LITHUANIA:

The Transition Period in Lithuania: Social, Cultural, and Economic Challenges

Authors: Giedrė Tumosaitė, Tomas Vaitkūnas & Vaidotas Steponavičius

I. Overview

This lesson aims to help students identify problems related to the social, cultural, and economic aspects of the period of transition to democracy in Lithuania, critically using and analysing diverse information sources. The lesson is based on the new realities, experiences, and social roles that the transition period introduced, alongside the re-establishment of independence and democracy. It can also become the final summarizing lesson of the transition period.

II. Students’ age

2nd gymnasium grade (10th school year); the age of students – 16-17

III. Objectives

- Cognitive competence, which includes learning to learn, problem-solving, critical thinking, and a multi-perspective approach. Students would work with various sources of information during the lesson, identify problems, discuss them in groups, and encounter different opinions or points of view, thus strengthening their cognitive competencies.

- Creativity as a prerequisite for the capacity to raise questions independently. Searching for and identifying challenges, proposing a potential solution, and defending it in the group would develop students’ inner readiness to think critically and act “here “and “now “.

- Socio-emotional competence as a prerequisite to showing respect for people from different social and cultural groups, encouraging cooperation, and understanding the reasons for stereotypes. Working together, students would expand their collaboration skills.

- Subject competence. Students are expected to acquire the ability to link the political, economic, and social processes of the transition period; acquire knowledge that reflects the society of the 1990s.

IV. Key concepts

- The transition period – the transition from communism to democracy refers to a period when the state’s political, social, cultural, and economic system underwent a transformation in 1989/1991.

- Ethnic group – a community or population made up of people that share a common nationality, language, or ethnic origin.

- Migration – moving from one place of residence to another.

V. Prior knowledge

These lessons are the last in the series of 3-4 lessons about the transition period. Also, students must already have the following prior knowledge/have studied the following topics:

- Soviet policy before Gorbachev – the last years of stagnation, war in Afghanistan, economic downturn.

- The opportunity for change created by perestroika.

- The liberation of CEE countries from Soviet influence.

- The activities of the Helsinki Group, Kaunas Spring, Lithuanian Freedom League and the Catholic Church and their influence.

- The daily life of people before the transition.

- Establishing the Lithuanian Reform Movement in 1988.

- The re-establishment of the Lithuanian statehood in 1990.

VI. Description of the lesson

Objectives of the lesson:

Working in groups, and critically using historical sources, students will be able to:

- Identify issues related to the social, cultural, and economic aspects of the transition period.

- Discuss and reflect on social, economic or cultural aspects of the transition period from multiple perspectives.

- Justify the issues identified using diverse sources of information.

Duration of the lesson: 45 minutes

Materials and sources: whiteboard, 3 different handouts with information about the social, cultural, and economic aspects of the transition period in Lithuania (excerpts from various sources of information) (see annexes 1-3); flipchart paper/ computer and multimedia.

VII. Step-by-step description of the lesson

Introduction The teacher announces the theme/objective of the lesson, provides the criteria for the evaluation.

Summary information

The teacher provides summary information from the previous lessons about the most important political, social, economic, and cultural aspects of the period of transition to democracy and the changes in Lithuania and other CEE countries from 1989/1991 onwards, e.g., the restoration of the independence in Lithuania, transition from a command economy to the market economy, opening of the borders, etc.

ACTIVITY 1: Associations

The teacher provides a concept related to the phenomena of the transition period (less abstract concepts, e.g., Hopes and Fears in the 1990s, etc., can be used). Students are asked to brainstorm associations (i.e., simple associative descriptions) justifying the concepts in their own words. It is important that the associations are written down on the board/flipchart paper as they will be re-visited at the end of the lesson. After a short brainstorm, the teacher asks students to comment on why they chose these associations.

ACTIVITY 2: Identifying the social, cultural, and economic challenges/ concerns of the transition period

The task for students is to identify the most prominent social, cultural, and economic challenges/concerns of the transition period in Lithuania.

Step 1: each student receives one of the handouts (See APPENDIX – Handout 1-3, from p. 166–170). They are asked to read the handout and mark the transition period’s most critical challenges/concerns.

Step 2 (optional): students that have received the same handout form pairs and discuss the challenges/concerns that seem relevant to mention. The task is to select 2-3 significant challenges/concerns that can be brought to the later discussion.

Step 3: all students that have received the same handout join one group to present and discuss the issues they have selected and identify the most prominent challenge/concern (e.g., strengthening organized crime gangs, high rate of unemployment, emigration, unstable economy, etc.) on behalf of the whole group.

Step 4: the results of the group work are presented in the classroom. Each group has up to 2 minutes to present their issue and explain why that challenge/ concern is the most important. The teacher writes down the challenges on the whiteboard (flipchart, computer, etc.).

