PUBLIC MEMORY, DEALING WITH THE PAST, COMPETING MEMORIES

Examples from Bulgaria, Lithuania and Poland

Authors: Bistra Stoimenova, Alicja Pacewicz & Aiguste Starkutė

I. Overview

The lesson focuses on issues related to public memory, dealing with the communist past, and competing memories in three countries: Bulgaria, Poland, and Lithuania. Throughout the lesson students will work with different types of sources that represent diverse perspectives and will use active methods of learning.

II. Objectives

Students will be able to (this is based on the European Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture1):

- Develop their knowledge and critical understanding of the complexity of public memory, dealing with the communist past, and competing memories in society during the period of transition.

- Analyse diverse types of historical sources and identify different viewpoints. • Discuss and express their opinions using concrete facts.

- Develop their skills of listening and observing.

- Develop cooperation skills.

- Encourage civic awareness in issues of transition related to public memory of the past.

- Value democracy and human rights.

III. Key concepts

Public memory – The term refers to the circulation of recollections among members of a given community. These recollections are far from being perfect records of the past; rather, they entail what we remember, the ways we frame it, and what aspects we forget. Broadly, public memory differs from official histories in that the former is more informal, diverse, and mutable where the latter is often presented as formal, singular, and stable.

Civil society – Civil society is an arena of voluntary collective actions around shared interests, purposes, and values, distinct from families, state and profit seeking institutions. The term includes the full range of formal and informal organizations that are outside the state and the market – including social movements, voluntary organizations, mass-based membership organizations, faith-based groups, NGOs, and community-based organizations, as well as communities and citizens acting individually and collectively.

Heritage – The term refers to features belonging to the culture of a particular society such as traditions, languages or buildings that were created in the past and still have historical importance.

IV. Key question

In the post-communist period, what should we do with the buildings and monuments that were symbolic for the former communist regime?

VI. Step-by-step description of the lesson

Time: 80 minutes (2 x 40 minutes)

ACTIVITY 1: Dealing with communist era monuments in public spaces. Ice-breaker activity on the topic of the lesson. (Time: 5 minutes)

🎯 Aim: To introduce students to the topic of the lesson and establish what they already know of this issue.

🗒️ Description: Brainstorming with students

Ask the students if they have heard about communist-era monuments in public spaces; are they still there or have they been demolished? Do they know about street names or public buildings which have been renamed?

If students cannot identify any such cases or can recall only a few individual examples, encourage them to search online. You may also want to display a few photos yourself on the interactive whiteboard. Work together to identify examples of such architectonic objects and places in different spots on local, national, and international levels.

Explain to the students that the debate on the legitimacy of monuments and names from the past is not limited to post-communist countries. Over recent years, such controversies, and conflicts, over symbols of the past have taken place in many countries, including the United States of America, Great Britain and other former colonial empires – with different outcomes. Many monuments are torn down, some of them are destroyed, or transformed and moved to special places such as themed museums and parks or, at the very least, new inscriptions have been added to them explaining these historic figures or events from a different, critical perspective.

You can ask the students to read short descriptive articles on this process (at home), or to summarize the key points and answer one of the questions on which the lesson focuses; in light of all these arguments, should the monuments to controversial historical figures or events be removed, or is this doing a disservice to history, making us victims of it rather than subjects who can understand and engage with it? The teacher can use as additional materials the paper “Monuments to historical figures should remain”2.

ACTIVITY 2: Demolition or rebranding? Working with historical sources (Time: 35 minutes)

🎯 Aim: To extract information from historical sources, analysing them critically and constructing arguments for a debate on what should happen to communist heritage in the post-communist period.

🗒️ Description: The class is split into small groups of 3-4 students. Each group works for 35 minutes with historical sources and learns about cases from Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Poland (see APPENDIX – WORKSHEETS 1-3). Students’ groups are analysing those sources looking for answers to the key question of the worksheet: in the post-communist period, what should happen to buildings which were symbolic for the communist regime? The examples from these three countries offer them arguments for both demolishing and rebranding. Students working in smaller groups should develop their arguments based on specific sources.

Note: The annex provides material from Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Poland. You can contextualize the learning materials and use similar activities/questions to analyse the heritage of the communist regime in your respective countries. Students can also search the web looking for public opinion polls and opinions from their own countries. Regardless of the national and cultural context, debates on “demolishing vs rebranding” were always controversial. The public strategies used by authorities in each case were also similar.

