 1980s.

A Conservative Approach to Perestroika and the Fallout from the Chernobyl Disaster

In the late 1980s, Belarus looked like one of the most conservative parts of the USSR on its European territory. This image was formed through the position of the BSSR authorities towards political and social problems in the country during the period of Perestroika. The authorities of the BSSR were the least inclined to reform the economy and social structure.

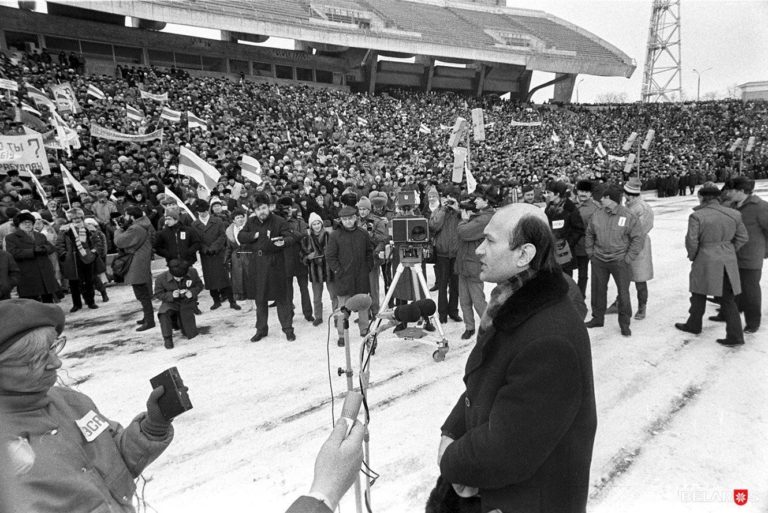

Schoolchildren from contaminated areas of Minsk Region at the Minsk-2 airport before flying to Italy for recuperation, early 1990s.

On the one hand, such a conservative policy could for some time slow down the deterioration of the living conditions of the people of Belarus; on the other hand, it did not allow an adequate response to the challenges of the time. A bright example of such a situation was response to the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster on April 26, 1986. One third of the territory of Belarus was covered with radioactive substances, and nearly one fifth of the country’s population – 2.2 million people – found themselves contaminated land. Over five years, Belarus saw a 22-fold increase in thyroid cancer among children. The Soviet leadership failed to react promptly to the events and to comprehend the scale of the tragedy. Many people who found themselves in the radioactively contaminated zone, but were not subject to mandatory evacuation, were abandoned to their fate. Depression, psychological and social, was one of the most striking phenomena among residents of such regions. Many were forced to save their health and lives by choosing to leave their former places of residence. Thus, Chernobyl victims, including residents of affected areas, displaced persons, and those disabled by the disaster, formed a substantial portion of vulnerable groups during the Transit. Additionally, during this period, other at-risk groups emerged from various spheres: social and professional (engineers, technical staff, and large enterprise workers, along with a significant rural population), gender and demographic (primarily women, youth, and retirees), and national and religious minorities.

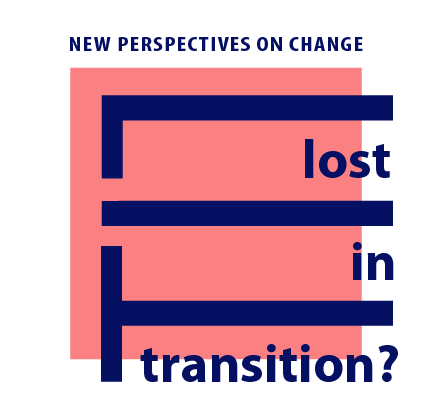

Dziady requiem rally, 30 October 1988, Minsk

Economic and Social Divide: The Struggles of Peasantry and Large Enterprise Workers

One of the most affected social groups as a result of the transformations of the late 1980s and early 1990s was the peasantry. The previous system of management in the agrarian sphere centered on large collective farms, had fallen into disrepair. Low efficiency in the agrarian sector was recognised by the Soviet leadership, which used the name “Food Problem” for this purpose. But no clear perspective for the future was offered. Belarusian villagers found themselves in the middle of this economic and social divide, which further aggravated their situation. Although certain signs of a new era began to emerge in the countryside: the emergence and slow spread of larger scale farming.