Step 5: the teacher provides a summary of the group work, emphasizing the main keywords, links, different approaches, and shares his/her observations.

ACTIVITY 3: Identifying the reasons

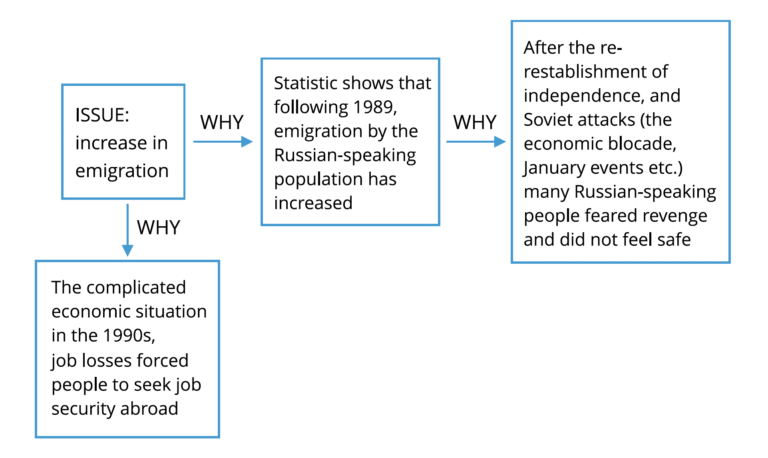

Students reflect on the social, cultural, or economic challenge/concern identified and provide a broader justification (reason) for it. Students work in the same groups (preferably not larger than 6 people), discussing issues, identifying the main statements/reasons, and then transferring them to the scheme or visual charter. A modified 5 WHYs method may be used, for example:

The role of the teacher in this task is to consult with and mentor students, leading students through these complicated situations.

The results of the group work are presented in the classroom. Each group has up to 2 minutes to explain their reasons. Other groups can comment.

ACTIVITY 4: Re-visiting associations

Having explored the transition period’s challenges and causes, the teacher asks students if they would like to modify their associations based on their new knowledge.

This exercise can be used as a part of the Evaluation.

Evaluation

Students are asked to write down on sticky notes (a whiteboard/flipchart paper and sticky notes, as well as online tools, e.g., Padlet, Mentimeter, etc., may be used) what they have learned during the lesson about a) the transition period; b) working together with classmates; c) oneself. After the sticky notes are placed on the paper(s), the teacher briefly summarizes learning outcomes and links them with the lesson objectives. Students can be asked to comment on whether and to what extent they have succeeded in achieving them.

VIII. Possible follow-up

Students who plan to study history on an advanced course in the following year are invited to consider a theme related to the transition period for their project work, e.g., memory research.

In cooperation with the language and literature teacher, the theme might be followed up with an essay of 300 words (e.g., the 1990s are different for everyone/ have we changed since the 1990s, etc.).

APPENDIX

Handout 1

A. My theory is this: in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was a powerful emotional boost associated with the Sąjūdis and rock marches. It was a euphoric period, full of idealism and the belief that things will suddenly be different in some miraculous way once we have independence. But it soon became clear that the formation of this “difference” would take time – firstly, a period of difficulty, chaos, and uncertainty would have to pass.

People don’t want to remember it. Therefore, another strong point in the narrative of Lithuania’s independence is the new millennium, which is related to positive things: accession to the European Union, NATO, stabilization of the new economy, real estate boom. In many ways, the 1990s was a traumatic experience: there is no need to remember processes that contrast too much with the vision of the Revival period because it was not expected.1

B. The economic downturn that began in the 1990s and the restoration of independence had an exceptionally negative impact on the position of men in society. During the Soviet era, the economy was dominated by industry for several decades, which absorbed a large amount of male labour, says Aušra Maslauskaitė, a sociologist and professor at Vytautas Magnus University (VMU).

“Men were strongly oriented towards workers’ positions. That was because working in such a job was often more rewarding than rubbing a university or institute bench because, in terms of pay, a worker’s salary was not much different from that of an engineer. […] For several decades, such a system continued, with many industries, hard work, hard-working men who contributed to the maintenance of the family “ – explains A. Maslauskaitė.

In other words, there were workers with much lower education among the men. In the 1990s, with the economic downturn, deindustrialization began, and many jobs were lost.2

C. Baltic way August 23, 1989

Photo by Vincas Tumosa (private)

Handout 2

A. In Lithuania in 1989, the application of the so-called zero acquisition of citizenship gave all permanent residents equal rights to acquire Lithuanian citizenship. The decision to obtain citizenship was taken by the majority of the country’s population. The Law on National Minorities adopted in 1989 stipulates that the Republic of Lithuania guarantees equal rights and freedoms to all its citizens, regardless of their nationality, and means respect for every nationality and language.

