CROATIA:

What is (Economic) Transition? – Economic Transition from The 1980s Onwards

Authors: Vedran Ristić, Vedrana Pribičević & Caroline Hornstein Tomić

I. Overview

This lesson focuses on tourism as a case study to teach students about the transition from a command to a free market economy. To analyse the effects of tourism on the economy and everyday life, it compares tourists’ experiences from before and after the transition period.

II. Students’ age

This lesson is aimed at 4th grade grammar school students aged 17-18.

III. Objectives

Learning outcomes based on the national curricula: POV SŠ B.4.1. Students examine different forms and stages of economic development in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in Croatia, Europe, and the World.

Lesson outcomes:

- The students will be able to:

- Define the concept of economic transition.

- Analyse the effects of economic transition on Croatian tourism.

- Evaluate the pros and cons of command and free market economies.

Lesson aim:

- To inspire reflection on processes of economic transition and raise awareness about positive and negative outcomes attached to this notion.

IV. Key concepts

Worker self-management, command economy, free market economy, transition (privatization, liberalization, transformation, reconstruction, convergence, war economy).

V. Key question

How did the economic transition affect Croatian tourism and how did it affect the everyday lives of the Croatian population?

VI. Prior knowledge

Based on the curriculum, students should be familiar with most of the following topics relevant for understanding the economic transition: The Great Economic Crisis of 1929, the economy of the USSR, the rise and fall of communism, the Cold War, globalization, European integration, and the Croatian War of Independence (Homeland War)

VII. Step-by-step description of the lesson

ACTIVITY 1: What did you do last summer? (2 min)

The teacher asks students where they went for vacation last summer (or the summer before that considering the COVID-19 situation) and leads a short introductory conversation about the topic.

ACTIVITY 2: Head in the clouds (5 min)

The teacher asks students the following question: Do you know what constitutes a command economy? Students write down at least three terms which they associate with a command economy. A live word cloud can be created via www. mentimeter.com or similar tools, or the answers can be written on the board. The teacher and students read and comment on the answers. The same procedure is repeated for the question: Do you know what constitutes a free market economy?

ACTIVITY 3: Rewind the tape (5 min)

The teacher asks several questions (see APPENDIX – SOURCE A) about the economic history of Croatia – with a special focus on the 1980s, when Croatia was a republic in the Yugoslav Federation – either through an interactive quiz, using an online tool, or PowerPoint. Students answer the questions based on prior knowledge, deduction or speculation based on what knowledge they might already have on this subject. The teacher encourages students to give answers which they may have picked up from their parents, relatives, friends, school, or immediate environment, even if they are not sure of their accuracy. The questions in the test are designed to challenge misconceptions and prejudice, both in those who idealise and those who denigrate Croatia as part of socialist Yugoslavia. Once all the students have given their answers, the teacher presents the correct answers on the next slide with an explanation, facts, charts, figures, and discusses these answers with the students.

ACTIVITY 4: Introducing workers’ self-management (7 min)

The teacher gives the students a card containing information on workers’ self-management in Yugoslavia (see APPENDIX – SOURCE B). After reading the students answer the questions provided.

ACTIVITY 5: Soaking up some sun (7 min)

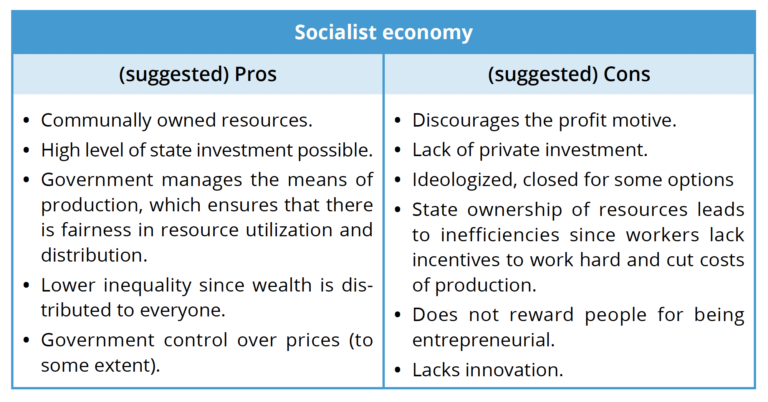

Students read the text “Tourism – the socialist way” (see APPENDIX – SOURCE C). The goal is to present Yugoslav socialism through the lens of tourism, which might prove useful in several ways. Firstly, students can draw on their personal experience of travelling for leisure, so they can easily relate and compare historical accounts with tourism today. Secondly, tourism is an important sector of the Croatian economy, both historically and currently; it can effectively be used to illustrate institutions of socialism, the transformation/transition period and nascent capitalism. Upon reading the text, students are asked what the main pros and cons of command economy tourism might be. A table is either projected or drawn on a flipchart/board.

ACTIVITY 6: A tourist trap (20 min)

The Teacher divides the students into 5 groups. Each group reads the citations of tourists from the table “Let’s go on a summer vacation!” (see APPENDIX – SOURCE D) and one of the 1A-1E texts (see APPENDIX – SOURCE E). The goal is to study the citations and determine which people would travel to which destination and identify reasons for this choice. After the task is completed, the spokesperson of each group presents their solutions. The teacher encourages comments and helps students amend the table containing the pros and cons of command economy tourism.

ACTIVITY 7: Winds of war and economic transition (7 min)

The teacher gives students a card containing a text about the Homeland War and its effects on tourism in Croatia (see APPENDIX – SOURCE F). After reading this information, students answer the questions provided.

ACTIVITY 8: Head in the sand

The teacher presents several questions (see APPENDIX – SOURCE G) on the transition process, either through an interactive quiz, using www.mentimeter. com, or a PowerPoint presentation. Students answer the questions using any prior knowledge they might have on the subject. The teacher encourages students to give answers which they may have picked up from their parents, relatives, friends, school, or immediate environment, even if they are not sure of their accuracy. Once all the students give their answers, the teacher presents the correct answers on the next slide with an explanation, facts, charts, and figures and discusses them with the students.

ACTIVITY 9: I Know What You Did Last Summer (20 min)

The teacher once more divides students into 5 groups. Each group reads texts 2A-2E (see APPENDIX – SOURCE H) and again uses quotes from the tourists in the table “Let’s go on a summer vacation!” (see APPENDIX – SOURCE D). The goal is to study the citations and determine which people would travel to each destination following the transition. After the task is completed, the spokesperson of each group presents their solutions. The teacher encourages comments and helps students understand how vacation plans might have changed for each person as the structure of the economy changed due to the transition process.

ACTIVITY 10: Discussion and assessment (10 min)

The teacher asks a series of questions intended to encourage discussion about the transition period (See APPENDIX – SOURCE I). The teacher can choose which questions to ask depending on the emphasis she/he wants to make.

APPENDIX

SOURCE A: Myth busting

� Q1: In Yugoslavia, everyone had a job – there was no unemployment.

