Photographer Dmitry Borko looks back on the events of failed Soviet coup attempt in August 1991, as does Elena, who recognized herself in one of Dmitry’s photographs.

Photographer Dmitry Borko has worked in the media since 1987 and for the Nezavisimaya Gazeta (The Independent Newspaper) in 1991. He has been an eyewitness for significant events of that period and captured many of them on film. He is the author of the book «1991/1993.»

ГКЧП

Between August 18 and August 21 1991, a group of Soviet officials calling themselves, “State Committee on the State of Emergency,” or GeKaChePe, attempted to depose Mikhail Gorbachev, then president of the Soviet Union. They sought to prevent the signing of a new treaty between the Soviet republics that they viewed as a threat both to their own power and that of the Soviet Union.

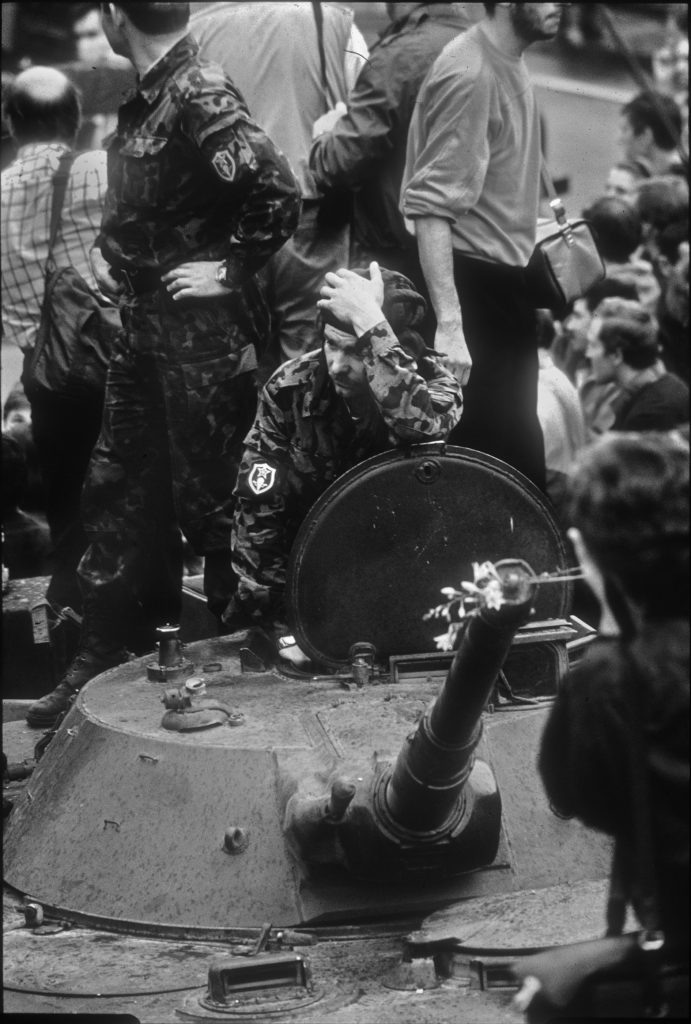

The leaders of the coup were hard-line members of the CPSU, opposed to Gorbachev’s reforms and his devolvement of much of the central government’s power to the republics. They succeeded in putting Gorbachev under house arrest, after which they declared a national state of emergency and demanded that he resign from leadership of the Soviet Union. Large numbers of troops and tanks were deployed to Moscow.

The attempt was, however, quickly met by civic and political resistance. Opposition politicians, including Russian President Boris Yeltsin, publicly denounced the coup d’état, and it eventually collapsed on August 21 1991. Large anti-communist demonstrations continued in Moscow and what was then called Leningrad. People in Moscow gathered at the Lubyanka square at the then-headquarters of the KGB. Following the coup’s failure, the large statue in Lubyanka Square of Felix Dzerzhinsky – founder of the Soviet secret services – was torn down on the evening of August 22 to the cheers of the protestors present.