Industrialization of the agricultural sector and decentralization of the economy in 1980-1988 led to the acceleration of the migration of the Russian-speaking population to more remote areas of the Baltic States. That was a period of economic stagnation in the USSR. The establishment of the independent Baltic States in 1990 has led to the emigration of people of other nationalities (except Lithuanians) from the Baltic States. Russification has been replaced by strengthening the national identity – in some countries, it appeared to be more liberal, in others – less liberal. This was a time when the pursuit of economic autonomy, industrial reorientation and restructuring became very painful. Almost 60% of Russians worked in industry.3

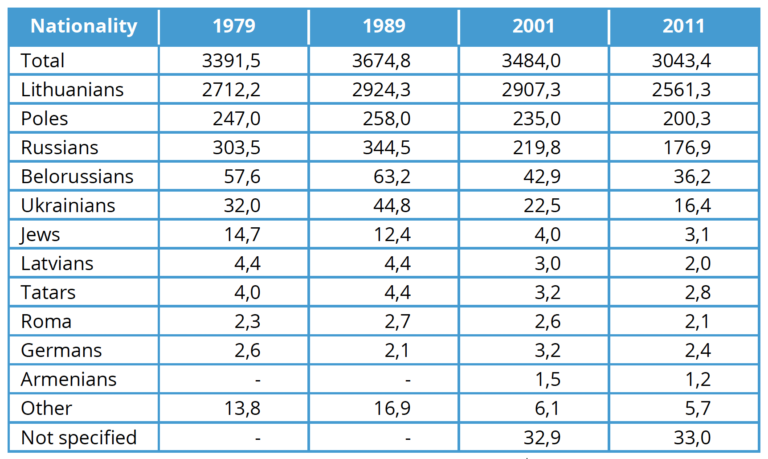

B. Composition of Lithuanian population by nationality (in thousands)

A. In Lithuania in 1989, the application of the so-called zero acquisition of citizenship gave all permanent residents equal rights to acquire Lithuanian citizenship. The decision to obtain citizenship was taken by the majority of the country’s population. The Law on National Minorities adopted in 1989 stipulates that the Republic of Lithuania guarantees equal rights and freedoms to all its citizens, regardless of their nationality, and means respect for every nationality and language.

Industrialization of the agricultural sector and decentralization of the economy in 1980-1988 led to the acceleration of the migration of the Russian-speaking population to more remote areas of the Baltic States. That was a period of economic stagnation in the USSR. The establishment of the independent Baltic States in 1990 has led to the emigration of people of other nationalities (except Lithuanians) from the Baltic States. Russification has been replaced by strengthening the national identity – in some countries, it appeared to be more liberal, in others – less liberal. This was a time when the pursuit of economic autonomy, industrial reorientation and restructuring became very painful. Almost 60% of Russians worked in industry.3

B. Composition of Lithuanian population by nationality (in thousands)

Source: Lithuanian Statistics, 2013

C. The restoration of Lithuania’s independence was met with fear and uncertainty by the most prominent national minorities living in the country and their communities. Pavel Lavrinec, Head of the Department of Russian Philology at Vilnius University, remembers the euphoria and hope for restoring statehood among Lithuanians 30 years ago, which contrasted with the rising tensions in the Russian minority.

“There were all sorts of fears: what will happen with the national language, Russian-language media and Russian schools. Many Russian speakers were sceptical about their future here in Lithuania, as were some Ukrainians, Belarusians and other people from Soviet republics. They did not have their own educational and cultural infrastructure here. But gradually, it became clear that nothing was terrible here. If you want to participate in Lithuania’s economic and cultural life, teach in Russian schools – pass the state language exam, and that’s it. Gradually, all fears dissipated “, – tells P. Lavrinec.

New Russian-speaking immigrants joined those who had lived in Lithuania for many generations: political and economic, who were dissatisfied with the situation in their home country. According to P. Lavrinec, unlike those who had lived in Lithuania for a long time, the latter were more motivated, studied the Lithuanian language more diligently, and were interested in the country’s culture and political system.4

Handout 3

A. In Lithuania, which regained its independence on March 11, 1990, the population still received an income and paid for goods and services in rubles until 1991, when temporary coupons were introduced. In 1990, the average salary was 283 rubles, and the average pension was 109 rubles. […] Today, we can find goods we never dreamed of or imagined at the time. 30 years ago, getting better quality meat was a problem, and coffee beans or bananas were a luxury item that you had to stand in the longest queue to get.