FALSE

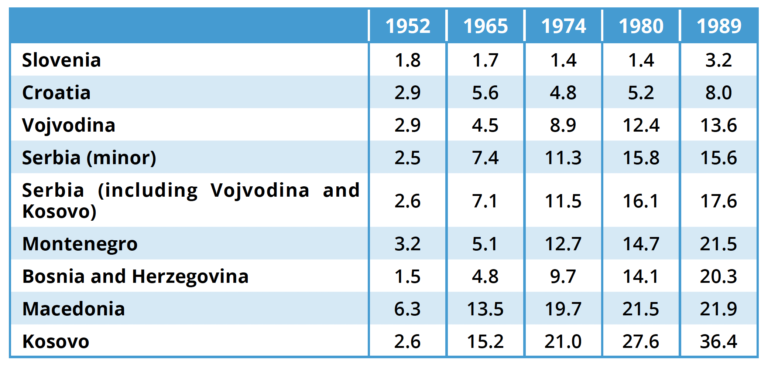

Unemployment rates in Yugoslavia (source: OECD)

Source: The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies1

Explanation: Yugoslavia started having problems with unemployment as early as the mid-1960s. The average unemployment rate increased from 6% in 1965 to over 16% in 1990, though there were substantial differences across the republics: Slovenia had practically full employment, while Macedonia and Kosovo had particularly high rates of unemployment.

� Q2: Yugoslavia/Croatia was an export giant.

FALSE

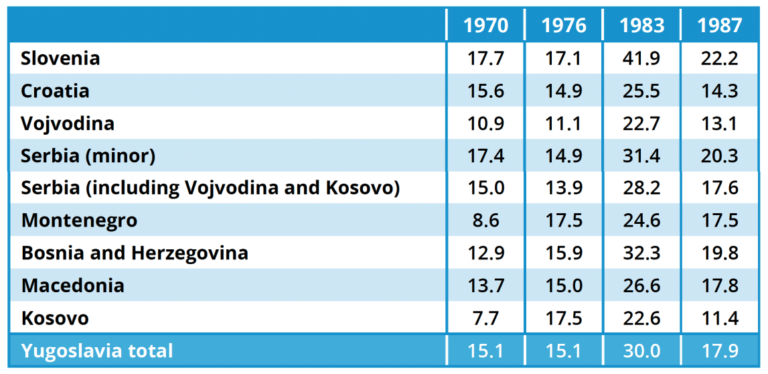

Exports as percentage of GDP (Source: OECD)

Source: The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies2

Explanation: The domestic market was much more important than the foreign market, with 82.1% of production allocated to a domestic or regional market. This characteristic of the economy persists even after the break-up of the country, albeit not in Slovenia, but things begin to change under the influence of the crisis of the eighties.

� Q3: Standards of living simply continued to increase in Yugoslavia.

FALSE

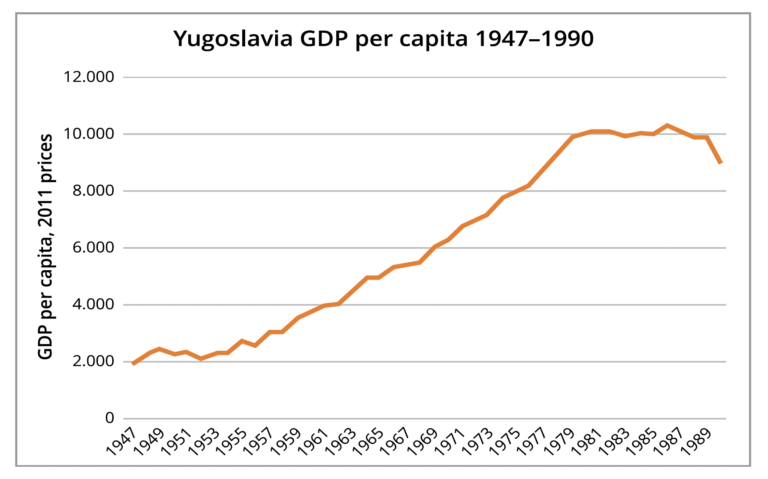

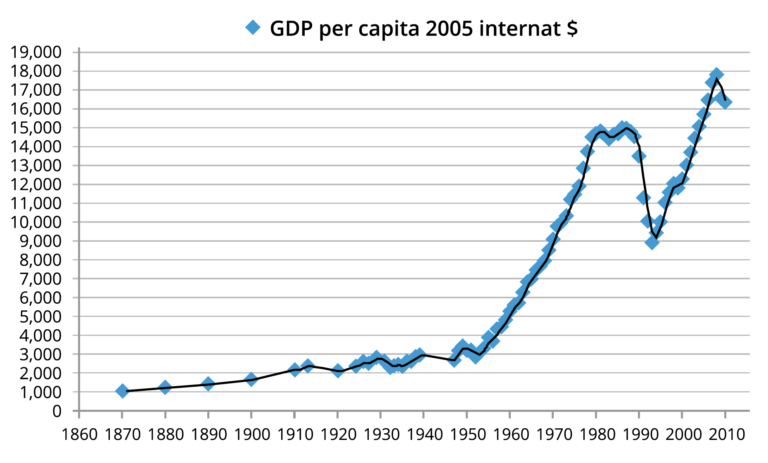

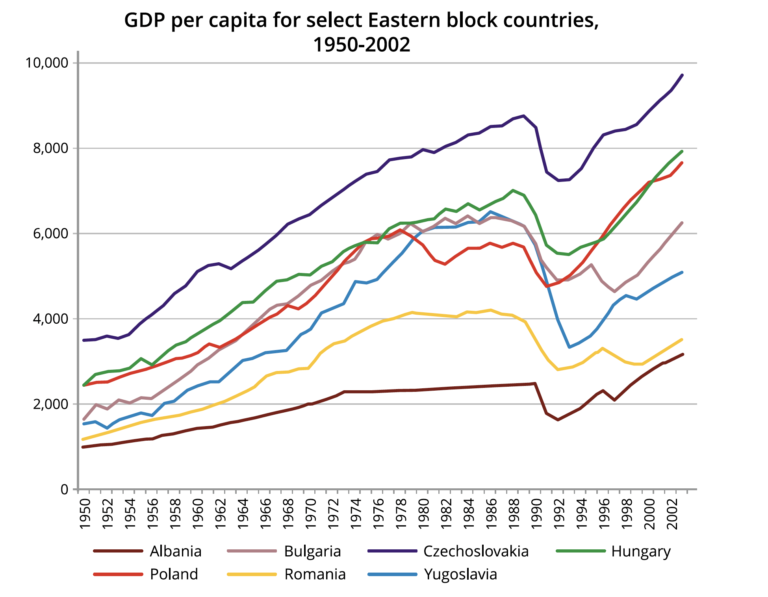

GDP per capita (Source: Maddison database)

Source: Maddison database3

Explanation: While GDP per capita increased by a factor of five from 1947 to 1979, the 1980s were marked by stagnation or even a fall in GDP per capita from 1988 to 1990.

