Georgia: A rocky road to the nation-state

The late ’80s to early ’90s were years of drastic change for Georgia. The end of socialism, political liberalization, the USSR’s fall, and state independence fundamentally altered Georgia’s trajectory. These tumultuous times, heightened by ethnic tensions and economic instability, left a lasting impact on Georgia’s social, economic, and political structures.

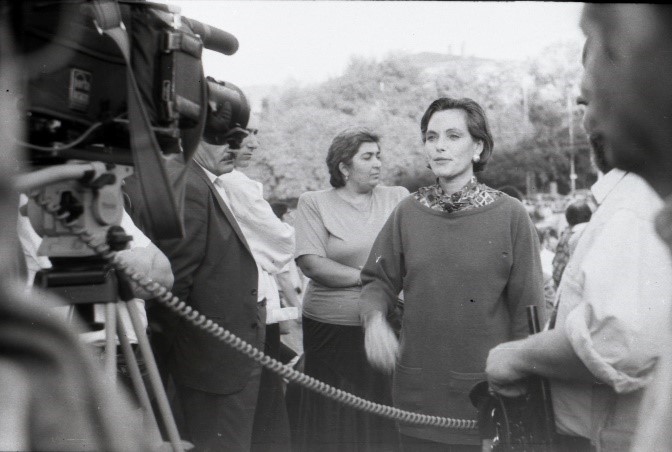

Figure 1: Mass demonstration and civil encounter in the street of Tbilisi, 1991. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

Different realities on the periphery of the USSR

After Gorbachev announced “Perestroika” Georgian society changed profoundly. Key elements of these changes were a rapidly developing economic crisis and deficit in everyday life, political amnesty which allowed political prisoners, already legendary leaders of Anti-Soviet groups, to return home, as well as the urgent escalation of national/ethnic hate in nationally diverse areas, particularly in Abkhazia.

Georgia’s position on the periphery of the USSR had meant that everyday social and economic realities differed vastly from those within the more centralized republics of the USSR. Corruption was extremely dominant in the Soviet state and communist party system, and this, combined with the mass robbery of State goods, clan networks, symbiosis of Party, underground economy and criminal elites, and exclusive ethnic nationalist sentiments drilled in through education and culture as a tool of ensuring loyalty to the regime, created a very complex everyday reality. The disproportion of wealth between cities and rural areas, particularly the non-official privileges of the urban social elites, the ease with which “intelligentsia” state security and police members and underground “kings” could break the law and become incorporated in corruption network, meant that the urban populations could enjoy marginally more freedoms, even though this was a fragile comfort at best and unsustainable at worst.

Ethnic diversity and the critical situation of minorities in the late USSR

At the end of the 1980s, around 55% of the 5,4 million population was living in cities and 45 % in rural areas. The main national groups were Georgians, Armenians, Russians, Azerbaijanis, Ossetians, Greeks, Abkhazians, Ukrainians, and Jews. On its territory two Autonomic Soviet Republics were located – the Abkhazian ASSR and Adjarian ASSR – as well as one autonomic district of South Ossetia. According to the communist ideology and totalitarian system, other than ethnic minorities, official identification of other minorities was troublesome – the state was officially atheistic, gender and sexual diversity was punishable, society and healthcare system was oppressive towards people with disabilities, and the dominant ideology blocked any attempts at creativity that deviated from the official framework. As a heritage of Stalin’s approach, all “traditional” religious institutions since 1943 were openly controlled and administered by the Soviet state, parallel to wide infiltration by the KGB. The regime was forcing religious institutions to take part in Soviet foreign propaganda campaigns, calling for the “World Peace” offered by Communist rule.

The first protests in 1988 and inter-ethnic tensions

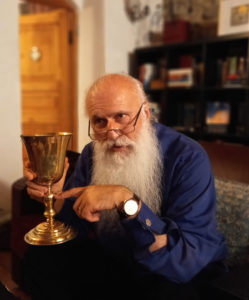

Figure 2: TV Broadcast during the protest demonstration in Tbilisi 1991. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

At the end of 1988, a wave of mass protest against the reforms of the Soviet constitution, which was considered a means of blocking the union republics from leaving the Soviet Union officially, swept over the country. At the same time ethnic tensions worsened irreversibly in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and the Lower Kartli region, over the question of self-determination of parts of the population there on the one hand and independence of the Georgian state from the USSR on the other hand. In April 1989, this ultimately led to mass demonstrations emerging in Tbilisi. The local communist authority, fearing the demand for Georgian independence, called Moscow to interfere and the USSR army and special units suppressed the peaceful demonstrations on the night of April 9th, 1989 by using chemical weapons against civilians.

Figure 3: Mass demonstration and civil encounter in the street of Tbilisi, 1991. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

At the same time, tensions in ethnically diverse regions were deepening into disintegration and confrontation. Extreme nationalist rhetoric from all sides meant that ethnic and religious minorities (Russians, Ossetians, Jews, Armenians, Estonians etc.) either started to flee from the areas of ethnic tension or later were unofficially forced to leave.

