* Header image. Figure 1: Armenpress. An Armenian youth raises his fist, inspired by the Karabakh movement, from the balcony of the government building as a sign of emerging independence.

Armenia: Overcoming adversity and profound loss

The period from 1988 to 1998 in Armenia was a crucible of change, marked by the Karabakh movement, the Spitak earthquake, and the aftermath of the USSR collapse. Amidst adversity, the nation navigated towards independence, profoundly shaping its socio-economic and political landscape.

The Karabakh movement paved the road for independence

Transition in Armenia was largely shaped by the Karabakh movement and the following war, Spitak Earthquake, long-term blockade and significant socio-economic downfall.

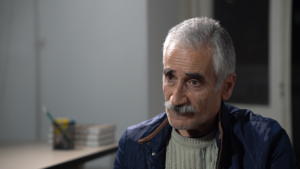

Figure 2: Armenpress. An Armenian woman votes in a referendum on Armenian independence. September 21, 1991.

Launched in 1988, the Karabakh Movement was a broad-based civic movement in Armenia and mostly Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast advocating for the transfer of Karabakh from the neighboring Azerbaijani SSR to the Armenian SSR. Growing into a popular democratic undertaking, the movement’s leadership, the “Karabakh Committee”, eventually became a political party, the “All Armenian National Movement” (ANM), that won the majority vote in 1990 parliament (The Supreme Council), first multi-candidate (though not multiparty) elections, introduced as part of Demokratizatsiya (Democratization) policy under Gorbachev’s Perestroika. The ANM declared Armenia’s independence from the USSR on August 23, 1990, which was followed by a referendum for independence on September 21, 1991, and the consequent election of the ANM leader, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, as the first president of Armenia.

Armenia in the USSR: Rich in education, science, and engineering

By the end of the USSR, Armenia was a highly industrialized and urbanized country, with over 70% of its population of 3 287 677 (1989 census data) living in cities. Armenia also had one of the most advanced science and technology sectors supporting the industry. While the science mostly served the Soviet military-industrial complexes, its development also resulted in the establishment of a rich tradition in research, particularly in natural sciences such as physics, biology or chemistry, and ensured strong government support to promote education in science and engineering in Armenia. However, Armenia’s economy was closely tied with the USSR, with 95% of its external cooperation with the USSR, the highest among the union republics.

Therefore, the industry, as well as the industry-linked science and technology sectors could not survive without functional ties with other Soviet Republics.

Decline and crisis after the Spitak Earthquake in 1988

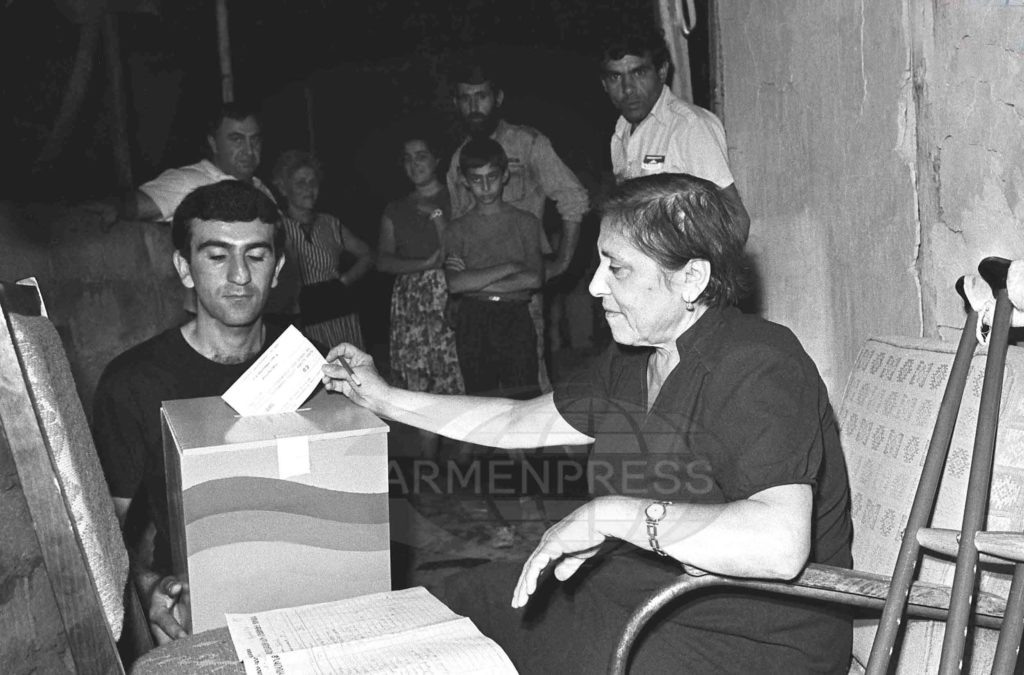

Figure 3: Sputnik. The Church of Christ the Saviour in Leninakan after the earthquake in Armenia on 7 December 1988.