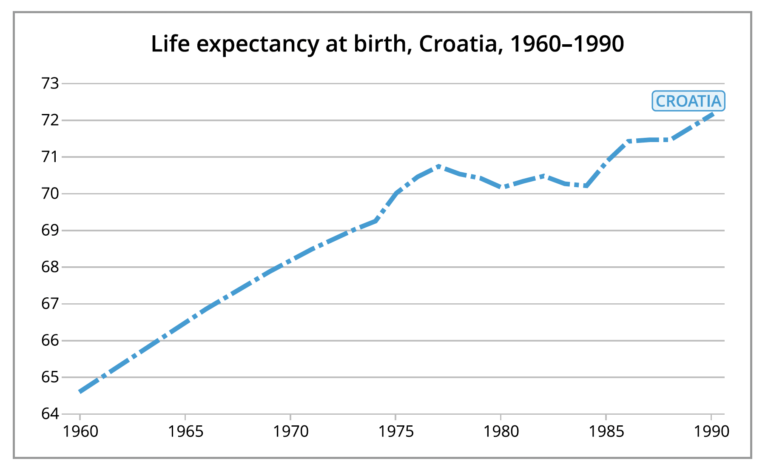

� Q4: Life expectancy increased during the period when Croatia was part of Yugoslavia.

TRUE

Life expectancy at birth (Source: World Bank)

Source: World Development Indicators4

Explanation: Over the course of thirty years, life expectancy at birth in Croatia increased by 7,5 years.

SOURCE B: Workers’ self-management

The Yugoslav model of socialism was conceived after the political split between Yugoslavia and the USSR in 1948. Prior to the Stalin-Tito schism, Yugoslavia had all the ingredients of a socialist economic system: party control of the economy, central planning, and state ownership of the means of production brought about through nationalisation and the expropriation of private property, a state monopoly over the most important spheres of the economy (investment, banking, foreign trade) and administrative control of most prices. The central ized system of economic administration lacked proper incentives for workers and firms, so it became necessary to introduce some elements of a market to stimulate growth. The new economic model introduced in 1950 was assigned the direct management of public property to the workforce of enterprises, introducing the principle of self-management into the economy. The factories, however, would not be owned by workers (nor by the state, for that matter), but only managed by them. The workers could appoint directors, but only the ones who had the support of the Communist Party. With further reforms in the 1970s, a special blend of economic models emerged with features of all three groups – socialist, market and self-managed – that were further sustained by the country’s favourable international relations. The openness Yugoslavia enjoyed throughout the 1960s and 1970s was a prerequisite for the development of tourism, where substantial government investments were directed towards constructing large hotel complexes aimed at increasing the capacity to accommodate domestic and foreign guests.

- Can you define workers’ self-management in one or two sentences?

- Which three key concepts would you highlight in defining workers’ self-management?

- Would you relate workers’ self-management more closely with a planned economy or free market economy?

- Are there any ambiguities you can identify in the concept of workers’ self-management?

SOURCE C: Tourism – the socialist way

Tourism was an extremely important sector of the Yugoslav economy, with Croatia contributing about 80% of the total number of tourists in the entire federation. Tourism was also an important source of foreign currency which was often used to offset negative trade balance trends emerging in the 1980s. In other words, revenue from tourism often paid for the difference in value between exports and imports, allowing Yugoslavia to run a sizable trade deficit.

The vision of a satisfied and thus productive worker was a key cornerstone of socialist ideology, so companies invested great efforts to provide or subsidize vacations for workers. Just after World War II, a two-week paid leave was introduced; by 1973, Yugoslav workers had 18-30 days of paid leave a year. Government also subsidized transportation to vacation destinations. From 1965, the government and firms paid a holiday allowance to workers which amounted to about 1/3 of an average salary. Companies often had their own seaside resorts which their workforce could use for vacation at an affordable price.

SOURCE D: Let’s go on a summer vacation!

Select quotes from magazine polls in the 1980s

In my 22 years of employment, I’ve rarely missed the opportunity to go on summer vacation. I mostly stayed in our union resort because it is the cheapest. This year I’ve planned a vacation to Zadar myself. I plan to spend around 2000 dinars with my wife and daughter.

– Milan Medaković, storehouse worker.

I spend my summer vacation at my mother in law’s house on [the island of] Pašman. […] My child is down there for the entire summer, and I have a greater degree of comfort there than anywhere else.

– Velimir Margetić, director in a state company.

This year I plan to stay with my family in a resort in Makarska for fifteen days. There will be days of sunbathing, swimming, indulging in some fine drinks and leaving behind everyday worries. I will set aside 2500 dinars out of our house budget for the summer vacation.

– Tomo Šuica, storehouse worker in an agricultural company from Karlovac.

I can only speak for myself because I work in a factory and in agriculture. I work in agriculture because our income in the textile industry isn’t high enough to cover living expenses. I can’t, for instance, leave my hay at home and go to the theatre for pleasure, or somewhere else the young might go.

– Branko Crnek, a textile worker from Krapina.

I’ll spend my vacation home on the lawn mower with a pitchfork in my hands. I’ve never spent it outside my place of residence. Given the opportunity, I would spend it in our resort, where most Gavrilović workers go. I’m not going because I haven’t managed to save any money.

– Dragan Dobrić, a meat industry worker from Poljana near Topusko.

I can’t go on vacation because my income is too low, around 1800 dinars, which I use to support five children. I have three acres of land I must work to grow the bare minimum for my family. I would love to go to the seaside, but it’s not possible for me.

– Branko Šiljac from Hrašća near Ozalj.

The offer of “tourist merchandise” is limited because it’s not primarily a consumer society, and what we’ve seen is no poorer than what we’ve seen in much larger quantities in all tourist destinations around the world. The buyers should look for what Yugoslavia is most known for – crystal, embroidery, woodcarvings. […] These independent, brave people aren’t used to putting up with spoiled “ugly Americans”! Be “European” – reserved, polite, and unobtrusively dressed.

– Charlette L. Grable, American tourist.

SOURCE E: Destinations

1A Worker’s resorts

Companies could direct a part of their resources into the development of tourist infrastructure to secure affordable, or even free vacations in their own resorts. The accommodation and service would be rudimentary, following the “bed, plate and sun” principle. In some areas local tourist businesses saw the resorts as competition, while in others they were the spearhead of tourism. In the off-season some hoteliers made arrangements with work organizations to fill their capacities by lowering prices. As the workers’ living standard rose, so did their expectations, therefore some upgraded their resorts into B category hotels. There were 80,335 beds in worker´s resorts in Croatia in 1988, which made for 24% of all domestic stays. Union councils and companies with no resorts of their own made arrangements with private accommodation holders. So, in the early 1980s, a good part of the Makarska riviera was under that kind of lease. Unions could also secure no-interest loans which could be paid over several months. Sometimes, the poorest workers would be sent on vacation for free.

- How did the communal ownership system enable workers to go on vacation?

- What are the advantages and drawbacks of a “union” vacation as opposed to arranging one’s own vacation?

- Where is the “profit” in paying for workers’ vacation?