For Worksheet 1 (Bulgaria) – Possible tasks and questions (for source 2):

- Discuss the photo of the mausoleum and the comments on it.

- Cluster the opinions that people shared about the photo into two groups: positive and negative.

OR

- What opinions are there on the photo of the mausoleum?

- How did people react?

- Which comments are more common: positive or negative?

- What do you think of this photo?

Possible tasks and questions (source 3 and 4):

- Present the source: type, author, time of creation, topic.

- How is the demolition of the mausoleum presented? Find specific words and phrases in the text.

- What is the author’s attitude to the event described?

- What do people remember about this mausoleum?

Possible tasks and questions (source 5):

- Find words and expressions in the text that reflect the changes in people’s attitudes towards the mausoleum. Underline them once.

- What possible solutions for handling the mausoleum can you find in the written source? Underline them twice.

ACTIVITY 3: Is communist heritage worth preserving? Discussion (Time: 40 minutes)

🎯 Aim: To understand the complexity of public memory when dealing with the communist past and competing memories in society in the post-communist period.

🗒️ Description: As a continuation of the previous activity (2), split the class into pairs. Give the students 10 minutes to discuss in pairs the overall question: is it important to preserve public memory of the heritage of the communist regime after 1989?

Gather as a class and discuss their opinions for 20 minutes. Emphasize the persistence of public memory when dealing with the communist regime and the existence of competing memories in post-communist times.

To encourage participation, teachers can use the “Four corners” strategy. This strategy provides a structure in which students present their viewpoint about a statement or claim. Every member of the class takes part and gives their opinion in the discussion which follows. It can be used several times in a lesson to show changing opinions as more knowledge is gained. It can help students to think through and justify their opinions before a written task. The basic strategy:

- Identify the four corners of the classroom as ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’.

- Give students a statement or assertion and ask them to go to the corner that reflects their viewpoint. Some students may stand between corners and that is OK. It is likely that students will automatically introduce nuance by standing between corners. Do not discourage this but ask students to articulate their thoughts.

- Ask students to explain the reasoning for their choice of position. Give all students a chance to shift if they are persuaded by others’ arguments.

- By articulating their reasoning and hearing the arguments of others, students are able to deepen and broaden their discussion of topics. Students from each corner can respectfully question and challenge the views of those in other corners.

Additional information for teachers:

Bulgaria: Teachers can use the following video materials on the topic of the lesson:

1) Episode 1: Symbols of power: the Mausoleum, State Security and Fear (in Bulgarian, with English subtitles)3. A short film about the Mausoleum with writer Georgi Gospodinov.

2) In the footsteps of a revolution (the whole tour)4

Lithuania: The case of Lithuania – Grūtas park

Monuments from the Soviet era can be treated in different ways. After the restoration of independence in Lithuania, various Soviet sculptures and monuments, especially those depicting communist political figures, began to be rapidly destroyed. The dismantled monuments were abandoned in warehouses, basements, and garages, as no formal procedure was established for the storage of such monuments and there was no clear decision on what to do with such sculptures; whether to demolish them or rebrand them. Some people, especially those who experienced Soviet repression, wanted all the sculptures representing socialist ideology to be destroyed. They feared that preserving such sculptures and monuments might lead to their use in communist nostalgia and propaganda. These people believe that socialist sculptures should not be considered works of art, but only as useless relics of an unpleasant past. For them, the demolition of all monuments marks their liberation from a hated system. Another group of people wanted Soviet monuments to be preserved, kept in a museum, and used as source for teaching history. Formal monuments might still have the status of cultural objects, so destroying them would not have been so straightforward.

In 1998, the Ministry of Culture announced a tender for an exhibition of dismantled Soviet-era monumental sculptures. It was won by a public institution run by a local businessman, Viliumas Malinauskas. During the Soviet era, Malinauskas worked as the chairman of a collective farm. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, he established a successful mushroom and berry business. According to Malinauskas, he never belonged to the Communist Party and did not support the Soviet regime. The idea to establish a park of socialist sculptures – an open-air museum – came to him when he saw the head of a Lenin sculpture lying on the ground in the yard of an art factory in Vilnius. 20 hectares of swampy forest by the village of Grūtas was dedicated to the Open-Air Museum of Socialist Sculptures. It is located near the resort of Druskininkai and 125 km from the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. Preparations for the exhibition started in 1999. The park was officially opened in 2001 and features about 100 different sculptures.