The goods of today and 30 years ago are light-years apart, but no less surprising is the price of some goods that are now taken for granted and are inseparable from our households. For example, the average cost of a colour TV set in 1990 was almost 740 rubles. That means that buying a TV at that time required more than 2.5 of the average monthly salary. A refrigerator, 30 years ago cost an average of 364 rubles or almost 1.5 salaries. Today, people can buy the cheapest TV set of incomparably higher quality for €200 or 23% of the average monthly salary. A new fridge can cost just over €200 or around 25% of the average monthly salary.5

B. At the grocery store

Photo by Z. Bulgakovas (private)

C. I think the Lithuanian people lived between hope and fear. There was still joy in regaining freedom and independence. Many people wanted to rejoin Western Europe as soon as possible and tried to contact foreign countries as much as possible. The difficult economic and social situation was also evident. What do I remember from that period? This was wild capitalism. Many people lost their jobs, and this put people under stress. I remember that the Baltic cities were littered with kiosks where people were desperately selling cheap things to survive. Others, meanwhile, made huge fortunes by exporting metals.6

D. Radical nationalists often argued that the transition of former communists and communist youth officials to private business was a part of an overall strategy to establish themselves in capitalism and the new states. Personal gain explains this well enough. However, this transition, of course, took place on a large scale and often in a corrupt form, often with the theft of state property. Both this and other forms of economic crime flourished, especially when Soviet laws had collapsed, and new free market rules had not yet emerged. […] The greatest threat to the future of the Baltic States was posed by the close ties of their new businessmen with organized crime, especially in the case of the embezzlement of state property. In Lithuania, in September 1992, the privatization of the four largest grocery stores in Šiauliai was stopped because local racketeers took control of it: auction participants and local officials were threatened. In similar cases, the property of the disobedient businessmen was set on fire or blown up. In the autumn of 1992, one bomb after another went off, especially in Latvia: it was the work of organized crime gangs fighting over property.7

Footnotes

- Vyšniauskas, K. (2014): ‘90-uosius Lietuvoje reikia sukurti. Pokalbis Su Jurijumi Dobriakovu‘. In: Literatūra ir menas. [The 90s in Lithuania need to be created. Interview with Yuri DOBRIAKOV’]. Available at: https://literaturairmenas.lt/publicistika/90-uosius-lietuvoje-reikiasukurti- pokalbis-su-jurijumi-dobriakovu (in Lithuanian)

- Platūkytė, D. (2020): ‘Dešimtojo dešimtmečio pokyčiai: vyrai laiką leido „ant sofutės gerdami alų, o moterys buvo stumiamos likti namie.”’ [‘Changes in the 1990s: men spent time “drinking beer on the couch” and women were pushed to stay home’] In: Lrt.lt, 27 Sept. 2020. Available at: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/1235314/desimtojo-desimtmeciopokyciai- vyrai-laika-leido-ant-sofutes-gerdami-alu-o-moterys-buvo-stumiamos-likti-namie (in Lithuanian)

- Kasatkina, N. & Leončikas, T. (2003): ‘Lietuvos etninių grupių adaptacija: kontekstas ir eiga’ [‘Adaptation of Lithuanian ethnic groups: context and course’], pp.9-45.

- Adomavičienė, L. (2020): ‘Rusas, BET gimtoji kalba – lietuvių: kaip per 30 metų pasikeitė tautinių mažumų padėtis Lietuvoje’ [‘Russian, BUT native language – Lithuanian: how the situation of national minorities in Lithuania has changed over the past 30 years’]. In: lrt.lt, 21 May 2020. Available at: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/1180376/rusas-bet-gimtojikalba- lietuviu-kaip-per-30-metu-pasikeite-tautiniu-mazumu-padetis-lietuvoje (in Lithuanian)

- Cvilikienė, J. (2020): ‘Gyvenimas prieš 30 metų: Kiek tuo metu kainavo televizorius ir kas uždirbdavo daugiausiai?’ [‘Life 30 years ago: how much did TV cost at the time and who made the most money?’, Swedbank Lietuva. Available at: https://blog.swedbank.lt/ pranesimai-spaudai-asmeniniai-finansai/gyvenimas-pries-30-metu-kiek-tuo-metu-kainavotelevizorius- ir-kas-uzdirbdavo-daugiausiai?fbclid=IwAR0jcfhobcyngvsLEVMhV_pfa9NwtwTLrJyw6CLUNcHCgT7NkxjhwtZsVY (in Lithuanian)

- Kasparavičius, G. (2021): ‘Olandas F. Erensas: 90-ųjų Kaunas buvo stebėtinai patrauklus (Nematyti kadrai)’ [‘Kaunas in the 90’s was surprisingly attractive’]. In: Kaunas Pilnas Kultūros, 18 May 2021. Available at: https://kaunaspilnas.lt/olandas-f-erensas-90-uju-kaunasbuvo- stebetinai-patrauklus-nematyti-kadrai/ (in Lithuanian).

- Lieven, A. (1995): ‘Pabaltijo revoliucija: Estija, Latvija, Lietuva – kelias į nepriklausomybę’ [‘The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania – the Road to Independence’], pp.357-364.