1B World trends

Although Yugoslavia tried to develop capacities which would attract elite tourism, the lack of a free market and an underdeveloped infrastructure significantly reduced offers which might be interesting to such guests. The locals saw tourism as easy seasonal income. One guest noticed: “the Yugoslav people are genuinely likable and hospitable […] but when they put on their waiters’ shirt, meaning when they are officially working, they give the impression of someone suffering forced labour.” One international poll on hospitality placed Yugoslavia 20th on a list of 23 countries. Still, openness towards foreign tourists brought in world trends that challenged the local conservative outlook. Well-off homosexuals that vacationed on the island of Rab were nicknamed the “consumer avantgarde”, and the 1970s saw the arrival of “hippies” at the seaside. In 1961, a naturist (nudist) camp, Koversada, was opened near Vrsar. The international naturist federation congress was held there in 1972. Spending outside of accommodation was low because of poor offers, with very few organized activities like diving, sailing etc. where tourist could spend their income, and the guests were mostly working class and hadn’t come on holiday to shop. The entertainment options on offer were also weak and mostly comprised small galleries and classical or pop music concerts. The Yugoslav part of the Adriatic was nicknamed “Europe’s most comfortable place to sleep”.

- What sorts of global trends entered Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s? Was this typical in communist states?

- Why do you think Yugoslavia scored low in the hospitality department?

- What prevented Yugoslavia from developing elite tourism capacities? Can that be linked to the command economy?

- Why do you think there were no major problems in the clash between conservative and modern worldviews?

1C Socialism and entrepreneurship?!

Although the construction of a private boarding house was financially risky, many increased their income that way. This sort of entrepreneurship was not in line with the socialist worldview, so state officials were not allowed to participate in this. The president of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia, Milka Planinc stated in 1972:

“Today people can get rich based on ownership with no work. […] What is this really about? Society has invested vast resources into roads, infrastructure, the construction of expensive objects that transformed the local landscape and made it commercially interesting. Society has invested billions, and the owner comes with his resources and builds a house there. Even if it costs 10-20 million, it is nothing compared to what society has invested and he exploits to his own advantage the entire process which took place over the last 10 years of our successful development.” The imbalance of foreign trade in the Socialist Republic of Croatia (SRH) had been precarious since 1966. The need for foreign currency made foreign guests desirable and “capitalistic” private entrepreneurship was tolerated.

- What was the official position of the government on private accommodation?What were the reasons behind the arguments? Would you agree with them? Explain.

- What does the foreign trade imbalance say about the Yugoslav economy?

- Why was entrepreneurship in private accommodation tolerated?

1D Hotel tourism

The 1960s and 1970s saw a construction boom in Yugoslavia for which the Adriatic was nicknamed “Europe’s construction site”. Hundreds of hotels, hotel complexes, camps and tourist settlements were built. Some of them are counted among high achievements of modernist architecture. They were intended for all guests, but the more luxurious hotels, like the hotel Adriatic in Umag, attracted almost exclusively foreign guests. In addition to luxury lodging, it offered a bar and terrace, casino, strip shows, and shows by world renowned artists like Tom Jones. The director commented: “We have no working hours. […] We’re here for the guests. We can sell our services only while the guests are here and are in a spending mood.” The hotel complex Haludovo on the island of Krk attracted foreign partners like the owner of the magazine Penthouse. Advertising in that magazine cost $15,000 per page, when at the same time, the price of a ‘’fićo“ (Fiat 500 car) was around $1,000. The tourist complex Babin Kuk near Dubrovnik offered everything needed for a longer stay including entertainment, sports fields, and shops.

- Why was there a construction boom in the 1960s and 1970s? For whom were the different properties built? Explain.

- Why did luxury hotels accommodate mostly foreign guests?

1E Feet in a washbowl

Despite all the state incentives and socialist ideas of equality, there were those who didn’t go on summer vacation at all. One poll in 1985 showed that 35% of those surveyed saw travelling for a summer vacation as a luxury. A washbowl was used to symbolize that mood in the 1970s, giving rise to a common refrain, “those who have money soak in the sea, and those who have none soak at home in a washbowl”. State allowances were used by many to supplement their income. If they were granted in the first half of the year, they would already be spent by the summer months. Farmers couldn’t leave on vacation because of summer field work. The residents of coastal areas left for hot springs or mountain areas, but more often stayed home to earn money by renting their rooms.

- What does the washbowl symbolize?

- Who couldn’t go on summer vacation, and why?

- Can the inability of some to go on summer vacation be seen as a failure of socialism? Explain.

SOURCE F: The Homeland War and the economic transition

The Homeland War and other conflicts in the territory of the former Yugoslavia were ruinous for the economy of the newly founded Republic of Croatia. Direct and indirect damages were estimated at $37 billion. GDP dropped by half, traffic was blocked for years, and a quarter of the territory was under occupation. From 1988 to 1992, tourism revenue fell by 87.3%. It was only after 1997, when the region stabilized and roads started to be renewed, that a slow recovery of tourism began.

Alongside the war, the economic transition to a free market economy was underway which included processes of privatization, liberalization, and stabilization. By 1996, the legislative framework for privatization was finished and about 2,500 companies valued at 25 billion DEM in total (about 50% of the value of the entire Croatian economy) changed their owners. In the process, a lot of political trading occurred, and companies were often passed to uninterested owners or those who made a quick profit by selling them on.

- How did the Homeland War affect tourism?

- What is economic transition to a free market economy?

- Reflect on how the period of the economic transition might have affected tourism.

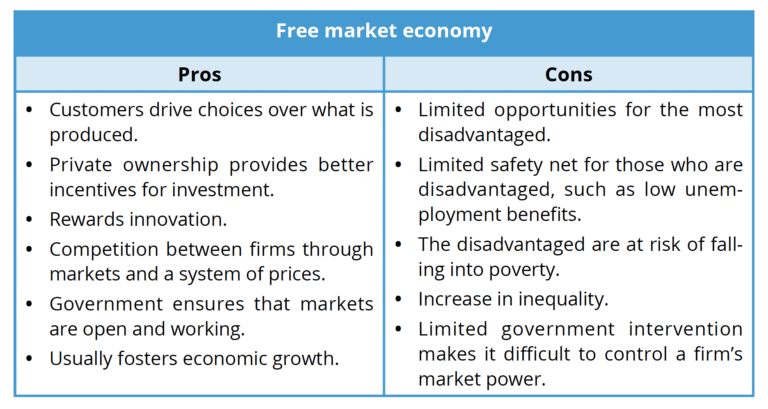

Upon reading the text, students are asked what they think the main pros and cons of a free market economy are. This table is either projected or drawn on a flipchart/board.

SOURCE G

� Q1: The Croatian economy was greatly set back by the Homeland War.

TRUE

Source: Maddison database5

Explanation: During the Homeland War, in the period between 1991-1995, GDP per capita had fallen to the levels of the early 1970s, which is a twenty-year setback. It was only in 2004 that GDP per capita returned to the highest levels of the 1980s.

� Q2: The economic setback produced by the Homeland War was exclusively to blame for the fall in GDP per capita.

FALSE

Source: Maddison database6

Explanation: During the Homeland War, in the period between 1991-1995, GDP per capita had fallen to the levels of the early 1970s, which is a twenty-year setback. It was only in 2004 that GDP per capita returned to the highest levels of the 1980s.