The aim of Grūtas Park is to preserve icons of Soviet ideology and reveal their negative roles. These socialist monuments, removed from their original context, no longer look as majestic as they did before and allow visitors to see works of Soviet propaganda in a different light. However, the Grūtas Park Museum still has an ambivalent reception in Lithuania. Even though the museum is successful and visited by many tourists from all over the world, people who wanted these socialist sculptures to be destroyed criticise the Grūtas Park Museum. They argue that the crimes of the people immortalized in the monuments are not visible in the way those socialist sculptures are exhibited. For them the establishment of Grūtas Park represents a restoration of these Soviet monuments. They believe the Park may encourage nostalgia for rather than rejection of these Soviet monuments and the ideology they represent. As a result, these socialist monuments still perform an ideological function even after the collapse of the system. Young people who have not experienced the Soviet era or foreigners from the West cannot understand the concept of the museum as they do not know the whole context and they perceive Grūtas Park as a museum of Soviet relics, as entertainment rather than a space for education. Thus, removing socialist sculptures and installing them in an open-air museum could be seen as a way to commemorate the socialist past, as well as a questionable means of attracting tourists, rather than a way of reflecting the difficulty of the past experiences they represent.

Poland:

A debate about the material traces of the communist regime in public spaces has been held in Poland as well. Numerous monuments were destroyed, immediately following 1989, as unwanted symbols of the totalitarian regime. This was the fate of the monument to Feliks Dzierżyński, a Polish communist and one of Lenin’s close collaborators. This statue was located on one of the main squares in Warsaw. It was demolished and replaced later by the sculpture of a romantic poet, Juliusz Słowacki.

At its demolition in November 1989, which became a symbolic public event, Varsovians cheered when the statue of “bloody Felix”, having lost its head, fell onto the pavement.

Until recently there were still hundreds of communist monuments standing in Polish towns. Such monuments were meant to be removed under the special Decommunization Act which was passed in 2016. This Act was intended to remove the communist names of roads, streets, bridges, and squares. In 2017, the Polish parliament adopted an amendment, extending decommunization to include, inter alia, monuments, obelisks, sculptures, statues, stones, and commemorative plaques. Local governments had until the end of March 2018 to remove them, after which local governments (voivodes) would undertake the process of dismantling this communist era infrastructure.

Many monuments were demolished or removed during that time, very often despite opposition from some parts of the public or representatives of local leftwing parties. Most often such statues were not destroyed but transferred to other places, like themed museums or open-air ethnographic museums, such as the Museum of the Polish People’s Republic (PPR) in Silesia.5 The “relics of the PPR” from Strzelce Krajeńskie were removed and will find a place in an open-air ethnographic museum in the Surmówka, in the Warmian-Masurian region, north of Poland.6

More information for monuments in Poland: Project “Monuments of Remembrance 1918-2018”.7

APPENDIX

WORKSHEET 1 – BULGARIA

SYMBOLS OF THE COMMUNIST REGIME AFTER 1989: DEMOLITION OR REBRANDING

❓ Key question: In the post-communist period, what should we do with the buildings and monuments that were symbolic for the former communist regime?

- The Mausoleum (the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum) in Sofia, Bulgaria

