Belarus – Eyewitnesses

Vintsuk (Valentyn) Viachorka is a Belarusian politician and linguist, and a pioneer of the independent youth movement of the 1980s. Coming from a Soviet party elite family, he rejected Soviet ideology, seeking cultural and national identity. While a student at Belarusian State University, he co-founded the youth organizations “Maistroŭnia” and “Talaka” and played a key role in the Confederation of Belarusian Youth Associations. In the late 1980s, he became a founding member of the Belarusian Popular Front (BNF), leading the organization from 1999 to 2007. Since 2020, he has lived in exile.

Siarhei Chareuski is a Belarusian art historian, artist, journalist, and public figure. His biography reflects the shifts in creative and social choices made by young people in a major Belarusian city during the 1980s. Siarhei received a solid foundation in art education, graduating from the Glebov Art College in Minsk (1982–1987). While still a student, he became involved in informal youth cultural groups, such as “Maistroŭnia” (the Belarusian Singing and Drama Workshop, which ceased operations following a conflict with authorities in 1984) and “Talaka” (1985–1990). Since the early 1990s, Siarhei has been actively collaborating with independent Belarusian journalism. He created artistic compositions for the newspaper Svaaboda and, in 1991, contributed to the revival of “Nasha Niva”, a legendary symbol of national and cultural revival in the early 20th century. In the 2000s, Siarhei began teaching and is now a faculty member at the European Humanities University (Vilnius).

Tasks

Vintsuk Viachorka

Topic: The evolution of Belarus’ youth movement in the 1980s: From cultural and educational to political

Lesson based on: An interview with Vintsuk Viachorka; book excerpts and articles

Abstract: The youth movement in Belarus, which was not under the control of the communist party leadership, emerged at the beginning of the 1980s, even predating Perestroika. This movement was first seen as a circle of lovers of Belarusian folklore, as was the case with the “Maistrounia” association. But gradually Maistrounia’s activities diversified, including protecting and studying historical and cultural monuments as well as campaigning for the Belarusian language and education in it. Finally, in 1984, association members defended the construction of Minsk’s first Belarusian theater, which in that context was an act of disobedience. After this, Maistrounia ceased to exist officially.

That said, Maistrounia inspired the development of independent youth organizations throughout the country. The Belarusian youth movement became rapidly politicized by the late 1980s. In 1989 the Confederation of Belarusian Communities (KBS), a coordinating body for the movement, was established. And thus began the movement’s political phase.

1. National youth cultural activity in the early 1980s

Briefly tell the students about the political and cultural situation in the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic (BSSU) in the first half of the 1980s and the importance of the first youth cultural initiatives using the book and interviews:

- Siarhei Dubaviets. Workshop: The Story of a Miracle [B. m.] 2012.

- Interview: Vintsuk Viachorka (00:10 – 8:44).

Maistrounia at the Call of Spring in Zaslauje. April 24, 1982.

Siarhei Dubavets and Vintsuk Viachorka are in front.

Print out and distribute the translation of the book excerpt:

From the book of Siarhei Dubaviets: “This story began on Christmas Eve 1980. Minsk’s Central Square was so hopelessly empty, so cold and dark that the sudden crowd of carolers falling into this cold, dark emptiness seemed either a stupid joke, because they weren’t joking then, or a violation of the unity of time and place, or a real miracle. The Belarusian idea, which true patriots kept and cherished both underground and in their souls for decades, broke out to win more and more supporters until there were enough of them to struggle for national Belarus.

Perhaps it was a small revolution, because nothing like it had happened before. But in this revolution, there was no direct protest, confrontation or destruction. It was a positive, enthusiastic and not quite conscious birth. After all, the students from Belarusian Maistrounia, who went to Minsk’s Central Square, could not fully understand what their actions would eventually lead to. Euphoria filled their hearts.