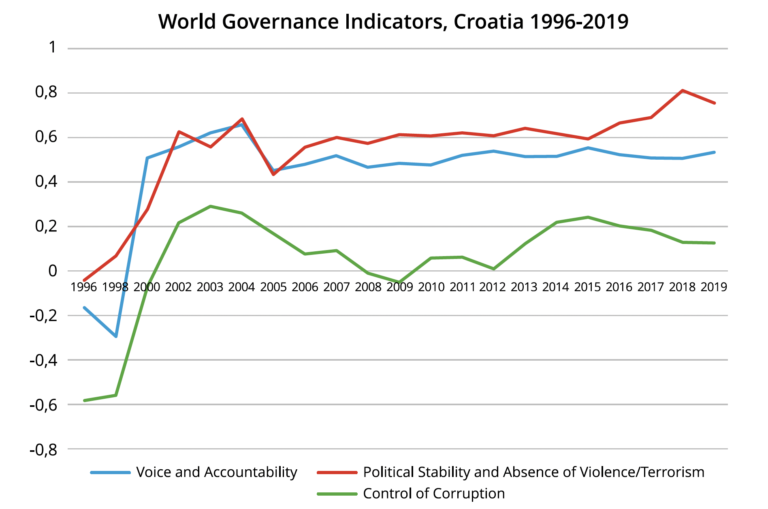

� Q3: The transition period in Croatia also lead to noticeable democratization.

PARTIALLY TRUE

Source: World Bank WGI7

Explanation: Complex measurements of the democratization of society are included in the World Bank’s Governance Indicators which are a composite of many different indexes. “Voice and Accountability” captures perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. “Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism” measures perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism. “Control of Corruption” captures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. In the second half of the 1990s and at the beginning of the 2000s, indicators improved, only to level off in the period from 2004-2019, which means Croatia’s democracy was slow to consolidate. Some improvements in the political stability indicator coincide with accession to EU, while indicators showing control of corruption worsen in the same period.

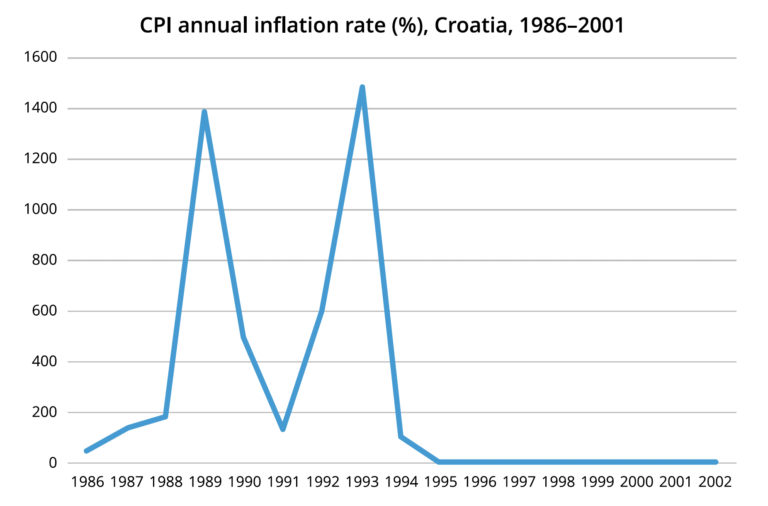

� Q4: Croatia has a history of high inflation, especially during the early period of the transition process.

TRUE

Explanation: Croatia had endemically high inflation in the years before the breakup of Yugoslavia. It entered the transition period with an inflation rate of 1400% per year in 1989. There was a second spike in inflation during wartime in 1993, where it reached 1500% per year. The stabilization programme which aimed to cut inflation successfully reduced the inflation rate to below 4% in 1995. The programme included the introduction of a new currency – the Croatian kuna – and it assured its full convertibility to other currencies.

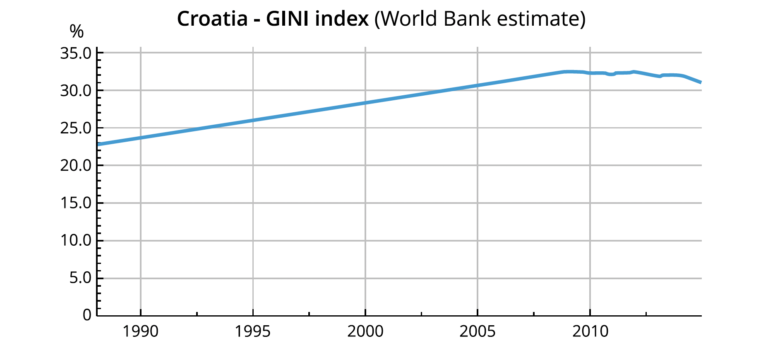

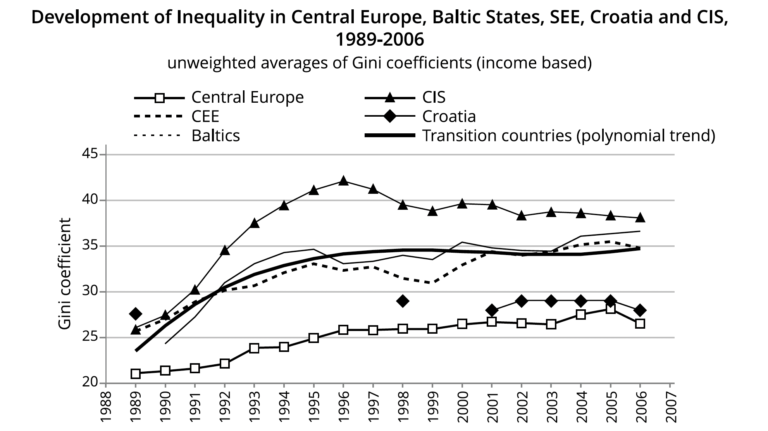

� Q5: Economic inequality increased greatly during the transition period.

FALSE

Source: The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies10

Explanation: The Gini coefficient, which measures inequality in the distribution of income, increased from 22.8 in 1988, to 32.6 in 2009. Since no data exists for the period from 1989 to 2009, some estimates suggest that Croatia has had a remarkably stable Gini coefficient during the transition period, unlike the Commonwealth of Independent States (including Russia), which had a considerable rise in inequality. Since then, only minor changes have occurred, leaving Croatia with a level of income inequality only slightly above that of the Central European transition countries on average.