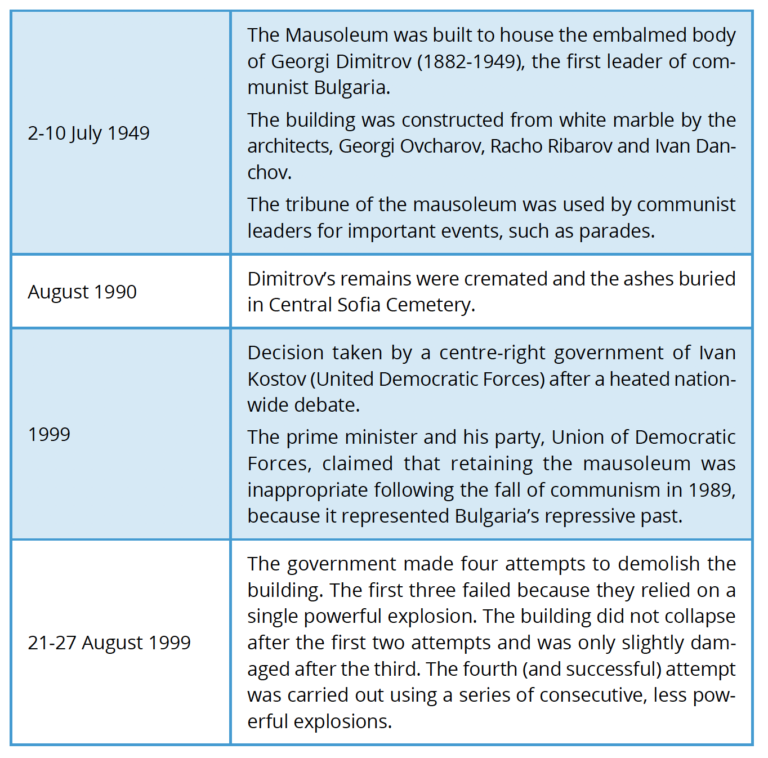

1. Chronology

2. Social media and opinions on the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum, February 2021. Photo of the mausoleum published on Facebook with comments.

Credits: FOTO:Fortepan / AR, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license via Wikimedia Commons.

Selection of comments:

– It could be a museum. Demolishing it doesn’t mean that history has changed.

– The biggest national traitor, Gosho the Plank [Georgi Dimitrov], who gave the Aegean Sea coast to the Greek communists, made presents to Western parts [of Bulgaria, since 1919 they are in Serbia] to Tito and ideologue of the macedonism.

– It is not true! This is the Leader and Teacher of the Bulgarian people!

– And where is the mummy?

– I was four years old, and my granny knew that they will destroy the building and we went there to see him. It was so cold inside this tomb.

– It could be a wonderful sightseeing destination for tourists.

– This should be a museum of communism and it will be full of tourists 24/7 wanting to give their money and see the idiocy of the recent past.

3. Demolition of Georgi Dimitrov mausoleum, 27 August 1999.

4. Goodbye, Mausoleum!

On a suffocating day at the end of August 1999, a group of people have climbed a tribune erected on the square opposite the mausoleum – ministers, deputies, journalists, public figures, in short, the “crème de la crème” of Sofia. One strange detail: everyone has opened umbrellas, black or coloured.

The mausoleum will be demolished today. The spectators wait impatiently, but when the signal is given, they stretch out solemnly. The explosion raises a dense cloud of dust. The audience begins to get excited:

“Impressive!”

“They overdid it!”

“Good thing we were warned to get umbrellas.”

The smoke dissipates and the mausoleum emerges from it. Untouched. A crack between two granite slabs. It will take several days and several explosions, excavators, cranes, and trucks to demolish the building and remove the wreckage. It looked like it was under construction.

Should the mausoleum have been preserved and turned into a monument to communism? With or without graffiti? I do not know. But as they tore it down, I felt the burden of the regime. I felt how long and painful it would be to destroy the reflexes he had bequeathed to us. Only the visible part of the mausoleum disappeared; the foundations and underground corridors remained, like tough roots embedded in the ground. […]

In the place where the mausoleum once stood, the third millennium (after 2001) threw a handful of sequins: cafes and advertising umbrellas.

Several years passed and the mausoleum was forgotten.

Rouja Lazarova*, Mausolée. Paris, Flammarion, 2009, pp. 211-212.

* Rouja Lazarova (born 1968) is a Bulgarian French language writer who has lived in Paris since 1991. She has written several novels and plays.

5. National debate on the Mausoleum

The decision to destroy the Dimitrov Mausoleum was taken after a heated national debate.

The former leader was embalmed and interred in the building in 1949. Mr. Dimitrov’s body was removed from the mausoleum and cremated in 1990, a year after the collapse of communism in Bulgaria.

The fate of the empty building remained a thorny issue.

While ministers said that the mausoleum was an obstacle to redeveloping the capital, some political opponents alleged that the plan was pure politicking ahead of local elections.

One opinion poll found that about two-thirds of the population disapproved of demolition and wanted the monument preserved.