3 April 1991, 320,000 workers marched in columns to the Government House in Minsk

Another vulnerable group, whose situation has worsened considerably, are workers in large enterprises. This was due to the collapse of the former system of economic management and the sharp decline in production during 1991 and the following years (the country’s GDP in 1995 was 65% of its 1990 level). But the scientific and creative intelligentsia also found themselves in a difficult position. The Soviet system of scientific and cultural organization had provided funding for large scientific and artistic projects from the state, and, in the context of a deepening economic crisis, there were fewer and fewer opportunities for such funding. Many musicians and artists were forced to look for opportunities to work abroad as a means of survival. The same tendency was apparent among scientists and engineers, but many simply left to pursue other occupations which did not require such qualifications. The rise of “shuttle traders” – individuals importing goods for resale – became widespread. People from various professions, struggling to adapt to new economic realities, joined this growing trade.

On the other hand, the perception of human rights, which encompassed more than just social rights, began to take shape in the mass consciousness during the Perestroika period. The deterioration in citizens’ economic situation went hand in hand with the emergence of ideas concerning national minorities and gender rights.

Unemployment and Inflation: Rising Protests and Asserting Rights in the Early 1990s

Meanwhile, the phenomenon of unemployment became prominent during this transition period. No able-bodied demographic or social group of workers escaped unemployment. But unemployment was most widespread among women, with women accounting for 80% of the unemployed in 1991.

Unusual for the inhabitants of Belarus was the great increase in prices. Besides, it occurred in the absence of social protection during the transition to a market economy. On the other hand, the degree of liberalisation of political relations achieved during the years of perestroika enabled different sections of society to assert their rights. On April 3-5, 1991, a number of large Belarusian enterprises stopped their work, about 320,000 workers marched in columns to the Government House in Minsk. Orsha workers took more radical steps – they staged a “sit-in” strike on the railway tracks, thus blocking the movement of trains. In total, according to official data, in 1990 and the first half of 1991, there were 247 protests in Belarus, which were attended by approximately half a million people. Initially the protests were spontaneous, but gradually the labour movement was joined by some political parties and public organisations, which gave the social protests a political dimension.

The short "Window of Freedom": Opportunities and Challenges during the Transition Period

The clothing market at the Dynamo stadium, 1996. Photo by A. Tolochko, BelTA

However, when speaking about the increasing economic difficulties for many social and socio-cultural groups in Belarus during the Perestroika period, it should be noted that this was a time of social dynamics, relatively open discussions and the belief of many people that achieving a better life was possible. For the first time in recent decades independent public organisations and the beginnings of political parties began to arise. Believers were finally granted religious freedom.

In these difficult and contradictory conditions a modern Belarus was born, with its own achievements and failures. Transition created additional problems for vulnerable groups (Chernobyl victims, rural inhabitants and workers of large enterprises, scientific intellectuals, national minorities, etc.). The USSR’s collapse significantly impacted the Belarusian population, disrupting their customary way of life. In macroeconomic terms, a notable shift occurred in 1991 when Belarus transitioned from a major exporter to an importer of commodity products. But, as many of these people admit, 1991 also brought new opportunities for them. From 1991 to 1994, a “window of freedom” emerged, enabling legal private economic and public political activity. This experience of freedom held significant value for Belarusian society. After the 1994 presidential election and the onset of an authoritarian regime, the gained economic freedoms and civil experience allowed Belarusian society to function despite limited political rights.