Even before the independence, Armenian industry has sharply declined and the country has experienced a major blow to the economy. First, the Spitak Earthquake of December 7, 1988 not only resulted in a death toll of 25,000, 530,000 people left homeless and thousands of disabled, but it also destroyed 1/3 of country’s industrial capacity. Then, the ANM embarked on speedy political, legal and economic reforms aimed at transitioning from one-party political system and centrally-planned economy to a liberal democracy and market economy. Armenia was among the first Soviet republics to initiate privatization of state enterprises as early as in 1992, and also one of the first to carry out redistributive land reform, whereas most of the agricultural sector in Armenia shifted to individual production and the large collective and state farms ceased to exist. By the mid-1990s one third of agricultural land was privatized.

The darkest years 1991-1994: Energy crisis and war on Karabakh

Figure 4: Armenpress. Stepanakert in 1992.

A major blow to the Armenian economy during the transition was the energy crises resulting mostly from the economic blockade imposed by Azerbaijan and Turkey. The bulk of energy supply in Armenia came from the Metsamor nuclear power plant, which provided roughly one-third of the country’s generating capacity. After the Chernobyl disaster there were concerns regarding its safety, which grew into panic raised by protests organized by the Green Party of Armenia after the devastating Spitak earthquake. As a result, the Metsamor Power Plant was shut down in 1989. After the country’s independence and as soon as the war started, Turkey and Azerbaijan closed their borders with Armenia and put a fuel embargo on the country. At the same time, Azerbaijan blocked the natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan that passed through its territory, thus cutting off about 90% of the natural gas supply to Armenia, while the supply from a new gas pipeline, built in 1993 through neighboring Georgia, was regularly interrupted by acts of sabotage. Between 1992 and 1996, customers suffered through several of Armenia’s brutal winters with little more than two hours of electricity per day. The energy crisis ended only when Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant Unit 2 was restored in October 1995, making it the only reactor in the world that was restarted after closing.

More than 500.000 displaced people due to the war with Azerbaijan

Figure 5: Armenpress. Armenian soldiers during the first Karabakh war.

The Karabakh conflict resulted in war (1991-1994) and human losses (over 5,000 dead and 20,000 wounded), as well as an influx of over 360,000 ethnic Armenians from Azerbaijan and outflow of over 160,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis to Azerbaijan. Not only many refugees have hardly escaped pogroms and were not able to bring any of their belongings, but they were mostly from big industrial cities of Azerbaijan, such as Baku and Kirovabad (currently Ganja). In contrast, Azerbaijanis of Armenia were predominantly rural inhabitants. The Government decided to settle the newcomers in the former Azerbaijani villages of Armenia. This created additional problems, as the Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan were in most cases industrial workers, engineers, teachers, service workers etc. and did not know how to cultivate land or handle livestock. Moreover, many were Russian speaking and Russian educated and could not read or write in Armenian, while according to the Language Law adopted on March 30, 1993, the official language of the newly independent Armenia was Armenian, and it was hard to find a job or to help a kid with school if one did not know Armenian. These issues, coupled with the overall harsh socio-economic situation in the country, created additional vulnerabilities for the refugees. As a result, a lot of refugees have eventually left the country and many who stayed are still living in hard conditions.

As a result of the war, blockade, energy crises and the collapse of the Soviet economic network, most industries shut down, which led to rising unemployment and economic paralysis. Armenia’s GDP contracted by about half in 1992, and by 1996, 55% of the population were living below the poverty line. Armenia also had one of the highest unemployment rates in former USSR during the transition. A comprehensive study on Armenia by UNDP estimates that about 50% of all working age adults (25-49 years of age) were without formal employment by 1998.

Inequality grows as new social strata are forming

Figure 6: Armenpress. Bread queues in the 1990s

New social strata formation and growing inequalities were also part of the transition logic. As in many other post-Soviet states, most political, social, economic and civil institutions had collapsed. As a result, the majority of the population lost its savings and was impoverished. At the same time, some people suddenly became very rich utilizing the corruption schemes during privatization, or gaining wealth at the expense of the Karabakh war. Similar to the neighboring Georgia and many other post-Soviet republics, these new economic elites were closely linked to the ruling political elite, and some of them also had ties to the criminal structures. Eventually, this led to the formation of local oligarchs closely linked to the ruling political parties, resulting in further polarization of the society, and marginalization of different groups.