Perhaps it was a lump of previous generations’ efforts, when the first drop of their dreams, sufferings and work, which now turned into a stream, gathered and eventually became a full-flowing river. The underground existence of the national idea is fragmentary, circles appear and disappear, are born and decline, are destroyed by the authorities. And as soon as the idea comes out of the underground it begins to “conquer the masses” and transforms into a “material force.”

One way or another, Maistrounia became the first public organization, and the Belarusian national movement together with Maistrounia became a public phenomenon, no longer elitist and dissident, but open to all “people from the street.”

Reference (background information for the teacher:

Maistrounia (Belarusian Singing and Dramatic Workshop): a youth arts association from 1979-1984 in Minsk.

It was created by students at Belarusian State University and the Belarusian Theater and Art Institute, though later students of other universities, graduate students and the studying and working youth of Minsk joined. The goal was reviving Belarusian folk rituals and holidays in an urban environment. Maistrounia members learned folk songs, organized Christmas , the Call of Spring and Kupalle (summer solstice) in Minsk, Zaslauje and Viazynka. They also held charity events and gave concerts, lectures and talks.

Maistrounia combined singing and folklore activities with cultural, educational and political activities. It considered aBelarusian folk revival to be the best way to raise national consciousness. In 1983, the “Belarusian School Society” was founded by Maistrounia members Maistrounia and advocated for the creation of Belarusian-language kindergartens and schools. Talaka (volunteer work) became a popular activity at archaeological excavations in Minsk’s Troitsky suburb.

Maistrounia ceased activity in 1984 due to conflicts with the authorities, when members came to the defense of a demolished building that housed Minsk’s first Belarusian-language theater. It was followed by the Uladzimir Karatkievich Youth Club (1985-1986) and Talaka (since 1985).

Ask the following questions:

- Why did Maistrounia choose to work publically instead of privately?

- What events did Maistrounia organize?

- What national holidays were important for your family? What’s the most popular in your country?

- What do you think: did the popularization of folk traditions contribute to the strengthening of national self-awareness in society (its partial decolonization)?

- How did similar cultural activities of youth in the 1980s look like in other countries?

- Were expressions of self-organization like Maistrounia a sign of democratization of Belarusian society?

- Is the topic of preserving folk culture relevant today?

2. "Fathers and children": How did the parents of Maistrounia members react to their children's participation in independent cultural activities?

Briefly tell the students about the demographic changes that occurred in Belarus during the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s: Belarus became an urbanized country with a large urban population. In 1976, Belarus’ urban population exceeded the rural population for the first time). But the majority of residents had their roots in the Belarusian countryside.

Print out and distribute this translation of the book excerpt and let the students watch the interview:

Interview with Vintsuk Viachorka (8:50 – 11:30).

From the book written by Siarhei Dubaviets: “From whom did each of us inherit a passion for Belarusian culture in our own way? As a rule, not from our parents. Parents are busy people; they saw us exclusively from a social perspective. So Maistrounia members had conflicts with their parents.

Most often, the miracle of Belarusian culture came from grandmothers who didn’t abandon their rural culture and saw us, their grandchildren, from a more timeless perspective.

The Belarusian village was still alive, and women there were the primary custodians of traditions, culture and language. Our village grandmothers told us fantastic stories, so close to our muffled genetic memory, that everything turned upside down in the child’s soul and he began to search for his human identity in the city. And it wasn’t there…

How is this transfer of culture happening today, when there are almost no traditional villages left? For city dwellers, Belarusian culture can be passed on to grandchildren only when it is passed on to children. And for this, parents must see their children from a more timeless perspective. In other words, parents should also take on the role of grandmothers, acting as custodians of traditions, culture and language.

In this sense, it is easier for the former members of Maistrounia, because they managed to build their bridge from a fairy-tale village to the current urban reality. But the transition of each Maistrounia member took place in its own way.

Ask the following questions:

- Has there always been mutual understanding between the participants of Maistrounia and their parents?