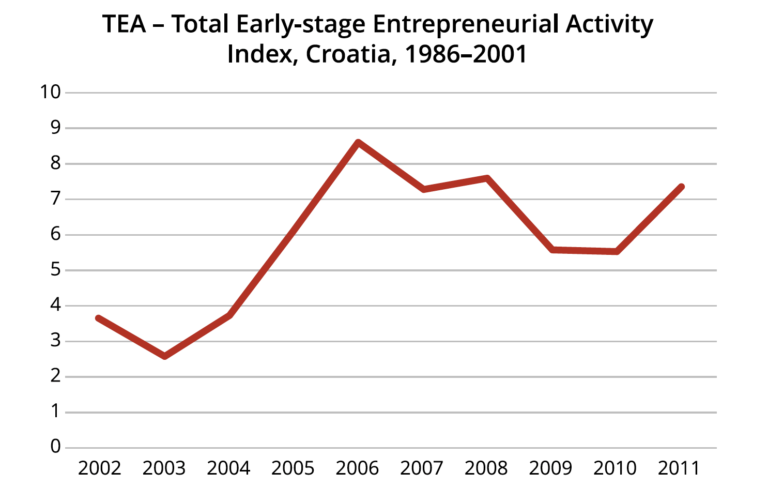

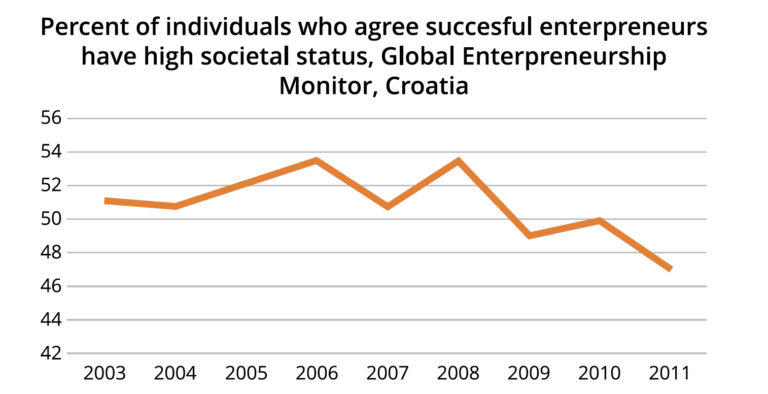

� Q6: During the transition period, entrepreneurs in Croatia did not have a positive public image.

TRUE

Source:Global Entrepreneurship Monitor12

Explanation: While the number of entrepreneurs increased according to the TEA index calculated by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, this was not followed by improvements in the public image of entrepreneurs. At the advent of recession in 2009, less than 50% of respondents agreed that successful entrepreneurs held high social status. Privatization had tarnished the image of entrepreneurs. This is also visible in the way in which they were portrayed by the media: in 2011, only 40.9% of individuals agreed that entrepreneurship received sufficient media attention. Notwithstanding the negative public outlook on entrepreneurial activity, 65.33% of respondents agreed that entrepreneurship is a desirable career path.

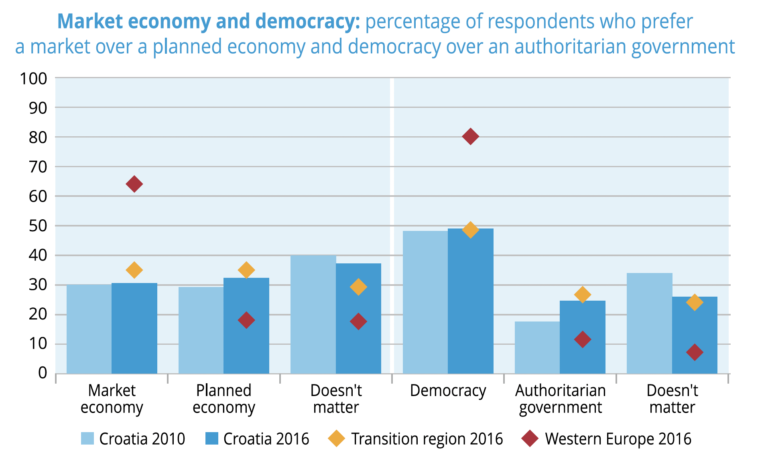

� Q7: Individuals in Croatia hold mostly negative views on the market economy.

TRUE

Source: EBRD. Life in Transition III13

Explanation: The latest Life in Transition report by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has shown that Croatian support for a market economy is among the lowest in the transition region, with only 31% of respondents unequivocally supporting the system as opposed to any other alternative. Attitudes towards democracy are more positive, with 49% preferring it to any other type of political system. Overall, more than one-third, and around a quarter, of respondents expressed indifference to the type of economic or political system which exists in Croatia, respectively.

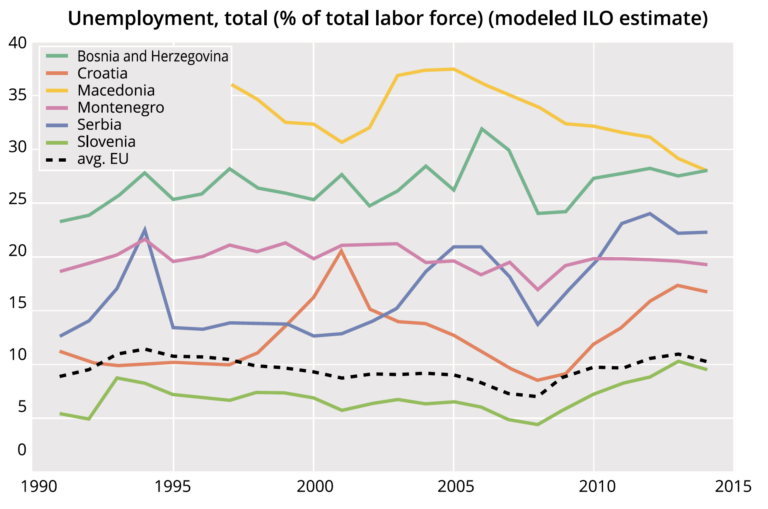

� Q8: During the transition period, the rate of unemployment in Croatia increased significantly.

TRUE

Source: Gapminder14

Explanation: At the beginning of the transition, unemployment in Croatia was more or less in line with the average in the EU. In the early 2000s, it had nearly doubled, almost approaching levels of unemployment seen in Montenegro. More remote parts of Yugoslavia had already recorded high unemployment rates at the beginning of the transition period, signifying large, persistent disparities between the Yugoslav republics. The rise in unemployment in Croatia in the decade following the war could be attributed to economic transformation and the deindustrialization. The unemployment rate decreased during a period of economic expansion before the financial crisis of 2008 and again after Croatia’s accession to the EU, amongst other factors as a result of increased emigration.

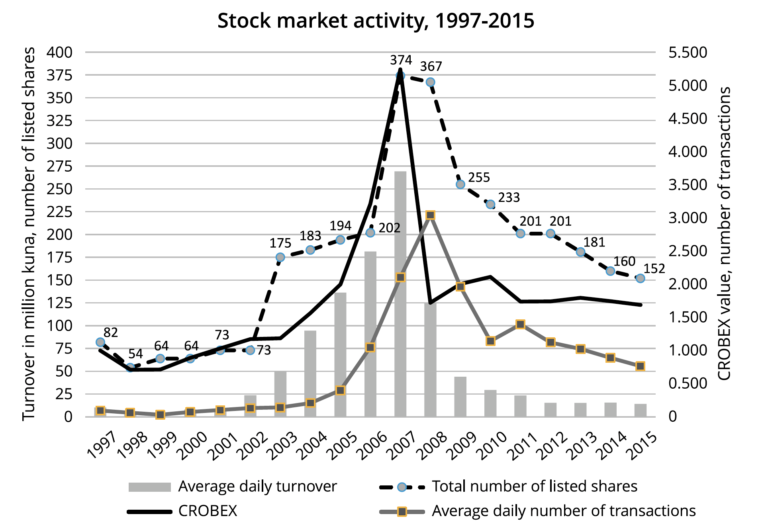

� Q9: The transition period in Croatia was marked by the emergence of capital markets.

