THE ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF TRANSITION TAUGHT THROUGH

THE ACCIDENTS OF BIRTH GAME

Examples from Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, and Poland

Authors: Vedrana Pribičević & Bistra Stoimenova

I. Overview

This lesson plan uses storytelling and characterization to describe the economic and institutional landscape of communism/socialism and explains how three main pillars of transformation – stabilization, privatization, and liberalization – aimed to create modern market economies in post-communist countries in Europe. It uses the concept of “accidents of birth” to illustrate and compare how the everyday lives of various inhabitants of transition countries changed as the economy transformed. With the help of economic data, we tell the story of the fates of workers, entrepreneurs, peasants and landowners from Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland and East Germany who were all born in 1971 and experienced a communist regime, and both transition and post-transition economies during their working life.

II. Objectives

- Understand the different pre-transition institutional systems across different transition economies.

- Understand the key aspects of transformation: privatization, liberalization, and stabilization.

- Be able to identify the key the failures of transition – on a local, national, and transnational level while distinguishing between the winners and losers of transition, both internationally and intra-nationally.

III. Key concepts

Communism/Socialism – Umbrella terms referring to two left-wing schools of economic thought which oppose capitalism; a way of organizing a society in which major industries are owned and controlled by the government rather than by individual people and companies, and economic decisions and the pricing of goods and services are governed or guided by a central government plan.

Market Economy – An economic system in which major industries are owned and controlled by individuals or companies rather than government, and economic decisions and the pricing of goods and services are guided by the interactions of a country’s individual citizens and businesses.

Economic transition – Directed institutional change aimed at transforming an economy from a centrally planned to market economy, consisting of stabilization, liberalization, and privatization.

Privatization – Privatization refers to the transfer of the ownership and control over assets, firms, and operations, from the government or the state to private investors.

Liberalization – The economic processes of loosening government regulation restricting the freedom of private owners to run their business, including government policies that promote free trade, deregulation, the elimination of subsidies, price controls and rationing systems, and, often, the downsizing or privatization of public services.

Stabilization – A government policy or set of measures intended to stabilize a financial system or the economy, usually by employing fiscal and monetary policy to increase economic activity (raise GDP), reduce price inflation, expand employment, and reduce a trade deficit (an unfavourable imbalance in trade between two states).

IV. Key question

How do experiences of the economic effects of transition differ across the countries and social classes of the Eastern Bloc?

V. Step-by-step description of the lesson

Introduction: What is economic transition and why do we need to understand it?

In the broadest sense, transition can be defined as the process a country undergoes to shift its economy from a centrally planned economic system to a free market system. In the language of New Institutional Economics – a separate branch of economic thought focusing on the roles of institutions in explaining emergent economic phenomena – transition can be viewed as a coordinated effort of directed institutional change unmatched in scope and magnitude in human history.

The rise of the economic and political institutions that made capitalism possible were a result of a series of critical junctures. The concept of a critical juncture refers to situations of uncertainty in which the decisions of important actors are decisive in the selection of one path of institutional development over other possible paths. Often, the landscape of the decision space was shaped by purely exogenous events, (i.e., outside of the influence of decision makers), that severely affected the probability of the emergence of certain types of political and economic institutions which we now consider prerequisites for capitalism. An example of an exogenous event creating a critical juncture was the Black Death of 1349 which decimated Europe’s population in a very short period, creating labour shortages which led to the slow, but certain demise of manorialism in medieval Europe as the bargaining power of serfs increased. The resulting institutional change, the Ordinance of Labourers issued by King Edward III, aimed at curbing the soaring wages of workers who survived the plague – albeit being largely ineffective – is considered to be the origin of labour laws regulating relationships between employers and employees. In this sense, the institutions of capitalism evolved over time, but the path was both uncharted and influenced by external factors ranging from pathogens to changes in climate. Transition, on the other hand, was a process with a charted path and desired end result.

The process of transformation entailed a transition from some form of socialism to some form of capitalism. Generally, we can distinguish between two models of transition: the East European model and the Chinese model, with the latter not being discussed at any length in this text. The East European model was centered around reforms which were intended to emulate a system of economic and political institutions as similar as possible to those of Western Europe, as fast as possible. The foundation of the proposed reforms was the establishment of well-defined, private property rights, which are considered an absolute prerequisite for modern capitalism by all mainstream economists. From the standpoint of economic policy, economists favoured the big bang approach to transition, advocating quick reforms bundled together, as laid out concisely by Blanchard et.al (1993). The prescribed policy mix had three main ingredients: stabilization, liberalization, and privatization.