- How important was the connection with the small family of their ancestors for the new city dwellers?

Educational Game: “National Revival and Different Generations”

Divide the students into groups of 5-6. You will organize a discussion on the question of the relationship between different age groups in Belarus during the 1980s in the context of growing interest in national culture. Divide the students into groups of youth, parents and grandparents. Based on the information just heard, these groups must justify their approach to social processes surrounding Belarus’ youth and cultural environment in the 1980s. They must express the aspirations and fears of these different demographic groups.

3. How did youth movements become politicized in the late 1980s and early 1990s?

Briefly tell the students about the political situation in Belarus and the USSR at the end of the 1980s, as well as about the unfolding Perestroika processes and the simultaneous deepening of the socio-economic crisis.

The teacher is invited to familiarize themselves with the reference literature, and students are invited to watch the interview:

Use:

Democratic opposition of Belarus (1956-1991). — Mn.: Archive of Recent History, 1999 (https://slounik.org/153746.html)

Civil movements in Belarus. Documents and materials. 1986-1991 / Compiled by P. Tereshkovich, V. Lebedev. Moscow, 1991. Section IV. (https://static.iea.ras.ru/books/Guboglo/004.pdf; http://old.iea.ras.ru/books/04_BEL/190120040000.htm )

Interview with Vintsuk Viachorka (13:20 – 19:10)

Reference (print and distribute to students):

The Confederation of Belarusian Communities (KBS)/Confederation of Belarusian Youth Communities was an independent social and political youth association in 1989-1990. It included youth clubs, societies and communities whose goal was the national, cultural and democratic revival of Belarus, also concerned with its sovereignty. It was announced at the confederation meeting on January 14-15, 1989, at the Second Free (General) Council of Belarusian Communities in Vilnius.

The illegal group “Independence,” which was created after Maistrounia closed down in 1984, decided to further develop the movement in legal cultural forms. It explicitly aimed at politicization. In February 1985, the group held a meeting of youth from Minsk, Gomel, Brest and Navapolatsk. There they decided to promote the creation of social and cultural youth organizations with the aim of developing them into a national movement. The following years saw the creation of youth associations like “Talaka,” “Tuteyshiya,” “Svitanak,” “Agmen,” “Nashchadki,” the Rock Club “Nyamiga” (Minsk), “Talaka” (Gomel), “Pakhodnia” (Grodno), “Krynitsa,” “March” and the Rock Club (Novopolatsak), “Uzgorye” (Vitebsk), “Krai” (Brest), “Povyaz” (Orsha), “Run” (Lida), “Syabrina” (Vilnius), “New Moon” (Polatsk) and others. Their main activities from 1985-1989 were educational, the revival of national holidays, archaeological and restoration work, the protection of historical and architectural monuments, the creation of Belarusian classes and schools, the declaration of the Belarusian language as the state language and holding rock festivals. Among their largest initiatives were mass, politicized celebrations of “Kupalle,” the summer solstice, a Belarusian-Latvian ecological-patriotic water protest rally against the construction of the Dzvina-Daugava-87 hydro plant station in Daugavpils (April 29 – May 3, 1987); the ecological expedition “Pripyat-88” (May 1988); working with the memory of victims of Stalinist political repressions (November 1, 1987); rallies in Minsk in defense of historical buildings of the Upper City (March 20, 1988), in Kuropaty (June 19, 1988), near Minsk’s Eastern Cemetery (October 30, 1988) and publically raising questions about the return of historical symbols (August 1988).

Since 1989, KBS has published bulletins: “Community,” “Revival News” and “Student Thought.” In 1990, KBS was integrated into the Belarusian Popular Front as a coordinating body. Some communities stopped their activities while others renewed their numbers and continued their activities. In 1990, KBS activists formed the Association of Belarusian Students.

15.01.1989, II General Sejm of the KBS, Vilnius. Vintsuk Viachorka is the first on the left.