Figure 4: Street demonstration in Tbilisi at the end of the 1980s. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

Re-establishing an independent Georgia in 1991

Figure 5: Street demonstration in Tbilisi at the end of the 1980s. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

In the first multiparty elections in October 1990, the opposition block led by Zviad Gamsakhurdia, won the majority. The Supreme council organized a referendum on independence on March 31st in 1991 and an overwhelming majority voted for re-establishing the independence of Georgia, which was then declared on April 9 1991. After winning the presidential election Gamsakhurdia was faced with the challenge to reanimate a collapsing state apparatus and to deal with complex internal and foreign hindrances, having only resources available. The Kremlin backed local paramilitary and criminal groups, and opposition parties launched an attack on the Government’s house on 22nd December 1991. Zviad Gamsakhurdia was forced to leave Georgia. The official dissolution of USSR Georgia spiraled into complete disintegration and the emergence of ethnic wars, which led the country to total disaster and what has been termed the so-called “Dark 1990s”.

Bloodshed and war in South-Ossetia and Abkhazia

At the beginning of 1992, forces organized a coup d’état and declared themselves the “Military Council” made the former foreign minister of the USSR, Eduard Shevardnadze “Head of State.” In 1992, according to an agreement between Shevardnadze and Boris Yeltsin, Russian troops were placed in the contested region of South Ossetia to attempt to settle the tension. That same year, on August 14th, 1992, Georgian military units entered the Abkhazian autonomic republic, in order to prevent its secession from Georgia and suppress Gamsakhrdia’s local supporters too. Armed clashes between Georgian units and Abkhazian paramilitaries, backed by Russian troops, lead to a year of bloodshed and fighting in Abkhazia. It ended in September 1993 when the capital, Sokhumi, fell. Hundreds and thousands of Georgians and other nationalities were forced to leave Abkhazia and thousands were killed or injured. The Abkhazian population suffered heavy losses during the war and the breakaway region was left in social and economic collapse.

Figure 6: Ruins of the Parliament and Government house after the coup d’état in Tbilisi 1992. From the collection of Ani Gagua.

The following collapse of political and civil institutions, the extraordinary authority of the criminal underworld, the dismantling of the economy, war, and humanitarian and refugee crises shocked Georgian society. The majority of the population lost their savings due to hyperinflation and manipulation of state reserves. In 1995, the state finalized their campaign of “privatizing” former Soviet state property. Officially it was considered an opportunity to grant citizens a fair share of state wealth, but within the frame of economic collapse, war and criminal rule, the remaining state wealth ended up being absorbed instead by the minority: the elites associated with ruling political elites and the criminal underworld. Corruption, criminal rule, radicalism, poverty, and social depression became an everyday reality in Georgia.

A long road to rights for minorities

Ultimately, the 1990s made little positive change for those trapped in the vulnerable layers of society. As a result of societal collapse, the wars and failure of statehood, the scale and number of vulnerable groups increased to include the masses of internally displaced people, ecological migrants, and unemployed citizens, who had fallen victim to the failure of Soviet centralized industries. Together with ethnic, religious and sexual minorities they shared complex challenges: ignorance, aggression and isolation. Although an independent Georgia started in the 1990s to adopt legislation guaranteeing equality and social security of citizens, which included the country joining various international frameworks depending on the rights of minorities, in everyday life, the corrupted and failed state mostly was not able nor motivated to implement those values. The only progress in defending the rights of minorities, bringing their voices in mainstream public discourses, was associated with newly formed civil society organizations and the self-organized groups of minorities themselves.

Timeline

-

Founding of the first official opposition group, “Ilia Chavchavadze society” 31.10.1987

-

Protests in Tbilisi commemorate the day of Soviet Russian occupation of Georgia 25.02.1988

-

Mass protest demonstration in Tbilisi against a group of Abkhazians' appeal to become a union republic within the USSR 04.04.1989

-

Suppression of peaceful mass demonstration by Soviet interior forces, special units, and the army; 21 people dead 09.04.1989

-

Violent clashes in Sukhumi, Abkhazian ASSR, between Georgians and Abkhazs due to a dispute over the opening of a branch of Tbilisi State University 14.07.1989

-

First violent clashes in Tskhinvali, South Ossetia, occur when demonstrators from Tbilisi, attempting to enter the city, are blocked by Soviet internal forces and local Ossetian nationalist groups 23.11.1989

-

Opposition block “Round Table for Independent Georgia” wins majority in the first multiparty elections of the Supreme Council of Georgian SSR 28.10.1990

-

Independence re-established: Backed by the majority vote of the population, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, chair of the Supreme Council, declares Georgia's independence in session 09.04.1991

-

After suppressing a demonstration of the Georgian opposition National-Democratic Party, permanent anti-government demonstrations begin in Tbilisi 02.09.1991

-

Coup d’état: Opposition parties and paramilitary groups attack the government house in Tbilisi 22.12.1991

-

Zviad Gamsakhurdia flees to Grozny, Russian Federation 07.01.1992

-

Eduard Shevardnadze, former secretary of the central committee of the Georgian communist party and foreign minister of the USSR, is installed as the "Head of State" 07.03.1992