Timeline

-

The accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, one of the biggest man-made disasters in the history of mankind, which had fundamental social and political consequences 26.04.1986

-

Creation of the Historical-Educational Society for the Remembrance of Victims of Stalinism "Martirologue Belarus" and the Organisational Committee of the Belarusian Popular Front for Perestroika "Revival" (BPF) 19.10.1988

-

Dispersal of the requiem rally "Dziady" (Day of Remembrance of the Ancestors) 30.10.1988

-

The Belarusian language was granted the status of the state language (adoption of the Law on Languages in the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic) 26.01.1990

-

Elections to the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR, the only elections in Soviet Belarus that were held on an alternative basis 04.03.1990

-

Adoption by the Supreme Soviet of the Belarusian SSR of the Declaration on State Sovereignty of the Belarusian SSR 27.06.1990

-

Mass strikes and demonstrations in connection with price hikes 03-09.04.1991

-

"August putsch": an attempted coup d'etat in the USSR; the authorities of the BSSR actually supported the coup plotters (GKChP) 19-21.08.1991

-

The country received a new name, the Republic of Belarus, and new state symbols 19.09.1991

-

The signing of the Belovezhskaya Agreement, which put an end to the existence of the USSR 08.12.1991

-

Speaker of Parliament Stanislav Shushkevich is dismissed 26.01.1994

-

The first presidential elections in Belarus, bringing Alexander Lukashenko to power 23.06.1994, 10.07.1994

Eyewitnesses

Tasks

Topic: Survival strategy for people in a critical era

The duration of the class (meetings): 45 minutes.

Target audience: Students 14+

Materials: links to videos or technical means for viewing in general (projector, screen).

Class based on:

“Belarus at the Turn of an Epoch” study module; interviews with Sergei Bandarenko, Nina Stuzhinskaya, and Sofia Savelova.

Abstract: During the “long” transition (1986-1994), Belarusians faced serious socio-economic challenges caused by two cardinal phenomena – the catastrophe at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986 and the collapse of the planned socialist system, the consequences of which became particularly acute through commodity shortages in 1989-1992. The inhabitants of Belarus after the Chernobyl disaster were forced to think about their physical survival and preservation of their health. And in the conditions of the collapse of the former economic model, many Belarusans were engaged in the search for means of subsistence and new kinds of activity.

Format of the exercise:

- The Chernobyl disaster

Briefly tell (remind) the students (panelists) about the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and show a map of the contamination resulting from the disaster.

Interviews with Sergey Bandarenko (1:06 – 2:34), Nina Stuzhinskaya (8:48 – 9:28; 10:00 – 11:40).

Fig. Cesium-137 contamination of the territory of the Republic of Belarus, as of 1986 (Source: 35 years after the Chernobyl disaster: results and prospects of overcoming its consequences : national report of the Republic of Belarus / Department of the Chernobyl NPP disaster consequences elimination of the Ministry of Emergencies of the Republic of Belarus. Minsk, 2020).

Ask the following questions:

— How should the authorities act in a situation where it is necessary to save people during man-made disasters?

— What can people do when they have to save their lives and health during disasters? (evacuation, forced relocation, helping others, migration…)

Case of Sergei Bondarenko: Because of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, Sergei was forced to leave his homeland in Svetlogorsk district of Gomel region. He lived and worked in Russia. Then Sergei returned to Belarus. The Soviet Union collapses. Sergei is forced to look for a new place of residence. Officially, his former place of residence is not on the list of the most contaminated areas, but it is dangerous to live there. He is forced to look for a new home and learn new professions.

The case of Nina Stuzhinskaya: as one of the manifestations of self-organization of Belarusian society, Nina participates in the distribution of humanitarian aid and organizes educational courses.

- The Collapse of the Soviet Planning System and the Commodity Deficit

Briefly tell (remind) the students (panelists) about the disaster of the economic and social problems that Belarusan society faced at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. Give examples from the following memoirs, and view excerpts from interviews with Sergey Bandarenko (4:40 – 5:30; 5:58 – 6:57), Nina Stuzhinskaya (0:40 – 2:34).