TRUE

Source: 20 years of the Croatian Capital Market – adapted from Zagreb stock exchange reports15

Explanation: The Zagreb stock exchange held a dominant role in the Western Balkan region until 2008, when its market capitalization significantly decreased due to the global financial crisis and the economic downturn. The expansion of the stock market can be attributed to several liberalization reforms conducted in the 1990s, ranging from opening the stock market to foreign investors to establishing dedicated financial regulatory institutions.

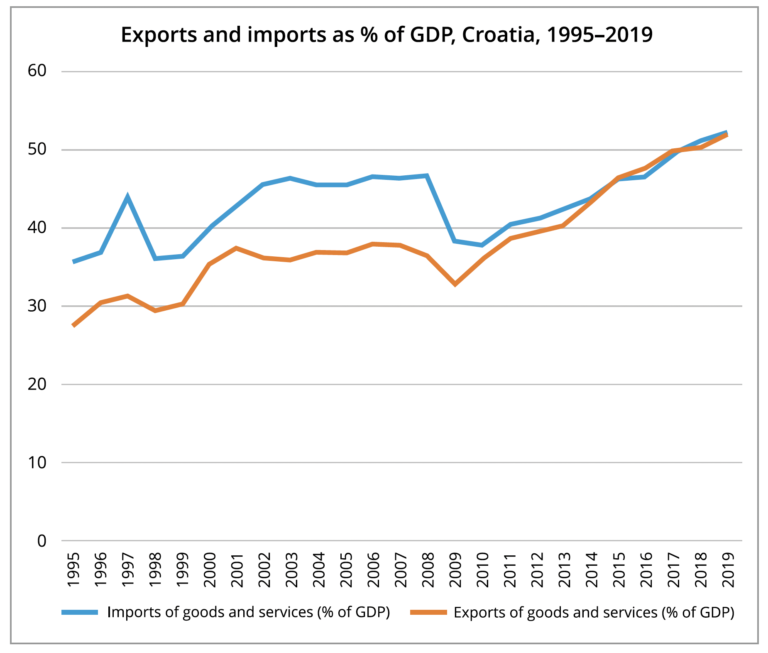

� Q10: During the transition period, imports to Croatia increased while exports decreased.

FALSE

Source: World Development Indicators16

Explanation: During the transition period, Croatia´s economy became significantly more internationalized, with exports rising from 27% of GDP in 1995, to 52% of GDP in 2019. There were two catalysts in this process: the crisis of 2008 and Croatia’s accession to the EU. The difference between exports and imports had been virtually eliminated since 2010, with exports and imports more or less moving in unison.

SOURCE H: Destinations revisited

2A Worker’s resorts

The worker’s resort Reflektor, on the island of Murter, was built in 1968. It is owned by the labour union of train drivers, so ownership did not change during the transition period. The main goal of a worker’s resort is to ensure workers can take vacations where “profit is not the prime objective, but workers and pensioners are able to enjoy a vacation at an elite destination in the Adriatic (with full board) at very affordable prices.”

Dalibor Petrović, a train-driver from Bjelovar, deputy director of the train driver’s union and director of the worker’s resort:

‘’As companies were privatized, worker’s resorts were either sold or turned into commercial enterprises. A well-known worker’s resort – far better than the one we have at Slanica – belonging to Podravka in the city of Pirovac was dismantled, together with a number of others. The train driver labour union took over the ownership of the Reflektor resort in 1993, which required substantial material and human resources – but we are proud of what we’ve accomplished today. We are the only worker’s resort in the entirety of the Adriatic where a worker or pensioner, and the members of their family, can take a summer vacation at an attractive tourist location. The accommodation is only 5 metres from the sea and, together with full board, costs around 165 kuna per day. We are lucky that train drivers acquired such a property back in 1968 and were able to preserve it.”

- What changed after the transition?

- How did Reflektor manage to maintain itself?

- Why do you think private companies don’t invest in worker’s resorts like their socialist predecessors did?

- How do private companies today care for workers?

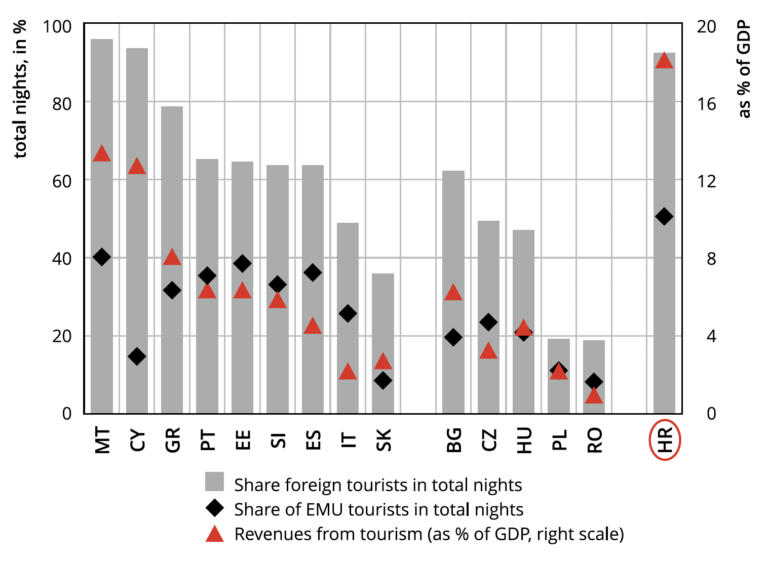

2B World trends

Tourism is one of the most important sectors in the Croatian economy. The economic structure is marked by a lack of diversification, most visible in the excessive dependence on the tourism sector. In terms of the relative size of tourism revenues (percentage of GDP), Croatia stands out among traditional tourist countries of the Mediterranean such as Greece or Spain, but also has a higher share of tourism than the island economies of Malta and Cyprus. Globally, Croatia’s share of tourism in GDP is only surpassed by so-called island micro-economies such as the Maldives or the Seychelles, which has profound effects on the economy.

Tourism from the eurozone is a major source of revenue for Croatia, with over 50% of guests originating from the common currency area, bringing in about 70% of the total revenue in tourism.17 Traditionally, the most common guests from that group are those from Italy, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia. This graph illustrates Croatia’s eurozone tourist structure vis-a-vis some selected countries of Europe and main tourist competitors within the eurozone. A considerable number of tourists also come from the United States, with Dubrovnik as main attraction because it has been featured in shows such as Game of Thrones and Star Wars. Another niche emerged in the post-transition period, elite tourism, where property development was mostly stifled by unresolved property rights. In other words, it was extremely difficult to find large plots of land for property development which had undisputed ownership. A large plot of land with a single owner is needed to develop luxury resorts.