The effects of the coup, however, cannot be underestimated. Although restored to power, Gorbachev’s authority had been irreparably undermined. He resigned as General Secretary of the Communist Party following the coup, and the Supreme Soviet dissolved the Party and banned all Communist activity on Soviet soil. Boris Yeltsin, on the other hand, managed to expand his power. Just a few weeks later on September 6, the government recognized the independence of the Baltic states, and, over the next three months, one Soviet republic after the other declared independence. By the end of the year, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. Thus, the coup attempt was immensely significant to the course of history, and marked the pivotal point of the beginning of the transition process in the Soviet Bloc countries.

Documenting the event

In August 1991, Dmitry Borko spent many days and nights in the centre of Moscow, a place filled with numerous troops deployed for the attempted coup. The centre of resistance to the coup was the White House, the parliament building first of the RSFSR and then of independent Russia. The building was surrounded by barricades, with democratic politicians and Boris Yeltsin, the elected president of the RSFSR, inside the building. As Dmitry wrote: «Many of the participants in those events are still alive. And the issues that they tried to solve are still relevant today. These photographs do not provide answers – they just show you how it was.”

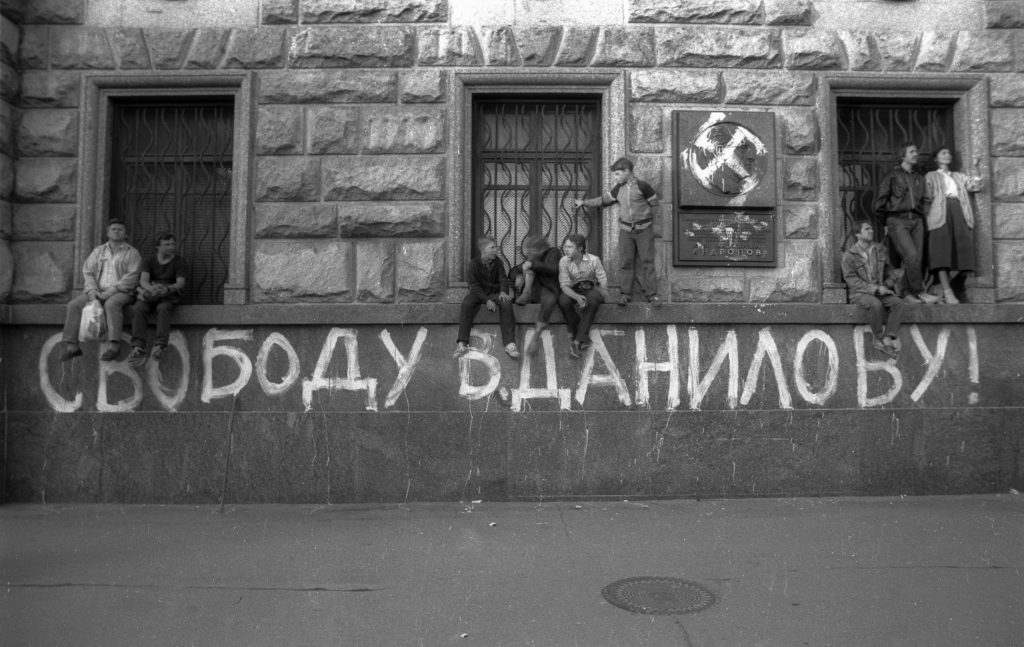

One of Borko’s photos from August 22, 1991, shows a group of young people upon the window ledge of the Lubyanka building of the KGB, waiting for the tearing down of the monument to Dzerzhinsky. Elena is one of those pictured, alongside her husband Tom. Until the publication of a recent article, she had no knowledge of the existence of this photo.

Transition Dialogue took the opportunity to talk with Elena about her story and her feelings about that time, and to ask the author of this photo, Dmitry Borko, how it all happened.

The lack of fear

Dmitry Borko: On August 22, I «scanned» the centre of Moscow. People were rallying, discussing events in various places. I saw a column of demonstrators walking from the White House through Manezhnaya to the Lubyanka square and joined them. So many people eventually gathered at the Lubyanka that they filled the entire square. They rallied on, and it all ended with the monument coming down. On the basement of the facade of the KGB building, someone had written «Freedom to Danilov!» in large letters. Danilov was a member of the Democratic Union and an associate of Novodvorskaya, who was arrested before the events. And the bas-relief with the portrait of Andropov had been painted over with a white swastika. There were some young people standing on the plinth nearby. And that’s what I captured.