Since 1989, in some regions of the USSR the card (coupon) system for scarce goods was introduced. In Belarus the card-distribution system functioned in the form of the so-called “Buyer’s cards” for purchase of industrial goods, separately – for men’s and women’s products (Order of the Ministry of trade of the BSSR and Belcoopsoyuz of September, 24, 1990 № 52/91) and coupons – for foodstuffs.

Since 1990, an avalanche-like process of inflation, rising unemployment, and the closure of industrial enterprises began to develop. Under the conditions when the single post-Soviet ruble zone was functioning, the cost of many consumer goods in Belarus remained lower than in the neighboring countries of the former USSR. Decree No. 423 of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus “On Additional Measures to Protect the Consumer Market of the Republic” of November 14, 1991, introduced a one-time coupon for circulation with the Soviet ruble in January 1992. It was possible to buy goods in Belarus for Soviet rubles only with such coupons. Coupons were issued at the place of work, service or study on presentation of a passport and proof of residence for 60% of net earnings. Pensioners received coupons along with their pensions. For children consumer cards were issued through the housing authority. These were cut coupons, printed on a single sheet, which were actually the first state-issued paper quasi-currency of independent Belarus. Coupons and coupons were valid in Belarus until 1992, and for some food products even until 1993.

In the conditions of a deep crisis, many residents of Belarus had to look for new sources of income, change their profession and find new spheres of activity. The “shuttle traders” – small wholesale and retail traders of consumer goods using the “shuttle” trade method – became a symbol of the era: independent delivery of a small batch of goods from the place of purchase, quick sale at “their” market, the next trip along the same route. Many people found themselves in handicraft activities. Farmers appeared in the countryside. Some new activities were legalized by the state. The population had the opportunity to engage in legal individual entrepreneurship and to travel abroad without hindrance.

Testimony:

Yadviga from Minsk worked as a cashier in a vegetable store on Chkalova Street in 1991. She recalls how trade was done at that time.

– You took goods for a certain amount of money and accordingly you had to provide coupons for that amount. They were cut out separately. Coupons were a confirmation that the buyer had the right to buy the goods. At that time some goods were in short supply, coupons were introduced so that they were not given out too much. In the evening we had to count how much money was in the cash register and how much in coupons. We had to make it all add up, it was very strict with counting and control.

Store employees collected and turned in coupons to special card bureaus.

– At that time there was a shortage of buckwheat, rice, pasta and sugar. The issue of these goods was limited. The coupons indicated what specific goods could be bought. There was a separate queue for the items that could be purchased with coupons. Customers swapped coupons, depending on who needed what goods. But I didn’t see any fake papers.

Vitbichi” newspaper, December 1991:

“Of course, strict control is necessary, but… This innovation has many negative aspects. All of us will be attached to the store where we live, and there is no guarantee that the nearest one will be there. And after work we are unlikely to be able to buy anything because of the huge lines. We buy food where and when we have to”.

“Sovetskaya Belorussiya” newspaper, December 20, 1991. Article “It is better to buy a product with inconveniences than not to buy it at all”:

“The introduction of coupons will by no means make our lives less troublesome than they have been so far. Moreover, the lines are bound to become longer, and both sellers and customers will become more impatient… There is no problem with talons. We got used to them. Now we should get used to coupons too. And then, having studied all the anti-market sciences, we should reject them all at once: we don’t want to be slaves of papers, papers and paper! We want to earn lots of money and buy whatever we want with it! We are worse off than others!”.

Sovetskaya Belorussiya newspaper, December 21, 1991:

“As stated, the government is not going to mislead the people and says frankly that for the next year and a half the standard of living of those living on fixed incomes will decrease. Prices, on average, will be increased 3.3 times, but not for all types of goods equally. In short, we must get used to living in the new conditions of free prices and free enterprise.

From the memories of Galina, who was in the shuttle business in the 1990s https://people.onliner.by/opinions/2020/03/05/mnenie-1239 :

“We sold everything: clothes, shoes, dishes. There was almost nothing in the stores at that time. When free trade appeared, the markets were the first to fill up. Probably a lot of these goods were sewn “in basements” and passed off as well-known brands, but people did not know much about it at that time and not many people knew about boutiques. But people wanted to dress nicely.