Source: Croatian National Bank

- What changed after the transition?

- Who profited most after the transition?

- What problems does an economy, which is excessively dependent on tourism face?

- Is a “tourism dependent economy” sustainable?

2C Free entrepreneurship or free rentierism?

Croatia has some 100,000 registered private renters who rent out their properties, mostly for short-term rentals to tourists. Owners of these properties pay the lowest taxes of all income earning individuals: a lump sum tax of 300 kuna per bed per year. The increase in tourism in the aftermath of the transition had a profound effect on property prices. For instance, in the period from 1990 to 2010, the prices of newly built properties increased by 92%. These prices rose further when Croatia entered the EU. Digital platforms increased the supply of tourist accommodation, leading to the airbnb-ization of city centres along the coast. However, digital platforms also suggest prices to those who rent out their properties, which increases competition and lowers the prices of accommodation for consumers.

- What changed after the transition?

- Was renting more profitable for private individuals before or after the transition? Explain.

- How do you think the collapse of the command economy and the social support system has affected the rise of private renting?

2D Hotel tourism revisited

The Haludovo Palace Hotel on the island of Krk was designed in 1971 by Boris Magaš, a renowned Croatian architect and member of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The project was funded by Bob Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine, who opened a casino on the property which quickly went bankrupt. The hotel was owned by the Brodokomerc company and served as a shelter for refugees during the war. The hotel was bought by its director, who received loans from the Croatian Bank for Reconstruction and Development to prepare the property for the tourist season, in 1995. However, he did not invest the funds in the property and an investigation was later opened. The court case lasted for more than a decade. The hotel had its last guests in 2001. Ultimately, the hotel was sold to a foreign investor who is unable to invest in the property due to a dispute over property rights and problems in the process of privatization. Today, despite being abandoned, it serves as a tourist attraction.

- What were the difficulties faced when the hotel was privatized?

- Should the Croatian government have done more to keep the hotel open or not? Why?

- How was the hotel able to function before the transition and what changed?

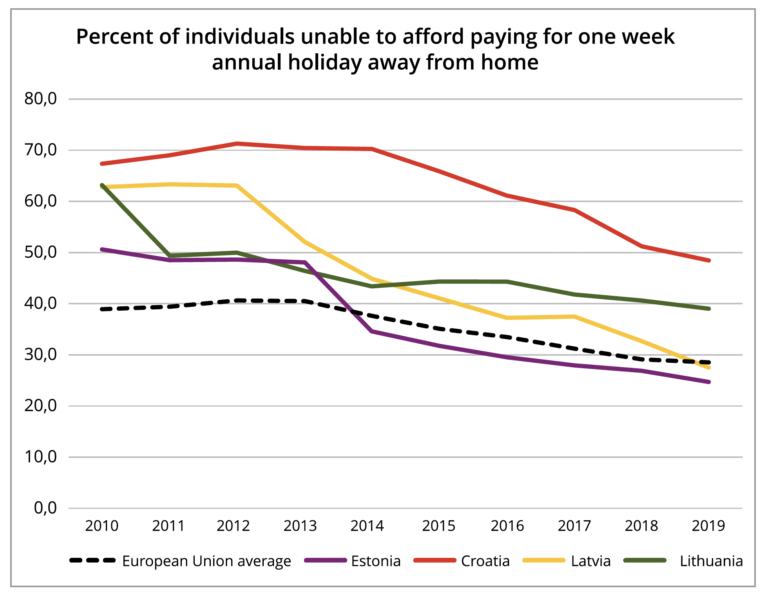

2E Feet (still) in a washbowl?

Source: Eurostat18

In 2019, nearly every second Croatian citizen older than 16 years of age was unable to afford a one-week annual holiday away from home. The EU average was 28.4%. Inside the EU, only the Romanians and Greeks fared worse, but the situation was even bleaker during the Great Recession of 2008, when approximately 70% of Croats could not afford paying for one week of annual holiday. In the same period, the champions of the transition, the so-called Baltic tigers, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania experienced a sharp decline in the percentage of individuals not being able to afford holidays, from 58.8% to 30.4% on average.

- When it comes to ordinary citizens and their vacations, are they better off or worse off after the transition?

- Reflect on the reasons why, in a comparison between EU-member states, the percentage of people who can afford a weekly annual holiday differs so greatly.

- To what extent is the ability to pay for a vacation an indicator of financial wellbeing?

SOURCE I: Questions for final discussion/essay

Was there a sound economic basis on which the socialist system could function? In the end, who paid for these vacations? Was this based on real productivity? Maintenance of the resorts was sustained by the companies and unions, how did they cover these costs? Did the state ultimately cover the costs, and by what measures (inflation, foreign debt, etc.)? Why don’t todays’ companies sustain worker’s resorts? Why is tourism today mostly run privately?

How do social concepts like justice, fairness, equality, transparency, loyalty, and equity, relate to the two economic systems in place before and after the transition? Which core values would you associate with the economy before and after the transition?

Are there “winners” and “losers” in the transition process? Are traces of the socialist economy still visible in your country?

Some theoreticians claim that the economic transition is ongoing. Using your knowledge of the situation in your country, discuss this question in class.

Footnotes

- The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. Available at: https://wiiw.ac.at

- Ibid.

- Groningen Growth and Development Centre: Maddison Project Database 2020. Available at: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database- 2020?lang=en

- World Bank, World Development Indicators. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/ source/world-development-indicators

- Groningen Growth and Development Centre: Maddison Project Database 2020. Available at: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database- 2020?lang=en

- Ibid

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators

- World Bank, World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worlddevelopment- indicators

- Gini index (World Bank estimate) – Croatia. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ SI.POV.GINI?locations=HR 70

- Leitner S. & Holzner, M. (2009): ‘Inequality in Croatia in Comparison. Research Report 355’, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, p.2. Available at: https://wiiw.ac.at/ inequality-in-croatia-in-comparison-dlp-1887.pdf

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Available at: https://www.gemconsortium.org

- Ibid

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2016): Life in Transition Report III, p.87. Available at: https://www.ebrd.com/publications/life-in-transition-iii.pdf

- Gapminder. Data documentation. Available at: https://www.gapminder.org/data/

- Grubišić Šeba, M. (2017): ‘20 Years of the Croatian Capital Market’. In: Zagreb International Review of Economics & Business, Vol. 20 No. SCI, 2017. Available at: https://www.hnb.hr/ documents/20182/2070697/s-026.pdf/e984ecbe-febc-4c69-a62c-b289908efc36

- World Bank, World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worlddevelopment- indicator

- Bukovšak, M.; Ćudina, A. & Pavić, N. (2017): ‘Adoption of the Euro in Croatia: Possible Effects on International Trade and Investments’. Croatian National Bank, p.10. Available at: https://www.hnb.hr/documents/20182/2070697/s-026.pdf/e984ecbe-febc-4c69-a62cb289908efc36

- Eurostat: ‘Inability to afford a one-week annual holiday’. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/