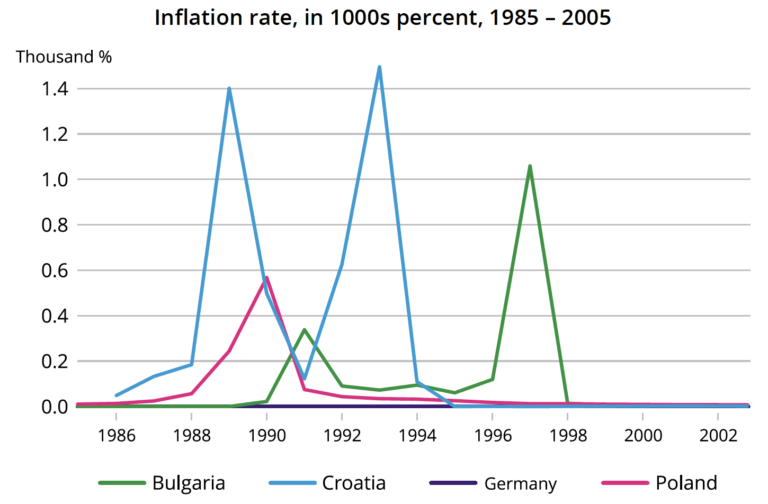

Stabilization emerged as a conditio sine qua non (necessary condition) of further reforms, as all countries of the socialist bloc had for decades endured endemic hyperinflation. For instance, estimated annual inflation in Yugoslavia on the eve of its dissolution in 1990 was 2700%. Hyperinflation distorts the use of money as a medium of exchange, destroys incentives to save, distorts relative prices and is generally considered detrimental to economic growth. The only way to stop hyperinflation was shock therapy, in which a drastic reduction in money supply the only way to dampen the inflation expectations of economic agents. Once hyperinflation was eradicated, complementary reforms of liberalization and privatization could be implemented.

Economic liberalization refers to the loosening of government regulations and restrictions on the economy to encourage private initiative, which in turn enables economic development. This included the removal of price controls, trade liberalization, which entailed reduction or removal of trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas, and other measures aimed at increasing levels of competition. Privatization refers to the transfer of the property rights of enterprises from the state to private entities. The goal of privatization is to increase economic efficiency and better align operations with profit incentives. The policy mix described above is a part of a wider standard reform package dubbed the Washington Consensus, mainly prescribed by the International Monetary Fund to developing countries hit by systemic economic crisis. Structural reforms that included fiscal prudence (tax reform) and deregulation were also an integral part of the transition recipe. These policies met with varying degrees of success and completion across the socialist block. Aid from international institutions, however, was at that point conditional on meeting the aforementioned transition goals.

Accidents of birth in the transition context

Data on the distribution of global incomes between countries shows that inequality between countries is by far the greatest driver of inequality in the world. A recent research paper by Branko Milanovic, one of the foremost global experts on inequality, shows that where you stand in the distribution of incomes across the world is determined largely by where you live, or even by where you are born. In other words, how well off you are before, during and after transition is determined predominantly by where you are born in the Eastern Bloc, and less by how well off you were compared to others in your country. Since a person cannot choose their country of birth, this is called an “accident of birth”.

This lesson plan focuses on four different “classes” of citizens – workers, peasants, entrepreneurs, and landowners, across four countries with a differing economic and institutional arrangement and variants of socialism. The aim is to compare and to contrast not only between classes of citizens in each country, but across countries and over time. Where were the workers initially better off – Croatia or Bulgaria? Where did transition work out better for entrepreneurs – in Poland or Germany?

Characters

Materials required: six-sided dice, pen and paper, projector, or interactive whiteboard

Methods of instruction: Students throw the die to determine their country of birth (1 for Bulgaria, 2 for Croatia, 3 for Germany, 4 for Poland, and 5 or 6 for a re-throw). Students can choose the class to which they belong. They can change country and class when instructed. The teacher reads the introductions to each of the cards to explain the setting and key concepts. Students are given activity cards 1-10 in sequence. Students throw the die, add, or subtract as instructed, and record their results.