Ask the following questions:

- Was the politicization of youth movements inevitable in the late 1980s?

- What forms of political and cultural activity did youth communities use in the late 1980s and early 1990s?

- Is the influence of youth association activities in the 1980s felt today?

- How can the youth movement look and function nowadays?

Siarhei Chareuski

Topic: How the Belarusian National-Cultural Revival of the 1980s Began

Lesson based on: An interview with Siarhei Chareuski, articles and book excerpts

Abstract: In the mid-1980s, Belarus was one of the most industrialized and urbanized republics of the USSR. Minsk held a dominant position: in 1985, 10 million people lived in Belarus, of which about 1.5 million lived in Minsk. Being the capital and largest city of the BSSR, it was predominantly Russian-speaking. The Belarusian language occupied a very modest, formal place in the city’s cultural landscape. One could regularly hear “trasyanka” (a mixed Belarusian-Russian dialect) spoken among the population, but Russian was the language of the administration, economic structures and universities. Publicly speaking or performing in literary Belarusian was considered acceptable only for a narrow portion of the intelligentsia. This way, Belarusian’s official public status was demonstrated, although in fact it was isolated in a kind of cultural bubble. At first glance this is completely unusual, but in the mid-1980s, even before perestroika (“restructuring”) officially took hold in the USSR, interest in Belarusian and national culture began to appear among the youth of industrial Minsk. Informal and creative youth organizations (“Maistrounia,” “Talaka”) emerged. This cultural revival eventually became one of the driving forces of various political and social processes from the late 1980s to the early 1990s.

1. Belarusian in the BSSR (“Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic”) during the 1980s

Briefly tell the students (discussion participants) about the status of languages in the BSSR in the 1980s using the article “The Formation of the Belarusian Language at the Current Stage” by Ales Bialatski (The Situation of the Belarusian Language at the Current Stage, 1983) (https://vytoki.net/?news=00038810) and the book Native Language and Moral and Aesthetic Progress by Aleh Bembel (https://kamunikat.org/rodnaye-slova-i-maralna-estetychny-pragres-bembel-aleg), published in London in 1985 (second edition: 2024).

After the teacher’s information, watch the interview with Siarhei Chareuski (15:00 – 18:10).

Additional sources:

From Ales Bialiatski’s article: “Let’s talk about Belarusians in the city. Fifty five percent of Belarusian children currently live in cities. And even if the child’s father or mother knows and speaks Belarusian, the child himself does not think of it as their native language. This starts from kindergarten, as not a single city teacher speaks Belarusian, the native language of the children she works with.) Then there’s the cinema, cartoons, books and, finally, school. Everyone speaks Russian! Let’s take the Gomel region. Gomel city has about 400,000 inhabitants, Mazyr about 100,000, Rechytsa and Svietlahorsk have 60,000 each, and Zhlobin, Ragachou and Kalinkavichy each have 40.000. About twenty percent of residents in these cities are not Belarusians. Which means that about 600,000 in these cities are Belarusian. Is there at least one Belarusian high school in these cities? No. This is terrible.

I simply cannot understand why it’s considered natural to belittle and neglect the native language. Who’s supposed to benefit from this? And why is everyone silent? We are one people!

In Russian schools, Belarusian is taught 3-4 hours a week. This is just enough to teach students to write “I” instead of “И” and teach them to distinguish “Yanka Kupala” (a Belarusian folk festival) from “Yakub Kolas“ (a Belarusian writer). And children do not want to learn Belarusian for understandable reasons. It’s not used in the city. No one speaks it and no institution uses it as a working language. It’s useless. Except for the radio, which no one listens to, and TV advertisements, which no one watches. Belarusian is not actually the state language of Belarus. The attitude towards it in schools is about the same as towards Latin, a dead language.