Thus, while the independence was a long-standing dream for many in Armenia – a country still traumatized by the 1915 Genocide and further worn out by the USSR’s policy of arbitrarily drawn borders with Azerbaijan and thus susceptible for national independence movements – the 1990s hardly brought any positive change for the vulnerable and disadvantaged. Moreover, the above-described series of extraordinary events, i.e. socio-economic collapse and dysfunctioning of state institutions, war and humanitarian crisis, growing inequalities resulted from what many believed unfair privatization and consolidation of country’s wealth in the hands of few linked to the ruling political elite, had a direct impact on almost every Armenian citizen and led to the enormous increase in the number and scale of vulnerable groups. These included most of the population of the earthquake zone, masses of unemployed as a result of the collapse of the Soviet centralized economy, thousands of disabled from the earthquake and/or the war, hundred of thousands refugees from Azerbaijan, rural population near the Armenia-Azerbaijan border who could not engage in farming due to the shootings and unstable security situation. As a result, there was a mass outflow of people from Armenia in the early 1990s. According to the estimates more than 610 000 people, or one out of every five citizens, left the country and did not return in 1992-1994.

Only after the Ceasefire in 1994 Armenia was able to slowly stabilize the situation and start rebuilding its economy which in return helped to ease the social and political crisis.

Timeline

-

Start of Karabakh Movement 20.02.1988

-

Spitak Earthquake 07.12.1988

-

Shutdown of Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant 02-03.1989

-

Last Soviet Elections in Armenia where the representatives of the All-Armenian National Movement were elected to the Supreme Council 20.05.1990

-

Declaration of Independence 23.08.1990

-

Referendum for Armenia’s Independence 21.09.1990

-

First Karabakh War 1991-1994

-

Economic blockade emposed by Azerbaijan and Turkey 1992-1995

-

Signing of Karabakh Ceasefire 12.05.1994

-

Resignation of Levon Ter-Petrosyan, first president of Armenia 03.02.1998

-

Armenian parliament shooting, a terrorist attack on the National Assembly that among others killed the then Prime-Minster Vazgen Sargsyan and Parliament Speaker Karen Demirchyan 27.10.1999

Eyewitnesses

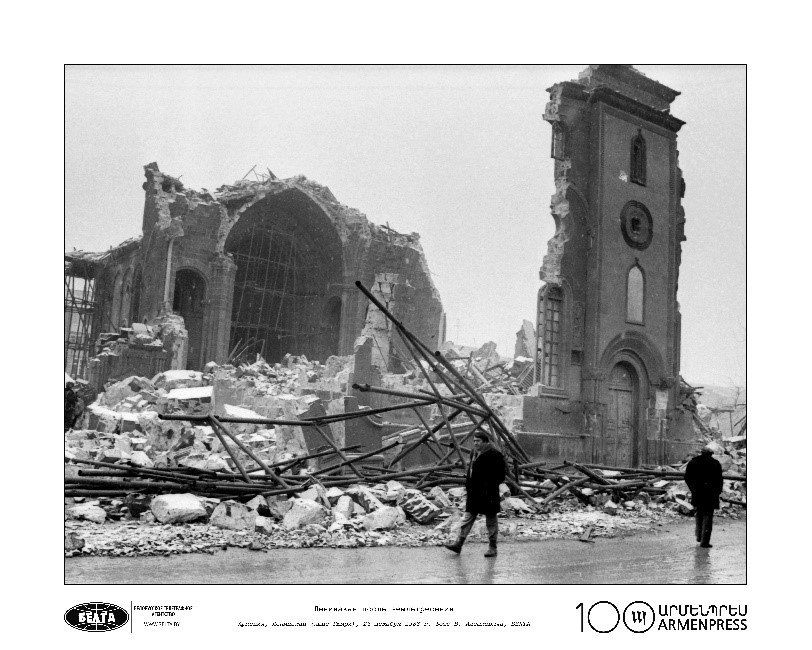

Topic: Soviet Dissidents and the Transition

Duration: 60 minutes

Target group: High School and 9th grade students, up to 25

Materials for the task: internet, projector, flipcharts and markers

Step by step description of the assignment:

Step 1, 27 minutes: Listen to the account of Vardan Harutyunyan

Step 2, 15 minutes: divide participants into groups of 4-5 and let them discuss/answer the following questions:

- What are three main things you learned from Vardan’s account

- What were the main ideas of dissident groups in Armenia for which they were persecuted by the Soviet state? Were those groups marginalized and vulnerable? Why and how?

- Which dissident ideas/notions became prevalent/mainstream ideas during the Karabakh movement and set the ground for the construction of Armenia’s independence? Why and how?

- Do you think the status of political/civic dissidents have changed during the transition? How?

Step 3, 15 minutes: Presentation and discussion of group work.

Topic: Science and Industry during the Transition

Duration: 60 minutes

Target group: High School and 9th grade students, up to 25

Materials for the task: internet, projector, printed reading materials

Step by step description of the assignment:

Step 1, 20 minutes: Listen to the account of Sirarpi Arustamyan

Step 2, 20 minutes: divide participants into three (3) groups, provide them with small/short readings from the module on transition in Armenia (attached). Ask them to recall relevant parts in Sirarpi’s account that illustrate/are linked to the historical context described in the reading. Let them answer the following questions:

- How was Sirarpi’s life before and during the transition?

- What were the main changes that happened to her personally? How are those related to the broader context described in the text?

Step 3, 20 minutes: Presentation and discussion of group work.