Racketeering was a serious obstacle at the time. What was it? The racketeers controlled everything: the stores, the markets… Young guys would come to you, and the amount we had to pay for “protection” would be stipulated. If you didn’t agree with these guys, you could get into trouble. One day, for example, a car got in the way of our bus. A guy got on the bus, he pointed a gun at me and said: “Turn around and go back.” What to do – we turned around and drove away. Another group of shuttles, as far as I know, shot at the wheels of the bus, miraculously they didn’t have a serious accident. But most often it was possible to negotiate with them, the main thing was to pay.

It’s even difficult for me to explain to you how difficult it is. Especially the women. And women were the majority, there were usually 1-2 men in a group of 20 people. I think it was because men back then were a bit shy to trade, and women were more communicative and probably more hardy.”

Ask the following questions:

— why was the card (coupon) distribution of goods introduced in the USSR from 1989 and in the Republic of Belarus from 1992?

— What new activities have people engaged in in the face of rising unemployment and business closures? (shuttle trade, crafts, farming)

— How did a craftsman (artist) have to make a living from his work? (travel to sell his products himself)

— What kind of hardships did you have to endure?

— What changed in the state’s attitude toward individual economic activity after 1991? (It became legal)

Compare the personal strategies after 1991 of Sergei Bandarenko, Nina Stuzhinskaya, and Sofia Savelova.

- Learning to live in a new environment

Watch the interviews with Sergey Bandarenko (6:58 – 9:14), Nina Stuzhinskaya (12:42 – 13:28).

Ask the following questions:

- What have people who have gone through all the difficulties of the transition (transformation) era gained? (experience of living under new social conditions)

- How do such people view their lives independent of government care?

Illustrations in the .docx file

The Collapse of the Soviet Planning System and the Commodity Deficit

Briefly tell (remind) the students (panelists) about the disaster of the economic and social problems that Belarusan society faced at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. Give examples from the following memoirs, and view excerpts from interviews with Sergey Bandarenko (4:40 – 5:30; 5:58 – 6:57), Nina Stuzhinskaya (0:40 – 2:34).

Since 1989, in some regions of the USSR the card (coupon) system for scarce goods was introduced. In Belarus the card-distribution system functioned in the form of the so-called “Buyer’s cards” for purchase of industrial goods, separately – for men’s and women’s products (Order of the Ministry of trade of the BSSR and Belcoopsoyuz of September, 24, 1990 № 52/91) and coupons – for foodstuffs.

Since 1990, an avalanche-like process of inflation, rising unemployment, and the closure of industrial enterprises began to develop. Under the conditions when the single post-Soviet ruble zone was functioning, the cost of many consumer goods in Belarus remained lower than in the neighboring countries of the former USSR. Decree No. 423 of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus “On Additional Measures to Protect the Consumer Market of the Republic” of November 14, 1991, introduced a one-time coupon for circulation with the Soviet ruble in January 1992. It was possible to buy goods in Belarus for Soviet rubles only with such coupons. Coupons were issued at the place of work, service or study on presentation of a passport and proof of residence for 60% of net earnings. Pensioners received coupons along with their pensions. For children consumer cards were issued through the housing authority. These were cut coupons, printed on a single sheet, which were actually the first state-issued paper quasi-currency of independent Belarus. Coupons and coupons were valid in Belarus until 1992, and for some food products even until 1993.

In the conditions of a deep crisis, many residents of Belarus had to look for new sources of income, change their profession and find new spheres of activity. The “shuttle traders” – small wholesale and retail traders of consumer goods using the “shuttle” trade method – became a symbol of the era: independent delivery of a small batch of goods from the place of purchase, quick sale at “their” market, the next trip along the same route. Many people found themselves in handicraft activities. Farmers appeared in the countryside. Some new activities were legalized by the state. The population had the opportunity to engage in legal individual entrepreneurship and to travel abroad without hindrance.