Most young people from villages who come to the city to earn money have to quickly “relearn” to speak Russian. That’s because speaking Belarusian implies that you’re from the village or that you’re backward and uncultured. It is interesting to watch how a mother walks into a bookstore, looks at the children’s books, wrinkles her nose and says: “There are only Belarusian ones; there’s nothing to buy.” It is scary. But from the outside, everything looks good. The BSSR is a member of the UN, Belarusian writers receive state awards, “Pesniary” and “Vierasy” are known throughout the country. All this is good. And people… disappear. But what about the BSSR Ministry of Education, or in the end the government? Are they all the same? Will Belarusians really disappear as a people in 50 years?

I want to scream. But will anyone hear? Each of us must do everything in our power. Belarus must finally wake up. We must gather at least what is left because in time it will be too late. Belarusians, understand that you are a people like other peoples.. That you have a richer history, culture, literature and your own customs.”

Aleh Bembel, Belarusian dissident Mihas Kukabaka and Belarusian journalist Antanina Khatenka

From Aleh Bembel’s open letter to the General Secretary of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev (1987): “I was forced to write the book Native Language and Moral and Aesthetic Progress due to my deep concern for the state of the Belarusian language in today’s Belarus. Of course, I cannot say how perfectly I managed to implement my plan. But I, to the best of my ability, tried not to deviate from the principles of complete truth and openness, which, in the words of Pravda [the central newspaper of the Communist Party), is ‘a sword that heals wounds.’”

Title page of Aleh Bembel’s book

Optional material for teachers:

Excerpts of an interview from Aleh Bembel’s book Native Language and Moral and Aesthetic Progress:

(Woman, 30, Russian, English teacher at Minsk University)

“After all, what happened to Belarusian intellectuals [in the early years of the USSR]? Naive, open, gullible: almost all of them were killed…

…Georgians, Lithuanians, they won’t speak Russian without an accent, although they can speak perfectly. But Belarusians are ashamed of their accent. Russian boys who are 17 years old, silly guys, they start laughing. Our language is funny to them, and Belarusians, their peers, for some reason feel awkward. I show them how many Belarusian words, as well as English ones, have a Latin root (article, palace, lover) and they somehow start to be proud…

…This feeling of false shame begins even in kindergarten. Our Vania is the only child in the group who read a poem in Belarusian on March 8th. The teachers turned on him and asked, “Why, what’s the point?”…

(Man, 30, Belarusian, art critic)

“The most dangerous thing is the school problem. In essence, fundamentally negative attitudes towards the language are formed in kindergarten and school. The absence of the native language leads to spiritual underdevelopment and has a powerful effect on the psyche. People start disbelieving in their own strength. Disbelief in the strength of one’s people, nation, culture.”

(32, Belarusian, artist)

“I studied poorly at school. And the most difficult subject was Russian. And I remembered this. The same thing happens now with my child: every day a little enemy of national culture comes from kindergarten.”

(Born in 1925, Belarusian, mathematics teacher)

“In my opinion, it seems that teachers who teach like this are not doing it quite right. I don’t know how to put it better. The textbooks are in Belarusian, the teacher studied at a Belarusian pedagogical institute, but he teaches in Russian. The school is considered Belarusian. But let him put himself in the shoes of a fourth or fifth grader who finished their first three grades in Belarusian.

It seems that this issue requires a thoughtful solution coming from the higher authorities, because this is widespread in the Minsk region.”

(Woman, between 30 and 40, Polish-Belarusian, hydrobiologist)

“Belarusian… Well, I don’t know any other language like it. It’s not costumes or anything else but language that reveals the soul of the people. Recently, an old lady started swearing on the bus. Someone stopped her from getting off at her stop. The whole bus listened with great pleasure! And we were very sorry that she got off at the next one.”

(Man, 30, Belarusian, art critic)

“The idea that the Belarusian language is ‘ugly’ or ‘unoriginal,’ this is again the result of opinions imposed on us at an age when we couldn’t think for ourselves.”