UNIT I: HEALTH AND WEALTH IN PRE-TRANSITION ECONOMIES

ACTIVITY 1: Does it matter where you were born in the Eastern Bloc? (10 minutes)

🎯 Aim: Students will be able to understand how country of birth, education, and institutional setup affected individuals at the very beginning of transition, where the variance in these initial conditions affected both the success of transformation as well as public perception of transitional justice.

🗒️ Description: The teacher displays the graphs on Cards 1-3 on an overhead projector and reads the accompanying text while students record their scores.

Card 1: Life expectancy

The term “life expectancy” refers to the average number of years a person can expect to live. Life expectancy is based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die. Differences in life expectancy between countries emerge due to disparities in income, healthcare spending, urbanization, nutrition, education, sanitation, and other forms of public infrastructure directly affecting their standard of living.

Source: World Bank

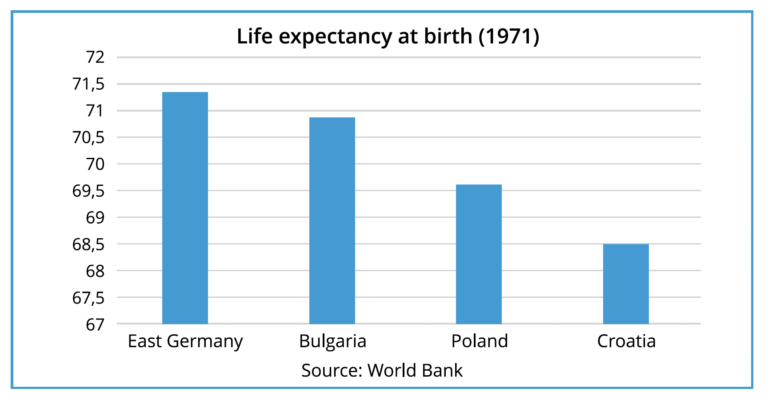

1971 was a good year for technological advancements; microprocessors, LCDs, floppy disks, and email were first invented. The Apollo 15 crew were the first humans to ride a lunar rover on the surface of the Moon. Elon Musk was born in South Africa. What about you? Regardless of where you were born, you were better off than the average inhabitant of Earth whose life expectancy at birth was 59.11 years.

Throw the dice once. Add 4 if you were born in East Germany, 2 if you were born in Bulgaria, 0 if you were born in Poland. Subtract 1 if you were born in Croatia. Life expectancy in the European Union in 1971 was 70.94; if you were born in East Germany where life expectancy is higher than the average inhabitant of the European Union, you get a bonus: add 1 to the total score.

Card 2: Education

Source: World Bank

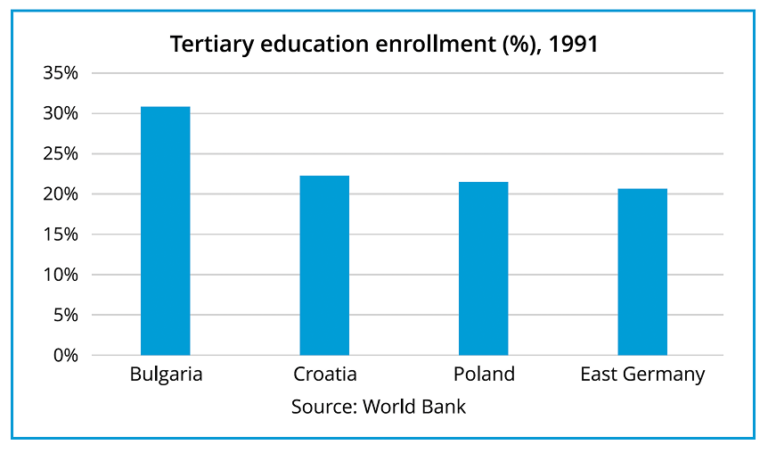

In 1991, you’ve just finished high school and were thinking of enrolling at a university. Three in ten of your fellow pupils who were born in the European Union will start university this year. Will you? To find out, throw the dice once.

If you live in Bulgaria and you roll a 5 or a 6 on the dice, congratulations, you’re enrolled at a university! Add 3 to your score. If you live in other countries and you get a 6 on the dice, congratulations, you’re enrolled at a university! Add 3 to your score.