-

Agreement between Eduard Shevardnadze and President of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, to regulate the so-called “South Ossetian conflict”: Peacekeeping troops, dominated by Russian and North Ossetian battalions, are placed in the region 24.06.1992

-

War in Abkhazia: The self-declared "State Council" sends Georgian military units to Abkhazia 14.08.1992

-

Fall of Sukhumi, the capital of Abkhazia; Russian-backed Abkhazian forces win the war 27.09.1993

-

Georgia joins the “Commonwealth of Independent States'' (СНГ) 03.10.1993

-

Former President Zviad Gamsakhrdia is killed by special forces loyal to Shevardnadze in the Abkhazian mountains 31.12.1993

-

The Georgian parliament adopts a new constitution 24.08.1995

-

Unsuccessful assassination attempt on Eduard Shevardnadze by political elites close to Russia 29.08.1995

-

The controversial privatisation of Soviet state property officially concludes 1995

Eyewitnesses

Tasks

Discussion

Totalitarian regime and Religions

For pupils

Duration: 25 minutes

Priority – for local, Georgian audience. Might be used in international format

Divide into groups and research about religious communities in the soviet union. Present to the rest of the group shortly about each religious community and its status in the Soviet Union.

Listen to the memory of Malkhaz Songhulashvili about who the KGB was trying to infiltrate. Discuss:

- Compare the story of attitudes of modern Georgian state security officers against the Evangelist-Baptist church in 1990’s and Soviet KGB style. Can you notice the difference? Which changes in state agenda can we identify?

- Have you heard about the attitudes of the Soviet regime against religion in your family? Ask your grandparents and relatives about their experience and compare it with knowledge you’ve got during the lesson and discussion.

- Can you notice the difference in approaches against orthodox church and the so-called “Sectas”?

- Why was it important to the Soviet regime to control religious institutions?

Discussion

Escalation of conflicts

For pupils

Duration: 25 minutes

Priority – for local, Georgian audience. Used fragments of the ral histories about the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict contains information/knowledge which is specific and close to the local audience.

Teacher explains theoretic framework of ethnic conflicts:

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group’s position within society. This criterion differentiates ethnic conflict from other forms of struggle.The end of the Cold War thus sparked interest in two important questions about ethnic conflict: whether ethnic conflict was on the rise and whether given that some ethnic conflicts had escalated into serious violence, what, if anything, could scholars of large-scale violence ( security studies, strategic studies, interstate politics) offer by way of explanation. One of the most debated issues relating to ethnic conflict is whether it has become more or less prevalent in the post–Cold War period. Even though a decline in the rate of new ethnic conflicts was evident in the late 1990s, ethnic conflict remains the most common form of armed intrastate conflict today. One of the most debated issues relating to ethnic conflict is whether it has become more or less prevalent in the post–Cold War period. Even though a decline in the rate of new ethnic conflicts was evident in the late 1990s, ethnic conflict remains the most common form of armed intrastate conflict today.

Let’s have a look at a map of the post-Soviet conflict zones.

Divide into groups and explore basic information about each of them and make a short presentation to the other groups.

Discussion

Economy during the transition

For pupils

Duration: 25 minutes

Priority – for local, Georgian audience. Might be used in international format

Watch the documentary footage from 1990’s Tbilisi

Read the quote from the article about “Privatization”

Quote: “…More than 3 000 000 people already received “Voucher”, but only 1 million managed to use it (approx. 33%). In Georgia 20 auctions have been held, where more than 600 companies offered approx. 35 % of their stock papers. Until the end of year there must be 5 special stock auctions to be held, as mass privatization should end by 1996. From the new year there will be additional auctions of those entities, whose stock papers weren’t sold yet – to let the citizens who couldn’t use their Vouchers yet to do it, but as we see according to the current behaviors of citizens, they aren’t too interested in auctions and privatization. On one hand it’s because of lack of information and also the majority of citizens can’t understand the whole system of privatization and prefers just to sell their Vouchers.

Society has the impression that a major part of state property being transferred to the ownership of individuals is done secretly, as newspapers where information about the privatization is promoted is distributed only in the capital city and because of energo-crisis TV and radio channels couldn’t cover the regional areas.

Also, it was said many times, but… People who are hungry, who dream even to buy the daily bread, when they are given Vouchers without preparation and in such a fast manner, they are acting due to the basic instinct. Hungry man couldn’t wait for the dividends after several years and turned to sell his Voucher even for a penny. And it happened today. Because of this the majority of the population is absent from the privatization. Accordingly, the privileged, rich part of society uses such an opportunity and officially declares its behaviors as a patriotic step, in reality absorbing and stealing the people’s property.”

Use the cartoon as an input for discussion

Inscription says: State industry. We are waiting for the law about Privatization. We are starting a trade.

Ask questions:

- What do you see in the video which speaks about the economic condition of citizens?

- What do you think is the best way to separate a shared property?

- How would you use “Voucher” (your symbolic share of state property) – sell or invest in industry, when you are an average citizen, with the same condition of life – demonstrated in video?

- What do you think, who was able to buy a state property in the 1990’s?

- Can you identify the results of problematic “Privatization” in today’s life?