BBC News, World: Europe Communist bastion finally crumbles, 27 August 1999.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/431854.stm

❓ OVERALL QUESTION:

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO PRESERVE THE HERITAGE OF THE COMMUNIST REGIME IN PUBLIC MEMORY AFTER 1989?

WORKSHEET 2 – LITHUANIA

THE CASE OF LITHUANIA – GRŪTAS PARK

❓ Key question: Key question: In the post-communist period, what should happen to the buildings and monuments that were symbolic for the former communist regime?

- Lenin monument in the forest Grūtas Park. This monument used to stand on a high pedestal in the city centre of Vilnius.

Source: personal archive (Aiguste Starkutė)

1. More about Viliumas Malinauskas

Viliumas Malinauskas is a local businessman based near the spa town of Druskininkai. During the Soviet era, Malinauskas worked as the chairman of the collective farm, but after the collapse of Soviet Union, he founded a successful mushroom and berry business. According to Malinauskas, he never belonged to the Communist Party and did not support the Soviet regime. The idea to establish a park of socialist sculptures – an open-air museum – came to him when he saw the head of a Lenin sculpture lying on the ground in the yard of an art factory in Vilnius.

2. Grūtas Park, South Lithuania

See at: http://grutoparkas.lt/en_US/

3. Discussion over the concept of the museum Grūtas Park

The Grūtas Park Museum still has an ambivalent reception in Lithuania. Even though the museum is successful and visited by many tourists from all over the world, some people, mainly former political prisoners, deportees, and dissidents, want these socialist sculptures to be destroyed and criticise the Grūtas Park Museum. Later they were joined by famous academics such as historian Edvardas Gudavičius, linguist and politician Zigmas Zinkevičius, architect Eduardas Budreika, mathematician Bronius Grigelionis and others. The critics of Grūtas park argue that the way those socialist sculptures are displayed doesn’t reflect the crimes of the people immortalized in the monuments. For them, the establishment of the Grūtas Park exhibition equals the restoration of the Soviet monuments. They believe the Park may encourage nostalgia for, rather than rejection of, these Soviet monuments and the ideology they represent. As a result, these socialist monuments still perform an ideological function even after the collapse of the system. “Grūtas Park is already the focus of the humiliation and opposition of many Lithuanians […] The historical memory created in Grūtas park is immoral,” wrote the dissident and Archbishop of Kaunas, Sigitas Tamkevičius, in a letter to the Parliament, Prime Minister and the President. Young people who have not experienced the Soviet era or foreigners from the West cannot understand the concept of the museum as they do not know the whole context and they perceive Grūtas Park as a museum of Soviet relics, as entertainment rather than a space for education. As the researcher Malcolm Miles has observed, “the extent to which the park, with its restaurant and play area, and even a small zoo in plain sight of the signs of power (including a deportation train parked at the site entrance), offers a full day of family entertainment, denotes its appropriation by the tourist industry.” Thus, removing socialist sculptures and installing them in an open-air museum could be seen as a way to commemorate the socialist past, as well as a questionable means of attracting tourists, rather than a way of reflecting the difficulty of the past experiences they represent.8

4. Re-writing history?

Historian and broadcaster, Professor Mary Beard, contends that instead of tearing down memorials to controversial figures, it is “more important […] to look history in the eye and reflect on our awkward relationship to it…not to simply photoshop the nasty bits out.” In a similar vein, some are cautious about the idea of subjecting historical figures to modern standards of moral judgement, and question what good removing a statue of Rhodes will do in a practical sense, as: “Rhodes cannot be expunged from the history of Oxford, Britain and South Africa.”9

WORKSHEET 3 – POLAND

❓ Key question: In the post-communist period, what should we do with the buildings and monuments that were symbolic for the former communist regime?

1. A legal framework for dismantling communist monuments in Poland

According to the provisions of the Act of April 1, 2016, on the prohibition of the promotion of communism or other totalitarian systems, the names of buildings, facilities, and public utilities as well as monuments, may not commemorate people, organizations, events, or dates symbolizing communism or other totalitarian systems. The monuments referring to persons, organizations, events, or dates symbolizing the repressive, authoritarian, and non-sovereign system of power in Poland in the years 1944–1989 are to be removed by 2018. The word “monument” also includes mounds, obelisks, columns, sculptures, statues, busts, commemorative stones, commemorative plaques and plaques, inscriptions and signs. In particular this act applies to monuments dedicated to:

- The Red Army, including the so-called monuments of gratitude, brotherhood, and Soviet partisans.