Card 3: Property rights

Under communism, expropriation was the act of taking privately owned property by the government against the wishes of the owners, ostensibly to be used for the benefit of the public. Property did not cease to exist under communism, however, but took on two distinct forms. The first was known as “the people’s property,” or Volkseigentum, which was based on the collective ownership of the means of production. The second, the issue of private property was trickier. While the term was officially banished as a form of ideological pollution, one’s own belongings were delicately referred to as “personal property” instead. Personal property encompassed the objects and possessions designated in the 1936 Soviet Constitution – and in their equivalent constitutions across Eastern Bloc satellites after 1945 – as embodying the so-called “satisfaction of material and cultural needs”, such as consumer goods and property items produced, bought, inherited, won, or given. Not surprisingly, the legal presence of personal property in socialist life was a source of great concern for communist authorities.

Socialist housing, St. Petersburg. Photo by Damian Entwistle, under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Poland was the only country of the Eastern Bloc which did not have largescale land expropriation. If you are a Landowner in any other country, subtract 2 from your score.

If you are any other occupation other than Landowner, toss the dice and add the result to your score. Croatia was the only country to allow private property of land and real estate, so add 2 if you live in Croatia.

ACTIVITY 2: Comparing fates across the Eastern Bloc I (3 minutes)

🎯 Aim: Students will be able to compare and to contrast their own positions vis-à-vis peers from other countries and/or classes before the start of transition.

🗒️ Description: The teacher pauses the game to establish an intermediate ranking and asks students from each country for their scores and classes, then draws up a scoreboard on the board and briefly comments on the rankings, letting students reflect on their progress as well.

UNIT II: THE TRANSFORMATION TO A MARKET ECONOMY

ACTIVITY 1: The three pillars of economic transformation (10 minutes)

🎯 Aim: Students will become familiar with the three main pillars of transformation: stabilization, liberalization, and privatization.

🗒️ Description: Before the next round, the teacher instructs all Landowners to add two points to their total score before continuing, as private property rights are created and sometimes restituted (given back to the original private owner), at the start of transition. The teacher displays the graphs on Cards 4-6 on the overhead projector and reads the accompanying text while students record their scores.

Card 4: Stabilization

Macroeconomic stabilization is a condition in which a complex framework for monetary and fiscal institutions and policies is established to reduce volatility and encourage welfare-enhancing growth. Achieving this condition requires aligning currency to market levels, managing inflation, establishing foreign exchange facilities, developing a national budget, generating revenue, creating a transparent system of public expenditure, and preventing predatory actors from controlling the country’s resources. It also requires a framework of economic laws and regulations that govern budgetary processes, central bank operations, international trade, domestic commerce, and economic governance institutions. Stabilization of the economy is a prerequisite for economic growth. Empirical evidence shows that creating an environment that is conducive to higher rates of investment can reduce the likelihood of violence, while economic growth has a positive correlation with job creation and higher living standards. Monetary stability involves stabilizing the currency, bringing inflation and foreign-exchange rates to levels consistent with sustainable growth, promoting predictability and good management in the banking system, and managing foreign debt. The primary authority is usually an independent central bank that controls or stimulates the overall economy by manipulating the money supply and interest rates, within the parameters of monetary policy.

Hyperinflation is a term to describe the rapid, excessive, and out-of-control general price increases in an economy. Hyperinflation has several consequences for an economy. People may hoard goods, including perishables such as food, because of rising prices, which, in turn, can create food supply shortages. When prices rise excessively, cash, or savings deposited in banks, decrease in value, or become worthless since the money has far less purchasing power. Consumers’ financial situation deteriorates and can lead to bankruptcy. Also, people might not deposit their money in financial institutions, leading to banks and other lenders going out of business.

Tax revenues may also fall if consumers and businesses can’t pay, which could result in governments failing to provide basic services. If you live in Croatia, you’ve experienced two bouts of hyperinflation. Subtract 1 from your score. If you live in East Germany, you’ve experienced stable prices. Add 1 to your score. If you are a worker in Croatia, Bulgaria, or Poland, you may be able to renegotiate your paycheck to account for inflation. Throw the dice once and subtract 1, then add the remainder to your score.

Card 5: Liberalization

Economic liberalization encompasses the processes, including government policies that promote free trade, deregulation, elimination of subsidies, price controls and rationing systems, and, often, the downsizing or privatization of public services. During transition, government policies were redirected to follow a noninterventionist, or laissez-faire, approach to economic activity, relying on market forces for the allocation of resources. It was argued that market-oriented policy reforms would spur growth and accelerate poverty reduction. Trade liberalization is the removal or reduction of restrictions or barriers on the free exchange of goods between nations which leads to higher trade openness and higher economic growth.