Testimony:

Yadviga from Minsk worked as a cashier in a vegetable store on Chkalova Street in 1991. She recalls how trade was done at that time.

– You took goods for a certain amount of money and accordingly you had to provide coupons for that amount. They were cut out separately. Coupons were a confirmation that the buyer had the right to buy the goods. At that time some goods were in short supply, coupons were introduced so that they were not given out too much. In the evening we had to count how much money was in the cash register and how much in coupons. We had to make it all add up, it was very strict with counting and control.

Store employees collected and turned in coupons to special card bureaus.

– At that time there was a shortage of buckwheat, rice, pasta and sugar. The issue of these goods was limited. The coupons indicated what specific goods could be bought. There was a separate queue for the items that could be purchased with coupons. Customers swapped coupons, depending on who needed what goods. But I didn’t see any fake papers.

Vitbichi” newspaper, December 1991:

“Of course, strict control is necessary, but… This innovation has many negative aspects. All of us will be attached to the store where we live, and there is no guarantee that the nearest one will be there. And after work we are unlikely to be able to buy anything because of the huge lines. We buy food where and when we have to”.

“Sovetskaya Belorussiya” newspaper, December 20, 1991. Article “It is better to buy a product with inconveniences than not to buy it at all”:

“The introduction of coupons will by no means make our lives less troublesome than they have been so far. Moreover, the lines are bound to become longer, and both sellers and customers will become more impatient… There is no problem with talons. We got used to them. Now we should get used to coupons too. And then, having studied all the anti-market sciences, we should reject them all at once: we don’t want to be slaves of papers, papers and paper! We want to earn lots of money and buy whatever we want with it! We are worse off than others!”.

Sovetskaya Belorussiya newspaper, December 21, 1991:

“As stated, the government is not going to mislead the people and says frankly that for the next year and a half the standard of living of those living on fixed incomes will decrease. Prices, on average, will be increased 3.3 times, but not for all types of goods equally. In short, we must get used to living in the new conditions of free prices and free enterprise.

From the memories of Galina, who was in the shuttle business in the 1990s https://people.onliner.by/opinions/2020/03/05/mnenie-1239 :

“We sold everything: clothes, shoes, dishes. There was almost nothing in the stores at that time. When free trade appeared, the markets were the first to fill up. Probably a lot of these goods were sewn “in basements” and passed off as well-known brands, but people did not know much about it at that time and not many people knew about boutiques. But people wanted to dress nicely.

Racketeering was a serious obstacle at the time. What was it? The racketeers controlled everything: the stores, the markets… Young guys would come to you, and the amount we had to pay for “protection” would be stipulated. If you didn’t agree with these guys, you could get into trouble. One day, for example, a car got in the way of our bus. A guy got on the bus, he pointed a gun at me and said: “Turn around and go back.” What to do – we turned around and drove away. Another group of shuttles, as far as I know, shot at the wheels of the bus, miraculously they didn’t have a serious accident. But most often it was possible to negotiate with them, the main thing was to pay.

It’s even difficult for me to explain to you how difficult it is. Especially the women. And women were the majority, there were usually 1-2 men in a group of 20 people. I think it was because men back then were a bit shy to trade, and women were more communicative and probably more hardy.”

Ask the following questions:

— why was the card (coupon) distribution of goods introduced in the USSR from 1989 and in the Republic of Belarus from 1992?

— What new activities have people engaged in in the face of rising unemployment and business closures? (shuttle trade, crafts, farming)

— How did a craftsman (artist) have to make a living from his work? (travel to sell his products himself)

— What kind of hardships did you have to endure?

— What changed in the state’s attitude toward individual economic activity after 1991? (It became legal)

Compare the personal strategies after 1991 of Sergei Bandarenko, Nina Stuzhinskaya, and Sofia Savelova.

Learning to live in a new environment