- Activists of the Polish Workers’ Party.

- The People’s Guard/People’s Army.

- The fight against the Polish Independence Underground after 1944 by the institutions of the Polish People’s Republic (PPR) and the USSR.

- To functionaries of the PPR or communist activists from other countries.

- The Communist Party of Poland.

- Commemorating the construction of buildings on the occasion of an anniversary of the PPR.

The Act does not apply to monuments not displayed for public view; located in cemeteries or other resting places; exposed to the public as part of artistic, educational, collector’s, scientific or similar activities, for purposes other than promoting the totalitarian system; entered – independently or as part of a larger whole – in the register of monuments.10

2. Dismantling the monument in Strzelcach Krajeńskich, 23 March 2019

The “relics of the Polish People’s Republic” from Strzelce Krajeńskie were demolished and will find a place in an open-air ethnographic museum in Surmówka, in the Warmian-Masurian region, north of Poland.

3. Monument to the Soviet-Polish Brotherhood of Arms, Warsaw

Photo by Cezary Piwowarski, under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license via Wikimedia Commons. Source: https://bit.ly/3IR61JD

4. Museum to the PPR in Silesia

5. Division amongst historians

There are two schools of historians in Poland: the first says that such monuments, as evidence of history, should not be removed. The second allows for the possibility of finding more suitable places for such traces of the past. The monument is, of course, a trace of history and deserves respect. Monuments must not be demolished, but this does not mean that they must be accepted indiscriminately. Zygmunt Wożniczka, a historian from Silesia said in a debate on a monument in Zabrze: “So let’s start with who built this monument in the 1980s? It was decided by politicians. It was an expression of the policy implemented at that time, that is, the promotion of friendship and alliance with the Soviet Union. Removing such a souvenir from the city centre is not distorting history. On the contrary. Of course, this is a picture of those times, but it is a false picture. The content of such obelisks not only does not have much to do with the truth, but also does not fit in any way with the traditional Silesian or Zabrze. For many inhabitants of the city or region, they can be even offensive. The Red Army soldiers do not associate them with liberation and brotherhood in arms, but with a plundered and burnt city, with rapes and deportations to the East. With the Upper Silesian Tragedy, which definitely deserves more commemoration in Zabrze.” Paweł Czechowski from an online Histmag portal has a slightly different opinion on a similar monument in Czeladź, also a Silesian town: “Would I handcuff it, destroy it, annihilate it? Have we razed the Auschwitz camp to the ground, or have we made it a sad and painful, but also important place of remembrance of these terrible times? The same should be done with monuments – a good solution is to add plaques explaining the historical context in which the monuments are placed. Then, instead of a pile of rubble, we have an important lesson that a given monument was not an expression of social enthusiasm but, for example, something imposed from above by the regime.”11