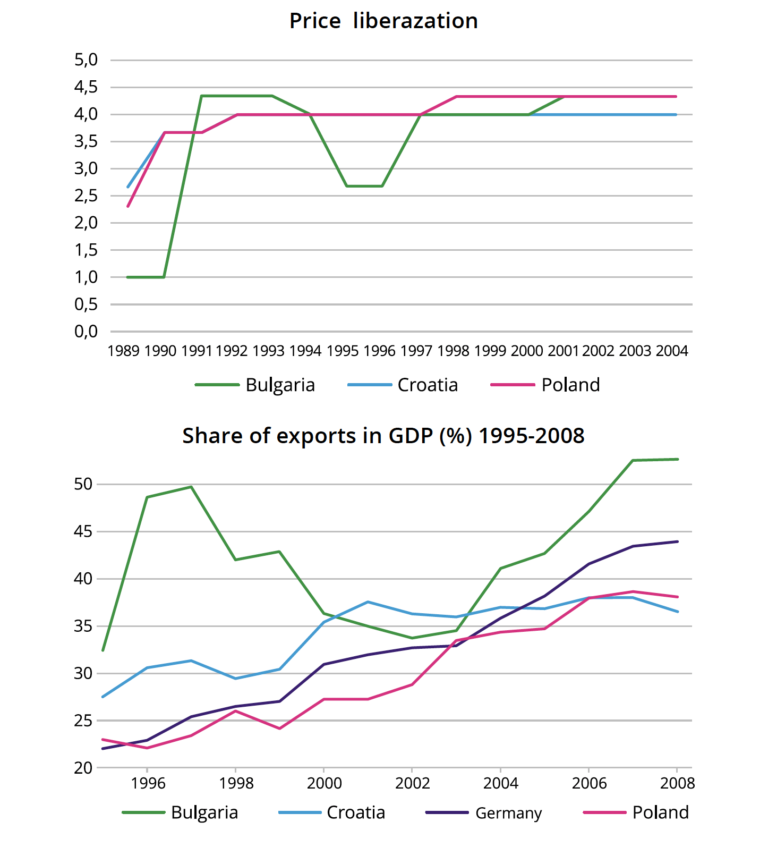

Price liberalization was relatively rapid in all countries, reaching the levels of liberalization of industrialized capitalist countries by the end of transition. Everyone add 1 to your score. The share of exports in GDP rose substantially as the economy became more open.

Rising exports present new opportunities for entrepreneurs. If you are an entrepreneur, throw the dice once and add it to your score. Openness also includes freedom of movement and labour. If you are a Worker, you can now change country if you like.

ACTIVITY 2: Comparing fates across the Eastern Bloc II (3 minutes)

🎯 Aim: Students will be able to compare and to contrast their own positions vis-à-vis peers from other countries and/or classes during the period of transition.

🗒️ Description: The teacher pauses the game to establish an intermediate ranking once again and asks students from each country for their scores and classes, then draws up a scoreboard on the board and briefly comments on the rankings, letting students reflect on their progress as well.

UNIT III: DID TRANSITION DELIVER A BETTER TOMORROW, AS IT PROMISED?

ACTIVITY 1: Failures of transition (12 minutes)

🎯 Aim: Students will understand the main failures of transition stemming from bankruptcy, an increase in unemployment, an increase in economic inequality and rampant corruption.

🗒️ Description: The teacher displays the graphs on Cards 7-10 on the overhead projector and reads the accompanying text while students record their scores.

Card 7: Bankruptcy

One of the ultimate goals of economic transformation in transition countries, and its Achilles heel, is the selection of viable firms among newly established undertakings, as well as identifying which of the former state-owned enterprises (SOEs) can be successfully reorganized to survive the free market environment. Bankruptcy is a market-driven legal process which solves that problem. There are three possible reasons why a firm may be forced to declare bankruptcy. The first one is as a result of a long-term structural circumstance. For example, in which the allocation of assets is considered to be economically inappropriate (meaning, the enterprise which currently owns the asset lacks the labour or complementary assets required to begin to exploit it at all, or to exploit it over the long term). The assets are usually industry-specific, and bankruptcy is a mean of re-allocating them (meaning, an investor buys the asset from the administrator of the insolvent enterprise, at a price lower than the now bankrupt enterprise was prepared to sell it for). The second reason for bankruptcy is of a short-term financial nature. The firm has the right structure of assets, but suffers liquidity constraints (meaning, it cannot finance its running costs during the process of production, usually because banks are not prepared to provide short term financial support). This means that even if the firm is viable in the long run, it has to declare bankruptcy in the short run. The last reason for declaring bankruptcy is that the firm has the proper asset and financial structure but is managed badly. Inefficiency forces the firm out of the market as a consequence of unsolved problems in corporate governance.