Many years later, a woman found me on Facebook. It turned out that she had been captured in the picture with her now husband. I sent her the picture in full resolution, and we exchanged memories of that day.

TD: What do you remember about this day and the moment in the photo, what was going on?

Elena: At that time, we were just newlyweds and we still lived in two different cities, Tom in Moscow and I in Leningrad [now St. Petersburg]. Tom had spent a few nights in the streets around the White House and I had spent the same nights in St. Petersburg, my TV running with the audio muted and the radio with the sound turned up to make sure that I didn’t miss out on any information. Then I suddenly decided that I couldn’t wait any longer. So, I went to the Central Moscow Railroad Station in St. Petersburg and bought a ticket to Moscow from a military officer who had decided to postpone his trip to Moscow because of the situation. When I arrived in Moscow, Tom met me at the station, holding a portable radio in his hands. Others who had come to the train station grouped around him and we listened to the news that some of the coup members had just fled to the airport Belbek. Nobody knew where Belbek was or what any of it meant. In the next few days, everything became clear. Tom had then taken me to where the events took place. At some point during that trip, we were at the window of the Lubyanka KGB building awaiting the removal of the Dzerzhinsky monument. We spent about two hours there, but we eventually left [before the statue was actually removed].

TD: Why was this photo captured and why has it remained important to you?

Dmitry Borko: Because of its connected symbols. I was struck by the fact that the swastika, a much hated symbol for the Russian people because of its embodiment of fascism, had been combined with the symbol of Soviet power, the KGB, as if demonstrating that the regime that had just collapsed was just as unacceptable and hateful.

TD: Is this photograph still significant for you today?

Elena: We came across this picture very recently, less than a year ago. We saw it in Facebook post from a popular writer and blogger – Lev Rubinstein – and it came as quite a shock to me. I was so glad that this picture exists. We all wanted the best for our country. At that point, we thought that it would take 10, or at most 20 years for Russia to be more or less like any other European country. We truly believed in that. I guess it was appropriate, given our age at that time.

TD: What else is memorable about that day?

Dmitry Borko: The symbols. The demolition of Felix [Dzerzhinsky], the red, white and blue of the Russian flag, which had been banned, flying over the White House. And Lubyanka Square. Not just the swastika, perhaps there was another image that looked even stronger. The main entrance of the building does not face the square, but is behind it, facing the Dzerzhinsky grocery store. Whilst the rally was taking place on the square, I walked with a small group of people walked around the building and saw people in suits hurriedly coming out of the entrance, looking around themselves, holding tightly onto stuffed briefcases or sports bags. Then the Volga drove up and some of the boxes were loaded into it. And the Muscovites were standing across from them, pointing fingers at them and laughing: «The rats are running away, they’re trying to hide their secrets!» Their free laughter and the lack of fear of these fleeing little men, who not so long before could have terrified anyone, was the most powerful symbol of that day.

Of course, this also indicated carelessness: we shouldn’t have let them take the documents away, this hydra was more tenacious than we thought. It was probably worth levelling the citadel to the ground, after all, as many people wanted then. But at that moment, all else felt unimportant, and I remember that feeling as if it was yesterday.

TD: How do your personal and public perceptions of this photograph align? Has anything changed in the aftermath of the photo?

Dmitry Borko: Not very long ago, two opposing outlets (first, just before its closure, the “New Times“ and, more recently, “The Project») published this picture of the Lubyanka Square. Yet the swastika on it was blurred out of fear of sanctions under the new anti-extremist laws. In both cases, I demanded either they remove the retouching or remove the photo from the article altogether. The funny thing is that soon after the publication of this picture, both outlets were forced to close. Not because of my photo, of course. But I think the story is enlightening of my perceptions.

TD: What happened in your life, both before and after this picture?