6. In defence of monuments

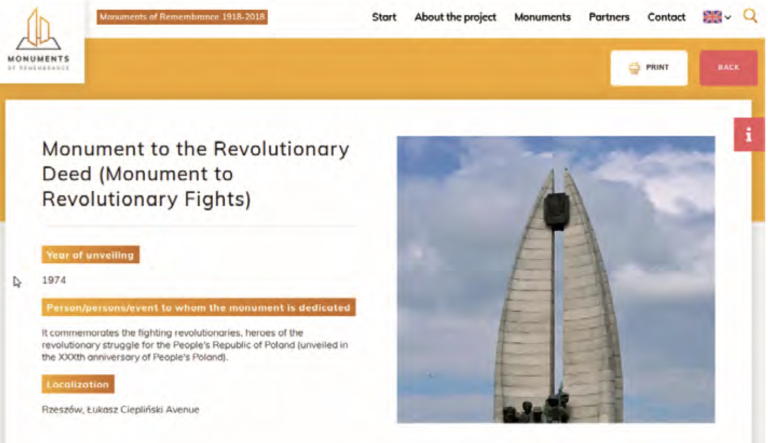

Despite the Decommunization Act, today many traces of the communist times can still be found all over the country, such as the Monument to the Revolutionary Deed which towers over the city of Rzeszów in South-East Poland. It is almost 40 metres high and includes the figures of a peasant, soldier, and worker with the banner of the revolution. Due to its communist connotations, it should no longer be there after March 2018. However, it is still standing, like other monuments in city centres. In Rzeszów, the city authorities want the monument to be preserved and are trying to include it in the register of historic monuments. In turn, in the case of the Rzeszów Monument of Gratitude to the Red Army, the court overruled the opinion of the Institute of National Remembrance, and the mayor of the town stated that the monument is one of the most famous and recognizable buildings in Rzeszów and should remain “as a testimony to the history of the city.” It is not the only big city with a monument commemorating the past regime.

In Olsztyn, you can still see the monument to the Liberation of the Warmian- Masurian Land, commonly known as the gallows, and in the centre of Dąbrowa Górnicza there is a monument to the Heroes of the Red Banners, and at the Citadel in Poznań there is a 23-metre obelisk dedicated to the heroes of the Red Army. The monument in Olsztyn has been in the register of historical monuments since 1993. The Red Banners in Dąbrowa Górnicza will also be preserved, as local government and most of the inhabitants want to keep it as a “symbol of the city”.

Source: Alicja Pacewicz

Monument to the Revolutionary Deed, Project “Monuments of Remembrance 1918-2018”

See at: https://bit.ly/3pPlWRl

6. Debate on controversial historical figures and their monuments

For supporters, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, “operates on the premise that these present discrepancies are rooted in history, and the present and the past must, together, be critically engaged with.” However, a number of critics have begun to express concern at campaigns to ’whitewash’ history, with columnist Matthew D’Ancona arguing that: “There is a modernist urge to wipe away the past and replace it with the new, but we should resist it.” At its heart, the debate is about our relationship with history, and whether removing statues and monuments has a role to play in reappraising historic wrongs, or whether they encourage us to airbrush out difficult and contentious parts of our history, rather than engage with and understand them. Should monuments to controversial historical figures remain?12

Footnotes

- Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democraticculture

- Available at: https://debatingmatters.com/topic/monuments-to-historical-figures-shouldremain/

- Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfVHihyDH8w&list=PLfLx3lDPtE3Lpgbo4K0p- 4E5T3_e7U6yj&index=1 (approx. min 2:00 to 6:30)

- Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ik9J0Zb7Tnk&list=PLfLx3lDPtE3Lpgbo4K0p- 4E5T3_e7U6yj&index=4

- More information available at: http://www.muzeumprl-u.pl/index.php?id=55 (in Polish)

- Video available at: https://zachod.pl/559622/strzelce-pomniki-relikty-prl-u-rozebrane/ (in Polish)

- See at: http://monuments-remembrance.eu/en/o-projekcie-3

- Jurašienė J. (2016): Ambivalentiškumo problema Grūto parke. Atvejo studija (baigiamasis magistro darbas), [‘The problem of ambivalence in Grūtas Park. Case study (master’s thesis)’],Vilniaus Dailės akademija, p.37; Miles M. (2007): ‘Appropriating the ex-Cold War’. In: Art History & Criticism, no. 3, p.173. Available at: https://www.vdu.lt/cris/handle/20.500.12259/33635

- Debating Matters: Monuments to historical figures should remain. Available at: https:// debatingmatters.com/topic/monuments-to-historical-figures-should-remain/

- Institute of National Remembrance: ‘Dekomunizacja pomników’ [‘Decimmunization of monuments’]. Available at: https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/upamietnianie/dekomunizacja/dekomunizacjapomnikow/ 45390,Komunikat-w-sprawie-usuwania-z-przestrzeni-publicznej-pomnikowpropagujacych- kom.html

- Histomag (2017): ‘Goń z pomnika… wszystkich naraz. Jak świat opanowała wojna na pomniki’ [‘Chase the monument … all at once. How the world was taken over by the war on monuments’]. Available at: https://histmag.org/Gon-z-pomnika…-wszystkich-naraz.-Jak-swiatopanowala- wojna-na-pomniki-15730

- Debating Matters: Monuments to historical figures should remain. Available at: https://debatingmatters.com/topic/monuments-to-historical-figures-should-remain/