Gdansk shipyard. Photo by Astrid Westvang under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

From textile industry to shipbuilding, transformed companies in all the selected countries experienced difficulties in adjusting to foreign competition in international markets. If you are a Worker or Enterpreneur, subtract one from your total score.

Card 8: Unemployment

The situation of the labour market in former centrally-planned economies, at the onset of transition, was characterized by full employment, no open unemployment (with the exception of the former Yugoslavia) and an excess of labour demand over supply. However, full employment was achieved at the cost of low wages, with a demotivating effect on workers. Widespread overstaffing (labour hoarding) occurred in many sectors and serious distortions in the allocation of labour in industry contributed to low levels of labour productivity. The economic reforms launched in the wake of political changes were directed at reversing these negative characteristics, while social reforms were aimed at making these changes socially acceptable and fiscally affordable.

Practically overnight, national economies had opened to world markets through the introduction of economic measures that also allowed rapid price liberalization, combined with a strict macroeconomic stabilization policy. The result was a sharp decline in the economic performance of these countries, much steeper than originally expected. Demand for labour collapsed immediately and, after a short lull, employment also started to decline. The transition process was characterized by extensive changes to existing institutions, particularly the creation of private-owned enterprises. These changes resulted in a sizeable reallocation of labor away from state-owned enterprises, some of which was absorbed by private enterprises and some of which resulted in unemployment.

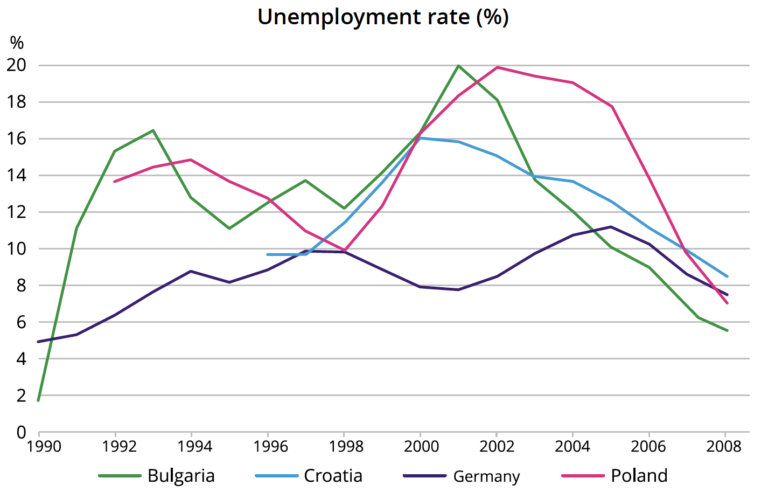

Unemployment sharply increased during transition; firstly, with the initial transformation of the economy and, in the second half of the 1990s, when ex-socialist firms which had been transformed, collapsed. The highest unemployment rates were recorded in Bulgaria and Poland; if you are a Worker in Bulgaria and Poland, subtract 2 from your score. Here you can decide to change your class from Worker to Enterpreneur, Peasant, or Landowner.

Card 9: Inequality

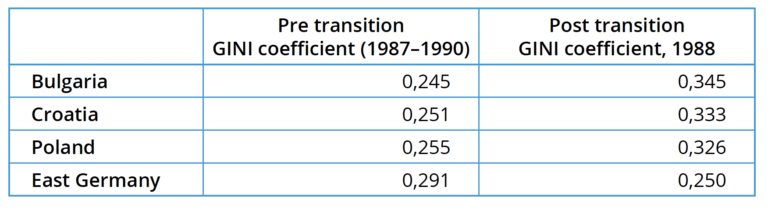

Income is defined as a household’s disposable income in a particular year. It consists of earnings, self-employment and capital income, and public cash transfers; income taxes and social security contributions paid by households are deducted. The income of the household is attributed to each of its members, with an adjustment to reflect differences in needs for households of different sizes. Income inequality among individuals is measured here by The Gini coefficient which is based on the comparison of cumulative proportions of the population against cumulative proportions of the income they receive, and it ranges between 0 in the case of perfect equality and 1 in the case of perfect inequality. A higher Gini coefficient means higher income inequality.