Dmitry Borko: For me, almost nothing has changed in this time. I worked in the independent press before the photograph and continued to after until there was practically no independent press left. These days, the value of my shots has not decreased in the slightest. It’s just that I was a little mistaken in my expectations, that’s all, but that is my own problem. I would say that today these memories and this story seem to me much more significant than it did then: it is something that both gives strength and strengthens faith in oneself and other people in today’s very troubled times. I have heard from many that there was disappointment, but there was not. Going out onto the streets back then was a completely conscious and independent decision for me, for my friends and, I am sure, for many other people. And all this talk about «manipulation of politicians,” «cheating,» «deception» is for those who do not believe in themselves and do not respect themselves. It had been “explained” to us long since and very diligently for this exact purpose: so that in no case would we be able to respect ourselves.

Elena: At that point in time, we had already applied to graduate school in the US. A friend of ours had mailed our applications from a different country so that it would avoid KGB surveillance and we were waiting on the outcomes. In 1992 we left for graduate school and have lived in the US ever since. Tom is a professor of physics at a major US public university, and I am now a software engineer.

TD: Is there a main picture for you, the «significant image» of August 1991?

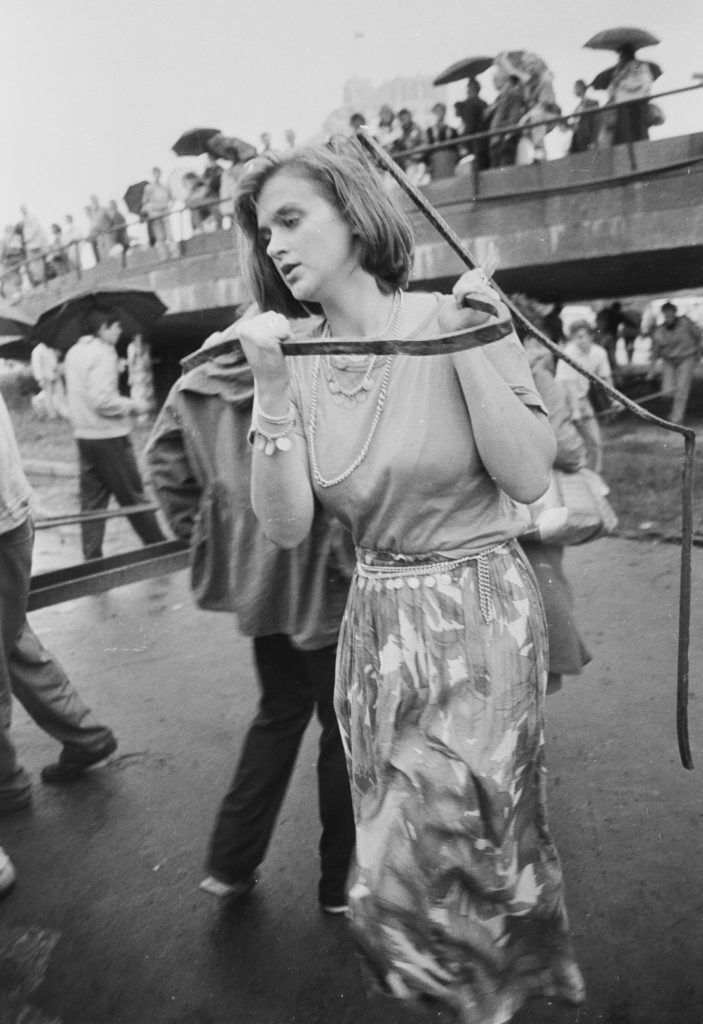

Dmitry Borko: I don’t think there is one for me. There are, as I said, several symbolic shots. These are of tanks on Novy Arbat and a photographer taking pictures of them with a bicycle. The photographer is not me, but it could be me or anyone else. It was the first appearance (not counting the parades) of tanks in Moscow. It was not very scary yet. In two years, Muscovites will understand that the army in the city is no joke, and that it cannot lead to any good. There’s also the above-mentioned shot from the Lubyanka (as well as Felix [Dzerzhinskiy] with a noose around his neck). And the girl in a smart dress, constructing a barricade. Yes, it’s certainly hard to list all of the “significant images” for me.

A selection of photographs by Dmitry Borko, August 19–22 1991, Moscow.