Ask the following questions:

- What was the situation of the Belarusian language in the BSSR in the 1980s?

- Did the Belarusian intelligentsia and urban youth realize that the Belarusian language was in crisis?

2. How to organize a Belarusian disco in Minsk in the mid-1980s?

Briefly tell the students (discussion participants) about discos as a form of youth leisure in the 1980s. This form of activity was then under the control of the Komsomol. Briefly introduce the audio equipment that was used in the 1980s: reel-to-reel tape recorders (“bobbinniks”).

After the introduction, show the interview with Siarhei Chareuski (20:00 – 25:00).

For teachers: Due to the unavailability of records from abroad, and the poor quality of cassettes, reel-to-reel tape recorders (“bobbinniks”) became the favorite equipment for Soviet music lovers. That said, bobbinniks were difficult to operate and maintain. Loading the film, cleaning the heads and setting up recording sessions took a lot of time, and the reels themselves took up all the free space in the apartment. But the film itself was wide and allowed for high-quality audio storage, and the tape recorders themselves had a wide range of speeds.

For students: According to Siarhei Chareuski’s memoirs, he recorded music from his friends’ “Kometa” tape recorder, and at school they played it through the speakers of an “Astra” tape recorder.

Soviet reel-to-reel tape recorders from the 1980s

Kometa-212 stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder

One of the most common tape recorder models in the USSR. It was produced in Novosibirsk.

Astra-209 stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder

The “Astra” from Leningrad had a good design and their technical characteristics were above average. These recorders were always a standard in any large radio and electronics store. Astra-209 stereos had speakers and even a remote control, and it cost less than 300 rubles. This was more than two months’ salary on average, but it was an average-priced tape recorder.

Ask the following questions:

Was it easy to organize discos in Minsk during the mid-1980s?

How important was it to organize Belarusian-language discos for young people in the Russified Minsk of the 1980s?

Educational game: Organize a Belarusian disco in Minsk during the 1980s

Students are divided into groups of 5-6 people with the goal of organizing a disco. They must draw a poster and explain how they will invite people. They should also discuss technical aspects, like obtaining or copying music recordings or finding tape recorders and amplifiers. It’s very important that they mention the names of Belarusian rock bands from that time who could be played at a disco.