Inequality in the distribution of income during the period of transition increased. The explanation for this increase is rather simple. The social structure before the transition looks as follows; by far the largest percentage of household heads are working in the state sector, where wage differentiation is relatively small and wage levels are moderate. Some heads of household (say, 10 percent) are self-employed. Their average income is higher than that in the state sector, and the distribution of their income is more unequal. Finally, some heads of household (say, 10-20 percent) are pensioners with relatively low income per head and particularly low income differentiation.

During the transition, the large group of state sector workers, with an average income between those of the other two sectors, was divided into different employment sectors. Some workers remained in the state sector. However, others transferred into the private sector, and still others lost their jobs. Whereas 60 or 70 percent of heads of household, before the transition, were state sector employees, with a fairly moderate income differentiation, after the transition, this sector was hollowed out, with some people moving into highly paid private sector jobs and others joining the unemployment rolls. This increased inequality in distribution of income.

Source: UNICEF TRANSMONEE 2005 edition

Apart from East Germany, inequality in income distribution, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has increased during transition. Entrepreneurs and Landowners add one 1 to total score. If you are German, add 1 to your score. If you are a Worker, throw the die once – if you roll a 1,2 or 3, lose one point. If you roll a 4,5,6 gain one point. If you are a Peasant, throw the die once, if you roll a 1,2 or 3, you gain one point. If you roll higher, you gain zero points.

Card 10: Corruption

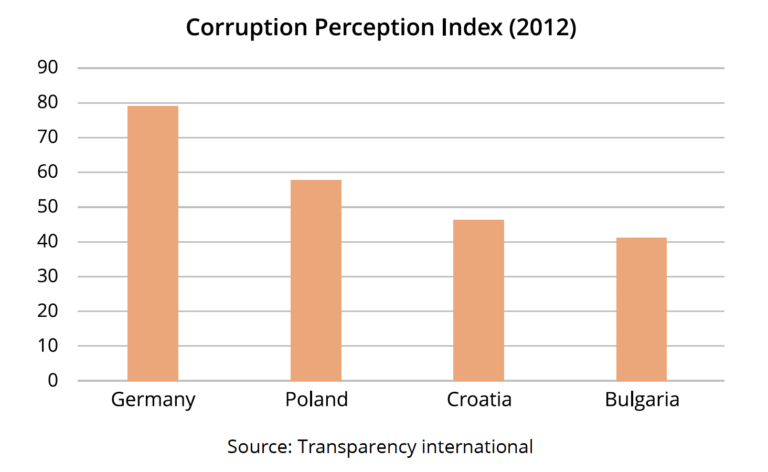

The drastic reform of the economic system has provided great benefits for former socialist states. Despite remarkable economic growth in recent years, however, these countries are face several grave social issues. Above all, the spread of corruption throughout all aspects of civil life is one of the most serious problems. In the communist era, corruption was common and considered by citizens as a necessary evil. It functioned as a social mechanism used to overcome the obstacles created by rigid bureaucratic systems and chronic supply shortages that could affect business operations and everyday activities. In contrast, in the process of the systemic transformation to a capitalist market economy, corruption was motivated by self-interest rather than socially necessity in the former socialist states. This was due to faltering enforcement of the law and weakening police authority, as well as widespread poor living conditions against the background of a culture of abuse which was cultivated in socialist life. Today, in comparison to life under the communist regime, bribing bureaucrats to turn a blind eye to illegal conduct or tax evasion, to procure state-owned assets or receive government subsidies or contracts in an illicit way, has become more widespread in the transition economies.

The corruption perception index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and businesspeople – the higher the index, the lower the perception of corruption. Since it affects everyone in society, if you are from Poland, Croatia, or Bulgaria, throw the die once. If you get a number higher than 3 subtract 1 from your total score.

ACTIVITY 2: The winners and losers in a period of transition (7 minutes)

🎯 Aim:Students will be able to compare and to contrast their own positions vis-à-vis peers from other countries and/or classes after the period of transition.

🗒️ Description: The teacher pauses the game to establish a final ranking and asks students from each country for their scores and classes, then draws up a scoreboard on the board. Students are asked to compare positions amongst themselves but also with respect to the period prior to transition. Questions for discussion are

- Who is better off, and who is worse off after transition?

- What was the main factor which determined differences in your scores?

- Which factor is more significant in determining social welfare; country or class?