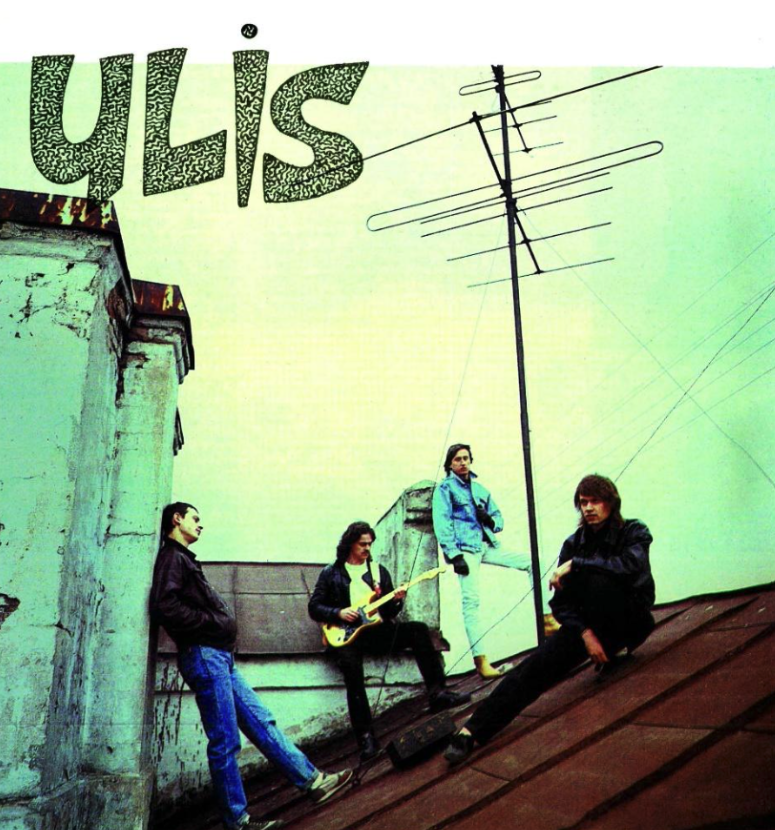

3. What Belarusian-language rock bands existed in Belarus in the mid-1980s?

Briefly tell the students about the 1980s Belarusian rock movement. Use the book “Praz-rok-pryzmu” by Vitaut Martynenka and Anatoly Myalguy . (https://kamunikat.org/praz-rok-pryzmu-martynenka-vitawt-myalguy-anatol ) & Interview with Siarhei Chareuski (21:21 – 22:20).

The first Belarusian-language rock bands of the 1980s (information for printing and distributing to students). The teacher can ask students to listen to individual songs

Bonda was one of the first Belarusian rock bands. They played from 1980 to 1989 and inspired bands like Krama, Rokis, ULIS and The Little Blues Band.

Mroya was formed in 1981 by Minsk Art College students. The band plays hard rock with elements of punk and traditional Belarusian music.

ULIS was a rock band formed in Minsk in late 1988 by former members of Bonda.

Ask the following questions:

- Why was the emergence of the 1980s Belarusian-language rock movement important for Belarusian culture?

- Why do you think 1980s rock musicians started performing their songs in Belarusian?

- Why do you think 1980s rock music in Belarus became a symbol of creative freedom?

- Do you think the songs of 1980s Belarusian rock bands had political relevance?

4. What forms of cultural youth activity could exist in the mid-1980s? (Based on the example of the club "Talaka")

Briefly tell the students (discussion participants) about the Talaka youth club of the mid- to late 1980s.

Use the materials:

Democratic Appearance of Belarus (1956-1991). – Mn.: Archives of the New Historical Collection, 1999 (https://slounik.org/153746.html )

Civil Movements in Belarus. Documents and Materials. 1986-1991 / Authors P. Tereshkovich, V. Lebedev. Moscow, 1991. Section IV. (https://static.iea.ras.ru/books/Guboglo/004.pdf ; http://old.iea.ras.ru/books/04_BEL/190120040000.htm )

After the introduction, watch the interview with Siarhei Chareuski (0:35 – 7:51).

Print and distribute the following:

Talaka Club

Talaka (Minsk) was an independent youth organization as well as a historical and cultural association in the mid-to-late 1980s. It was founded in fall 1985 as a club for protecting monuments and became a successor to Maistrounia. Talaka became the largest and most influential informal organization up to 1989. Talaka brought together about 60 members, but many more participated in meetings and tolokas (volunteer work). Talaka worked on several fronts: restoration and archaeological work, protecting historical and architectural monuments, fighting to create Belarusian classes and schools, nature expeditions, cultural/educational activities and reviving folk holidays. They organized annual celebrations for Kupalle (summer solstice), Kaliady (folk Christmas), Klikanne vesny (the arrival of spring), which soon became traditions once again. On March 20, 1988, Talaka organized a rally to defend Minsk’s historical Upper Town. This was the first public rally in Belarus in the late Soviet era.

The March 20 Talaka rally to defend Upper Town. On the podium is Talaka’s chairman, Siarhei Vitushka with speaker Siarhei Chareuski. Photo by Mikola Sasnouski.

Talaka organizes Kaliady celebrations. Minsk, 1989. Photo by Aleh Grushetski.

Talaka organizes the Gukannya vyasny (“crying spring”) festival with games for young people. Minsk, Gorky Park, 1990. Photo by Aleh Grushetski.

Ask the following questions:

- What activities did Talaka association organize?

- Do you think such cultural and educational activities can be effective for developing civil society?